The importance of early childhood education has never been lost on Philadelphia, from its push for pre-kindergarten five years ago to its ongoing efforts to expand access in vulnerable communities.

But the pandemic has shone an even brighter spotlight on the need to prioritize high-quality instruction for the city’s youngest learners. After schools shuttered due to the coronavirus, the School District of Philadelphia saw its kindergarten enrollment drop sharply — about 30% compared to the previous year. That’s three times the national average. First grade enrollment also declined 8%.

Additionally, goals to expand pre-K to more students were hampered by the pandemic. The aim for PHLpreK was to fund slots for 6,500 students a year, but the effort is funded by the city’s beverage tax — the revenues from which declined about 15% during the pandemic.

This comes amid a backdrop of disappointing achievement and vast racial disparities in test scores. A report earlier this year found just 32% of third graders in Philadelphia read on grade level, with gaps among racial groups and low scores for students learning English and those with disabilities.

Educators find themselves grappling with teaching 5-year-olds who have had no formal educational experience and 6-year-olds who maybe have remained in preschool an extra year.

Chalkbeat is meeting this critical moment with a guide featuring stories explaining the state of play in early childhood in Philadelphia. Reporter Ann Schimke examines how behavioral issues that grew out of the pandemic are impacting efforts to limit suspension among early learners. Ann will also look at the likelihood of universal preschool coming to Philadelphia. Dale Mezzacappa writes about how one child care facility is facing the staffing shortages that are hampering centers nationwide. Samaria Bailey looks at the importance of parental involvement in early learning. And Johann Calhoun talked to an early childhood educator about introducing students to school for the first time this year.

Check out the stories in the guide below.

Preschool suspensions and expulsions have dropped in Pennsylvania. Here’s why that progress is in jeopardy.

Jane Stadnik regularly gets calls from Pennsylvania families whose young children are about to be suspended or expelled from preschool, often for things like throwing toys, pushing over furniture, or repeatedly running out of the classroom.

As a family resource specialist at the PEAL Center, a statewide advocacy group for children and youth with disabilities, her job is to help such families access therapy or other support so children can stay in their classrooms.

In Pennsylvania, as in many other states, preschool suspensions and expulsions in public schools have decreased in the last several years. Despite this trend, such removals still happen, and disparities based on race, gender and disability status persist. Some advocates fear the pandemic could stall or reverse recent gains.

Pennsylvania could get universal preschool. Here’s how.

More than half of Pennsylvania 3- and 4-year-olds don’t have access to public preschool programs. There simply aren’t enough slots, even with slow-but-steady state funding increases over the past several years.

Advocates say federal money will be key to creating a universal preschool program in Pennsylvania — one capable of reaching the state’s nearly 300,000 preschool-age children. Now, for the first time, that federal influx is a distinct possibility as lawmakers debate President Biden’s massive social spending bill, which includes billions for preschool nationwide.

“If something like Build Back Better goes through, that’s a lot more money that’s going to be available to serve a lot more kids.”

Child care staffing shortages across Pennsylvania persist, but solutions taking shape.

While staffing has always been an issue in the industry due to its persistently low pay and often stressful working conditions, shortages have never been as bad as they are now. During the pandemic, 255 of just over 1,000 total centers in the state permanently closed.

The state helped providers continue to pay staff for several months in 2020, but that didn’t last long. Many workers found that they could make more money working at Target or Walmart or Starbucks, among the companies that have raised wages in an effort to maintain their own staffing levels.

“It’s a hard job. Children are a lot of work, you have to have a big heart, a lot of empathy, a lot of patience. It’s a lot easier to hand out a cup of coffee.”

Parental involvement crucial for Philly’s early learners, advocates say.

With remote learning, many parents took on the role of part-time teacher to their children. Now, with most students attending full-time in-person school — some for the first time — some child advocates in Philadelphia say that parental support is more important than ever.

“Parent engagement helps create that safety net for children and that safety net includes making sure there is a space and opportunity to learn those skills at home.”

For many of her students, this year is their first school experience.

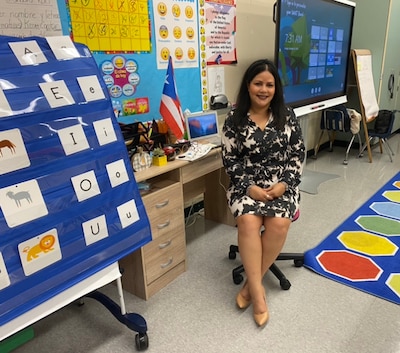

Olga Rosario, is a dual-language kindergarten teacher at Lewis Elkin Elementary School in Kensington. This school year, she is closely observing the development of early learners.

Rosario is focused on re-establishing classroom norms, routines and expectations. It’s a challenge. (So, too, is getting kindergartners to keep their masks on.)

“Due to the pandemic, many of my students did not attend preschool last year; therefore, kindergarten has been their first school experience, so children are learning how to behave and engage as students.”