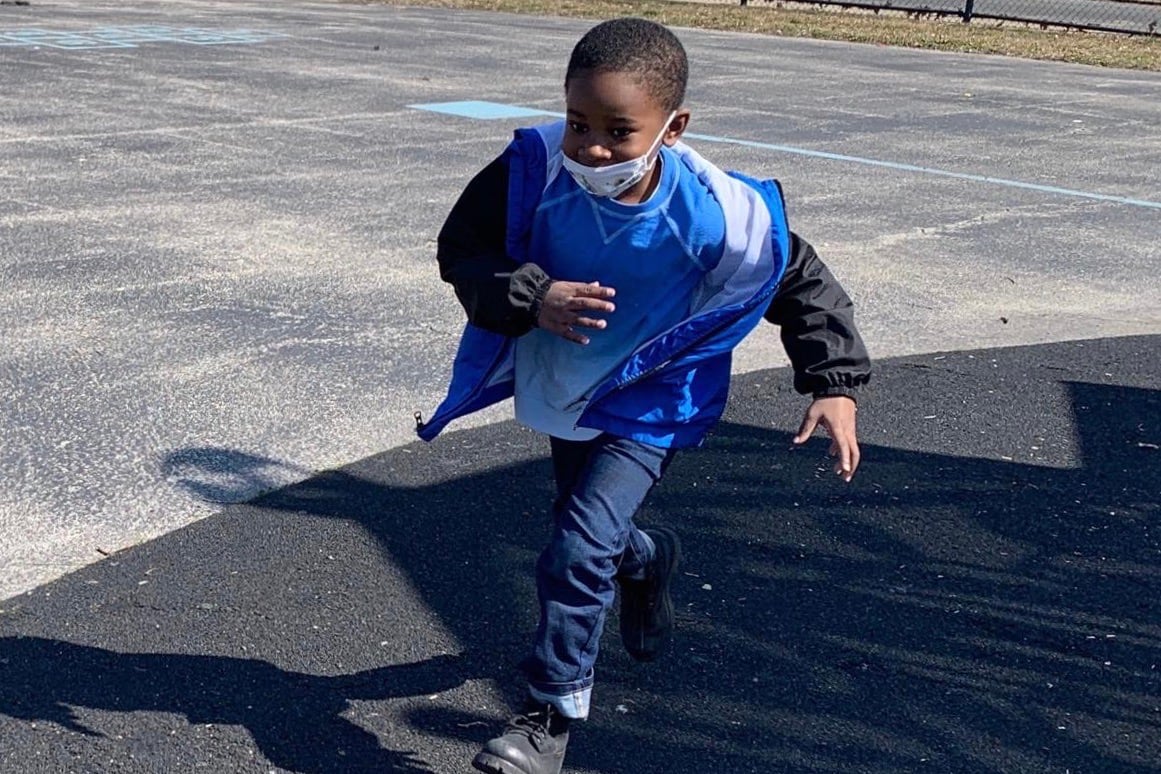

For a year of remote learning, Marjorie Boone made sure that each of the seven grandchildren living with her took a break from their virtual classes to go outside and play.

Not only was it a needed break for Boone and the children, but it was also the closest approximation of recess that she could provide within the context of their in-home virtual learning environment.

“I felt they needed fresh air to rejuvenate their mind - sometimes I let them go in the back and play for a little bit to refresh the mind as long as weather permitted. As the weather got cold, I still made them go out back to run just to refresh their mind because that’s what they make them do at school, so it seemed to work,” said Boone.

With the abrupt closure of schools in the spring of 2020, recess in Philadelphia’s public schools consisted of “time away from the screen” and “brain breaks,” according to the district. That’s not the kind of free play through which young students often learn problem-solving skills, socialization and teamwork. Now, as schools prepare to reopen for full-time, in-person instruction in the fall, some educators say that recess could be just as important as other subjects for early learners.

“Informal play is something that is critical to child development. We know from research that [they] need to have play that isn’t prescriptive, that we aren’t telling them what to do so they can break things and explore and skin their knees, so they can know ‘I shouldn’t do that again.’ Informal recess allows children in early childhood years to really understand the whole world around them,” said Amy Giddings, an associate professor and academic director of the master of science in sport business program at Temple University.

Boone’s granddaughter, fourth grader Brooklyn Mills, who attends Edmonds Elementary, said she missed recess when schools were closed. Although she had several other siblings to play with at home, she said it wasn’t the same.

“I felt really sad because I couldn’t run around with my friends. In my school [recess], I had all my friends to talk to and play around with. It was hard not to be in the school because you couldn’t talk to other people that you know,” she said.

Brooklyn had recess again after she returned for two days a week of in-person learning starting in March. “My teachers let me go outside because they thought it was a good idea and it was really sunny out,” she said.

Even before the pandemic, students in the city’s public schools weren’t guaranteed recess. A survey done by the School District of Philadelphia, conducted in 2018 and released in July 2019, found that 84% of the 51 elementary schools in its sample “were fully or partially” meeting a recommendation that students get 20 minutes of recess every day.

Other schools reported that students received fewer minutes per day or provided recess on some days but not all days.

Monica Lewis, a spokesperson for the school district, said that when schools started offering hybrid learning in the spring, in-person learners got some recess. She said the district has “not been made aware of any impact” that virtual learners had from not doing traditional recess.

In her work with a program that provides sports instruction to middle schoolers and some fourth graders, Giddings said she has observed the pandemic’s effects on play, including the “loss of interaction with peers” and the “informal element,” which she said can also be applied to the experience of early childhood learners.

“The pandemic has hurt that opportunity because they no longer have that opportunity for exploration with their peers. That really is a critical piece with childhood development. It’s even stronger with younger kids,” she said.

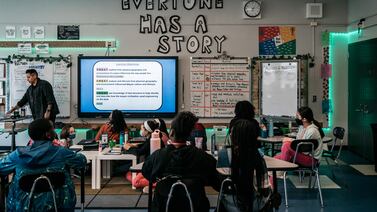

At Sheridan, an elementary school in Kensington, school leaders said recess was a pre-pandemic necessity for their students because of the lack of nearby green space and the prevalence of drugs and violence in the community.

“We saw that as a priority prior to the pandemic,” said Assistant Principal Julio Nuñez. “Our neighborhood kids lack access to green parks and recreation areas. The lack of access to green spaces is a big deal, so we see that as a need. When kids come in for socio-emotional learning, that recess takes the same level of importance as reading, math, social studies, science and all other subject areas.”

Nuñez said the school sees recess as an “oasis” for students.

Playworks, a national nonprofit with a local office in the city, served in 15 Philadelphia public schools this year to facilitate recess, in addition to providing digital resources to 150 elementary schools. Vice President of Field Operations Ivy Olesh said recess has looked different this year for students, and schools approached it in whatever way made the “most sense for them.”

When Sheridan started hybrid learning, a Playworks coach came in to lead recess. Nuñez said in-person students wore masks and followed social distancing guidelines, including avoiding games that required contact, and washing hands and using hand sanitizer before recess. Pre-recorded recess sessions were available for students who were not in person.

Nuñez said he does not know what the effects of an altered recess are for Sheridan’s students, most of whom are early childhood learners.

“Those executive functions of being able to be responsible for homework, those are the things you develop at school, being able to work with another individual who may have different views of you - that’s the part I think it’s too early to tell what the pandemic’s impact has been but at same time that’s going to be the priority for us - we know it’s impacted but we don’t know how far,” he said.

Local early childhood and health experts shared similar views.

“I would say it could affect their socialization skills, especially for young children who may have spent the end of pre-K and kindergarten in a computer setting, in terms knowing how to engage in face-to-face interaction,” said Tomea Sippio-Smith, K-12 education policy director for Public Citizens for Children and Youth, or PCCY.

“For many kids who have been learning only for the past couple of years, it may have affected their ability to interact with non-relatives or their ability to work as part of a larger group of students. Those are all possible impacts of students who were learning online. I don’t know of any studies off hand [but] one would expect that if you’ve never been in a setting and you’re a young student that has never had an opportunity to interact with other kids face to face, it will probably take an adjustment to learn those skills.”

Giddings agreed.

“Research shows the more opportunity children have for informal play, the greater they develop their creativity, their ability to problem solve, their ability to pay attention to details, so it really sets them up to be successful in school. It’s much more critical in the early ages than it is in middle school,” she said.

“It makes me so mad. I just feel for them. My recommendation for parents and educators would be to say it won’t be completely normal when kids go back, they won’t be completely normal. They could be nervous. I think we’re going to need to be really patient with these kids.”