Big cities across the nation, from Boston to New York to Chicago, have managed to hammer out differences between their school districts and teachers unions over the gradual reopening of schools.

In Philadelphia, not so much.

Here, school buildings have been closed for nearly a year. A mediation process between the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers and the district has dragged for weeks, delaying the district’s planned opening of schools for some prekindergarten through second grade students until March 1. Teachers refused to re-enter buildings on Feb. 8 to prepare, choosing to protest outside their schools instead.

On display is a long legacy of mistrust in the district’s administration, something that predates current superintendent William Hite but has intensified during his eight-year tenure. The school building stock is old and has a history of damning safety problems and deferred maintenance. Several years ago a teacher contracted mesothelioma, which is specifically related to asbestos exposure; in 2017 a first-grader got lead poisoning from eating paint chips that fell on his desk; a $40 million co-location project was so severely bungled that students from two schools had to travel elsewhere for an entire semester.

The district, operating in a state with among the nation’s biggest spending gaps between its rich and poor districts, has said it needs $4.5 billion to fully upgrade its buildings and billions more to catch up with delayed maintenance. Still, officials have long come under criticism for not being good stewards of the schools.

The union sees its moment to draw renewed attention to all the flaws, neglect, and history of mismanagement, hoping to compel the district to act more aggressively to fix buildings and perhaps shake loose additional funds to do it.

But others worry this impasse is coming at a big cost to Philadelphia students, most Black and Hispanic from low-income families, who they believe are being harmed the longer they stay out of school.

“People are trying to address historic conditions in a crisis without regard to whether those building conditions are [bad enough] in every case for children not to go back to school,” said Donna Cooper, executive director of Public Citizens for Children and Youth, one of 14 child advocacy organizations that issued a statement last week calling on teachers to return to buildings. She said Mayor Jim Kenney and some council members are “trying to lower the temperature so that people can have rational conversations.”

“We get it, the district has a bad record on buildings,” she said. “But they’re holding these kids hostage. They’re trying to get it all solved with this crisis.”

Several sources told Chalkbeat that the major sticking point in the negotiations is over adequate ventilation in classrooms. Ventilation has been an issue in other districts, but nowhere has it taken on the importance that it has in Philadelphia. It is looming larger than vaccinations for teachers, which are starting Monday after pressure on the city from both the union and the district to move school staff up the priority list with other essential workers.

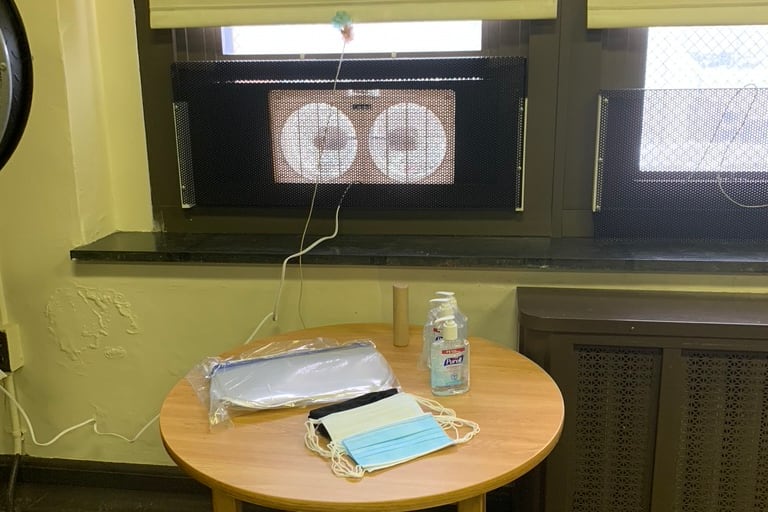

The focus of the uproar has been the district’s use of up to 3,000 small residential window fans to improve circulation in 32 schools where the ventilation systems are no longer operable.

In some of those schools, the ventilation systems were turned off because their components are contaminated with asbestos, a longstanding problem in city school buildings. Union officials want to know if asbestos has been removed from those systems — and say they aren’t getting answers.

“There is concern that there has been asbestos in air systems and they want to make sure those systems are remediated before being turned on,” said one person with knowledge of the mediation process who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the talks.

For their part, district officials believe they have been transparent and provided mountains of information, enough to establish that the district has made buildings safe for occupancy, especially since most experts don’t regard ventilation as the primary measure for keeping schools safe. They instead cite vigilant mask wearing, social distancing, and frequent COVID testing.

According to those with knowledge of the mediation process, the district has provided the union and the mediator reams of documents about each school. But the union says that is not enough.

“The district has turned over an immense amount of data, on air handling, ventilation type, square feet, how many people it is safe to have in each classroom,” said Deputy Mayor for Labor Rich Lazer. “The union is doing due diligence in making sure the information is accurate. It’s an immense process.”

He added, “Everyone’s goal is to open up schools safely.”

Hite has said that since schools closed in March due to the pandemic, the district has invested $65 million in COVID-specific enhancements and more than $250 million in building improvements, including removal of “hundreds of thousands of feet” of asbestos. But he has not been more specific about work in individual schools.

The superintendent has also expressed frustration at the lengthy mediation process and said he thinks Philadelphia has done more than other districts regarding ventilation and the public release of information, including school-by-school air balancing reports measuring circulation in hundreds of classrooms. He has also highlighted experts who favor reopening, such as those at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and national reports showing that schools are not major vectors of virus spread.

“Our collective focus must be on finding common ground so we can safely reopen schools for the thousands of families who want and need their children to return to in-person learning,” Hite said in a statement to Chalkbeat. He was unavailable to be interviewed.

All the other cities that have come to resolution over phased-in pandemic reopenings have had contentious labor-management relations. All of them have old buildings with a variety of ventilation systems that have suffered from deferred maintenance and age.

Yet, “In every other place, we came to an agreement,” said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, in an interview Friday. With the use of certified experts, “they’ve figured out what the proper ventilation fix would be to bring in enough fresh air, and they’ve done that work.” Chicago has made use of air purifiers, for instance, rather than “cheap” fans, she said. Some districts have used fans, but she said they were “fans appropriate for use” in school buildings.

“I do not know why Superintendent Hite is not rolling up his sleeves and trying to work with the union and parents in figuring out the ventilation issues in each school and making it work,” Weingarten said. Instead, “district lawyers are fighting tooth and nail against giving any real information to the community.”

Dripping with incredulity, she also brought up the district’s latest mishap — the revelation that some of the tape used to adhere the social distancing signs in schools contained lead and had to be removed.

In Philadelphia, she said, Hite “would rather say to the public things are safe to shield his staff’s own incompetence and at the same time be completely obstinate in the mediation ... It boggles my mind. I don’t know what’s happened to him.”

Some parent groups are siding with the union, saying they have been left out of meaningful decision-making.

“The continued standoff between the PFT and the school district is frustrating, but not because it is keeping school buildings closed. It is a striking illustration of what happens when plans are made without all stakeholders, including parents, the PFT, support staff, and students, at the table,” said Parents United for Public Education in an open letter to Hite.

The impasse was on full display at a six-hour city council hearing on Wednesday. PFT environmental scientist Jerry Roseman described in detail what the union was doing to verify the volume of information the district has provided. He and his team are conducting a meticulous, three-step analysis of 8,000 spaces in 152 schools, he said, with one step being “careful review of all relevant documents and data to ensure there were no asbestos issues or concerns associated with ventilation systems.”

And, he said, the district didn’t provide all the information requested until Feb. 14, more than a week after the mediation process began.

The union’s review, which Roseman said “is just getting underway,” has already identified “a number of serious problems” beyond the concern about asbestos. He ticked off window and exhaust fan issues, as well as a lack of basic information about the early-grade rooms, such as square footage and data about outside airflow.

He said as the review proceeds, the union is continuing to ask the district for more specific information — and is apparently not getting everything it wants.

Weingarten’s more blunt assessment, based on what she is hearing from Roseman and others, is that “the district has turned over tons of paper that says nothing.”

In his statement, Hite defended the district’s actions, saying it “has and continues to engage in the mediation process with PFT openly, honestly and with the urgency that this moment deserves. Any suggestion otherwise is just plain false. Our students, families and staff have been through so much already this past year. They deserve better than that.”

Caught in the middle of the drama is Mayor Kenney, a major ally of the PFT and also a supporter of Hite, who wants schools to open soon and is trying to ease both into some kind of agreement. Part of that effort included enlisting the sheet metal workers to install in schools “air pressurization boxes” that use ultraviolet light filters to kill pathogens. Weingarten said the district has not embraced the offer; Hite did not respond about it.

Council member Helen Gym, who co-chaired the hearing, emphasized that there could be “help on the way” in the form of both state and federal assistance to modernize school buildings. Two Philadelphia Democratic legislators announced Friday they are introducing bills to give $1 billion to school districts across Pennsylvania to fix “toxic schools,” which they note also exist in the state’s Republican-dominated aging steel towns and rural areas.

The district plans a hybrid reopening in which two cohorts of students each attend class twice a week, with Wednesday virtual for everyone as the schools are deep cleaned. This is the third try at this since September. Almost 30% of the 32,000 eligible students chose to attend in-person school.

Ventilation aside, the district has outlined a plan for keeping reopened schools safe that is more robust than some other large cities. There will be weekly testing of staff and random rapid testing of students. The city has also begun a vaccination program specifically for teachers and others who work in schools. Protocols are also in place for notifying parents immediately about positive cases, letting them know if their child was exposed, and closing the buildings if more than six cases within two weeks are identified. (This has been the protocol for more than a hundred private schools that have continued to operate in the city, and there have been just nine “outbreaks” requiring closure since September.)

At the council hearing, most teachers and parents who spoke questioned the district’s actions, repeating their conviction that they don’t think buildings are safe and displaying the deep distrust in the district’s leadership.

“What has become clear is that the school district doesn’t really care about children,” said parent Amy Henderson, whose child attends Meredith elementary, the school where the teacher was diagnosed with mesothelioma. Parents “had to fight” to get asbestos removed from the school, she said.

But she was immediately followed by parent Michael Gorman, who said that there must be movement for children to return to in-person schooling sooner rather than later.

“Virtual school is not school, it just isn’t,” said Gorman, whose daughter is a fifth grader at the Girard Academic Music Program elementary school in South Philadelphia. “Lessons don’t have the same impact. Kids, teachers and parents are burning out. The mental health challenges are staggering.”

More “privileged kids” in suburban and private schools “have been in school all year without expensive upgrades to ventilation … in Philadelphia, you can eat inside, gamble, go to the gym and go shopping, but public schools?”

“How does that reflect on our values.”