Editor’s note: This article was updated to properly attribute material that appeared in a Johns Hopkins University press release and to remove language that appeared in a Temple News article.

Philadelphia Councilman Isaiah Thomas was a prolific reader as a kid.

Reading became routine for the councilman growing up in Northwest Philadelphia, mostly because his father was a teacher. It was also at Philadelphia Freedom Schools where Thomas enhanced his ability to read — noting authors such as Bob Moses, who wrote “Radical Equations” and Randall Robinson of “The Debt.” He read both books at Freedom Schools.

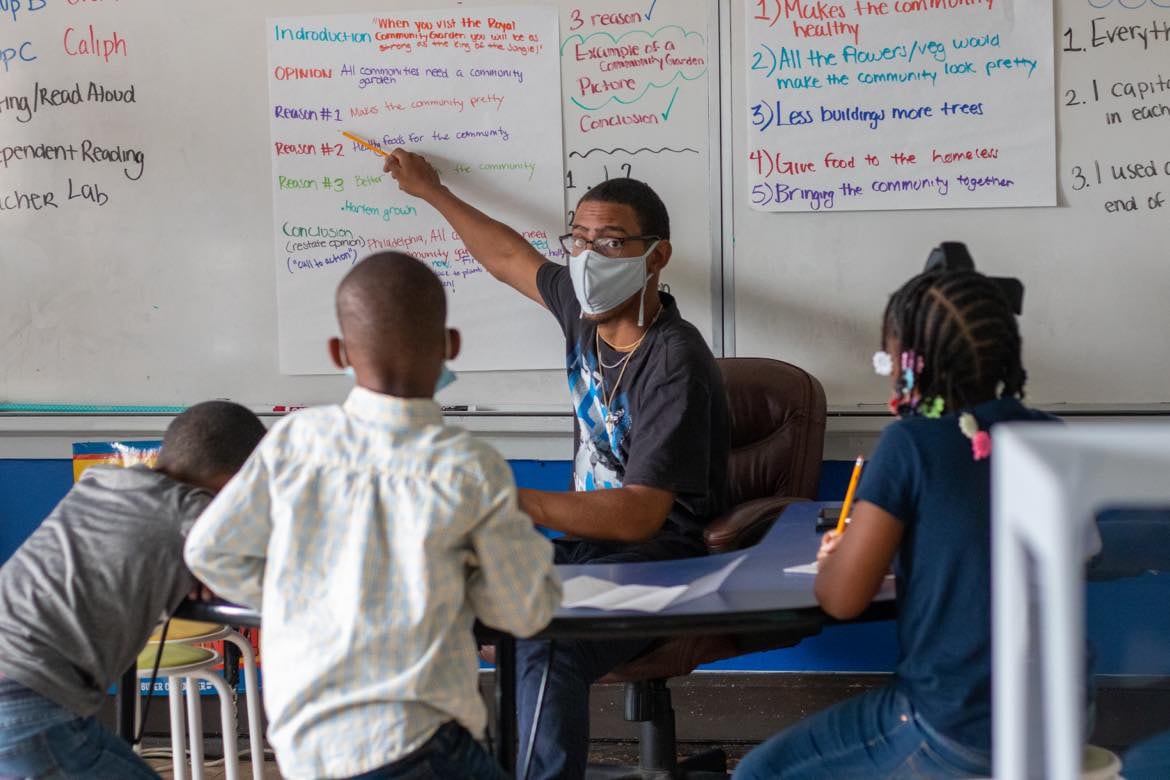

Thomas visited the Freedom Schools Literacy Academy, or FSLA, at Mastery Harrity Elementary School in West Philadelphia on Tuesday to engage with students on the importance of reading.

The councilman, who was a Freedom Schools student in the 1990s, believes the literacy program can be a model that could help the city with its youth literacy numbers — and its lack of Black teachers.

“When you’re talking about learning and content, the foundation of that is reading,” Thomas said. “It’s tough to be a good math student, if you don’t read; it’s tough to be a good science student, if you can’t read. So the foundation is reading.”

A report this year revealed only 32% of Philadelphia third graders read on grade level, a number that angered members of Philadelphia’s Board of Education.

“These trends are not surprising to any of us, now we have to talk about what we can do about it,” said school board member Mallory Fix-Lopez.

The report showed gaps among racial groups and low scores for students with disabilities and English language learners. It also showed that regardless of overall achievement at all schools, there were racial achievement gaps, with Black and Latino students scoring below whites and Asians.

Black and Latino students in the top-tier schools are on track to reach the goal of 62% proficiency by 2026, with about half reaching the mark now. But two-thirds of white and Asian students in those schools are already there.

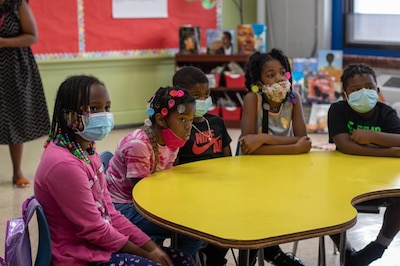

“We definitely find that about 60 to 70% of the students who come to our program are not reading on grade level,” said Erika Asikoye, director of FSLA. “We know that we’re going to get a range of children who just finished kindergarten, first grade or second grade who could benefit from our help.”

The literacy program focuses on “phonemic awareness, reading comprehension and positive racial identity” and spends a lot of time on letter sounds, Asikoye said . This awareness is a critical development skill for children and is linked to early reading success through its association with phonics.

In its success, the academy links reading with cultural awareness.

The Freedom Schools movement began during the civil rights movement and Freedom Summer of 1964. The original Freedom Schools were proposed by Charlie Cobb, a member of the Student Non-Violence Coordinating Committee (SNCC), to focus on literacy, positive racial identity, political education, and empowerment of Mississippi children who were suffering from “sharecropper” and “Jim Crow education.” SNCC recognized that the oppressive state of education in Mississippi was “geared to squash intellectual curiosity and different thinking” of Black children – the children and grandchildren of the adults SNCC was there to help.

SNCC leaders envisioned Freedom Schools as a model that could support Black children “to articulate their own desires, demands, and questions” and “to find alternative and ultimately new directions for action.”

In the late 1980s, civil rights attorney Marian Wright Edelman, who founded the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF), rebooted Freedom Schools through community-based organizations across the country. Philadelphia’s Freedom Schools can trace its roots to the CDF model.

Philadelphia Freedom Schools was founded in the 1990s by a coalition of Black educational leaders; Dr. Greg Carr, Erika Asikoye, and Dr. Ayesha Imani, who worked in the School District of Philadelphia, found support from David Hornbeck, former superintendent of the School District of Philadelphia. They would later form their own version of Freedom Schools, Philadelphia Freedom Schools (PFS), adding a high school component to bolster the inter-generational model.

Sharif El-Mekki, former teacher, principal, and founder of The Fellowship: Black Male Educators for Social Justice, draws much of his educational framework from his elementary school, Nidhamu Sasa, a small African Freedom School in the Germantown section of Philadelphia, started 50 years ago by Black activists and parents. His experiences at Nidhamu Sasa and in literacy classes as one of the many Black 4-year-old children who learned phonics on the indoor porch of his cousin, Dr. Suzette Abdul-Hakim of West Philadelphia, continue to inspire El-Mekki decades later.

These informed El-Mekki’s desire to use the Freedom Schools model to develop a national Black teacher pipeline – a model that provides Black high school and college students the opportunity to teach literacy and positive racial identity to first-third graders.

El-Mekki, founder of the Center for Black Educator Development, told Chalkbeat that using a community-based approach, one that involves an intergenerational model, adds capacity and strength in teaching youth how to read. It’s also linked to recruiting more Black teachers through the Black Teacher Pipeline.

“We need to double down on these efforts to use the science of reading and youth leadership to solve the complex issues that we face as a city and country,” El-Mekki said. “We’ll know we’re serious about the success of our future as a city when we hold ourselves accountable for the literacy rates of our youth. You can’t have a world class city without a highly literate citizenry - and all really does mean all.”

According to studies like those led by Constance Lindsey of the University of North Carolina, Black students do better when they have Black teachers.

A separate study from John Hopkins University found that Black students with at least one Black teacher are more likely to graduate high school and enroll in college, and if they have one Black teacher by the third grade, they are 13 % more likely to go to college. The percentage increases to 32% if they have two Black teachers.

“I think of literacy in terms of a human right - something that warrants our best efforts, investments and commitments,” El-Mekki said. “When we see countries that America loves to disparage, Cuba and Iran for example, but see how they prioritize literacy amongst their children and citizens we have to wonder, who actually has it backwards and is Third World?”

Though school board members vowed to make improvements to students’ reading skills, Thomas thinks the government should contribute in some form.

“Spend the money on programs that work,” Thomas said. “Even in the case of the school district, the federal government has allocated a significant amount of money to address the learning gap. So it’s up to the school district and the city to spend money on quality programs that do just that.”

Kristina Wilkerson, a parent of an academy student, said she’s pleased with the progress her son Dominic has made.

“Dominic loves to read. During the pandemic school year he would get off his regular school work to read books. So this program has helped to elevate that. He also gets to see teachers who look like him and says,. ‘Mom I can be whatever I want to be.’”