Some of the best advice that Olga Rosario received about teaching early learners is to never give up on a student. That means continuing to provide students with tools they need to master skills and meet goals.

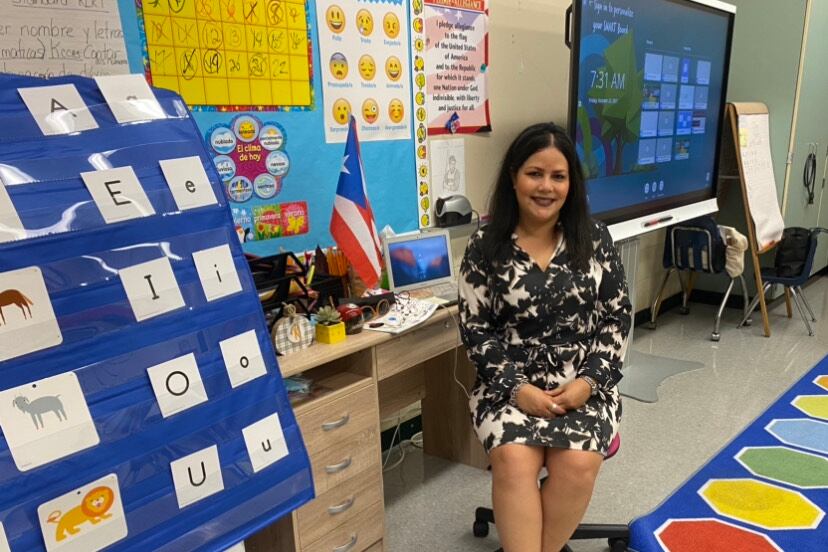

Rosario, is a dual-language kindergarten teacher at Lewis Elkin Elementary School in Kensington. This school year, she is closely observing the development of early learners who returned for in-person learning on Aug. 31.

The school serves more than 800 students in grades K-4, but its youngest learners are a particular concern this year, as kindergarten enrollment districtwide fell nearly 30% last school year compared to the year before. First grade numbers dipped, too.

Those numbers rebounded a bit for the 2021/2022 school year. As of late August, kindergarten registrations were up 27%. Data from the district show that kindergarten enrollment went up by about 1,100 students this year, but is still below pre-pandemic numbers and district projections.

This year, Rosario is focused on re-establishing classroom norms, routines and expectations. It’s a challenge. (So, too, is getting kindergartners to keep their masks on.)

“Due to the pandemic, many of my students did not attend preschool last year; therefore, kindergarten has been their first school experience, so children are learning how to behave and engage as students,” she said.

One of the most gratifying aspects of teaching is seeing a student’s face light up because they have accomplished a goal, Rosario told Chalkbeat, noting: “I have witnessed students’ progress throughout the years and it gives me great pleasure to see students blossom.”

Rosario spoke recently with Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What was the biggest misconception that you initially brought to teaching?

My teaching career started as a paraprofessional for students learning English at a charter school in Philadelphia. My focus was to teach English as a second language and to help students assimilate to a new culture. As a Spanish native speaker, my goal was to support English learners and provide tools for my students to succeed academically and to thrive in a new learning environment. I don’t recall having brought any misconceptions as I totally related with the student population.

How have you helped your students adjust to in-person learning this year?

I have created a plan of teaching that reinforces consistency and integrates clear norms and expectations in the classroom. I have accomplished this by inserting exercises that remind students of correct posture and positive behavior throughout the lessons. I am also supporting their academic learning by implementing interventions, such as one-on-one support and small group instruction.

Describe what makes your teaching experience unique.

I identify myself with my students, their families, and culture – and representation matters. As a Puerto Rican, I recognize my students’ needs, challenges, and wants. Establishing a relationship and an effective line of communication with my students and their parents promotes students’ trust and parents’ support.

Have you noticed any special challenges Latino students are facing now?

I strive to provide as much support and resources to my students’ families because I feel there is a correlation between language barrier and the lack of support from parents, as [parents] feel less confident to know how to help their student. At the same time, many parents are less involved as they feel overwhelmed by what they feel is their main contribution to their families — to work and ensure that the main necessities are provided for their families.

Why is it important for parents to monitor their children’s development? What should they look for?

It is extremely important for Latino parents to be involved in their children’s learning starting in their early years at school. The benefits are great for students, as it motivates them to do well and it strengthens the emotional skills as [parents and children] work together for a common goal. Parents can support their students with homework, reading, and with building of skills that they may see their students having difficulty learning. They can also be involved by [encouraging] opportunities for play, communication, and physical activities. As a teacher, I am able to recommend ways for our parents to be more involved in their children’s development.

Tell us about a memorable time — good or bad — when contact with a student’s family changed your perspective or approach.

A memorable moment that stands out is witnessing a student that developed during online learning. In the beginning of last academic year, the student was struggling in virtual school so I reached out to the parents to help me encourage their child. He slowly began to achieve goals. When we returned to in-person learning, he continued making progress. I could sense the desire to learn and that made a huge difference. I was pleased with how much the student blossomed by the end of the school year.