This story is featured in our 2022 Philadelphia Early Childhood Education Guide on efforts to improve outcomes for the city’s youngest learners. To keep up with early childhood education and Philadelphia’s public schools, sign up for our free weekly newsletter here.

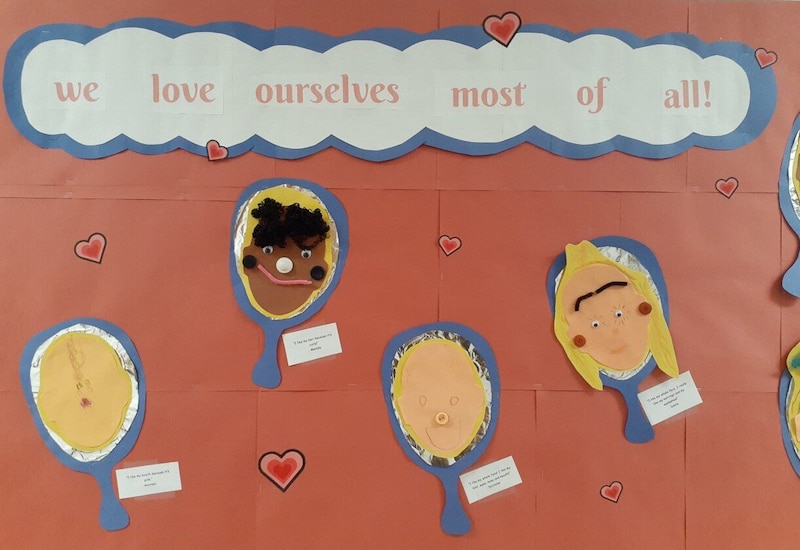

Inside Children’s Village, a 46-year-old nonprofit education center in Philadelphia’s Chinatown, preschoolers look into a mirror and create self portraits, then say which attributes they like best.

The game, called “Mirror, Mirror,” is a favorite of Sim Yi Loh, the family partnership coordinator at the center, whose families are largely first- or second-generation immigrants from East Asia.

“Children as young as six months can point out facial differences and skin color differences,” Loh said. “These activities we brought into the classrooms to boost self-confidence, and this will carry on into their learning.”

“Mirror, Mirror” is just one of several ways Children’s Village tries to embrace the culture, traditions, and customs of its early learners. And helping young children see themselves in the school setting can create a strong sense of belonging, some researchers say, that could help the early learners do better in school.

In classrooms throughout Philadelphia, educators and others seek to create such cultural ties. The city school district uses Relationships First, a community-building program for pre-K-12 students, to help them explore their identities and articulate what they value about their cultures.

Lessons that include prompts like asking kids to share pictures illustrating something about their culture they value, and reading books about what makes kids special or unique, are designed to spark questions and discussions about valuing identity and accepting others, a district spokeswoman said. The district recently partnered with the Children’s Literacy Initiative to help teachers identify and use anti-racist materials through an $84,000 grant that embeds coaches in classrooms.

“We understand that if students see themselves valued, reflected, and honored in books and learning experiences that we provide them, they’re more likely to learn,” Nyshawana Francis-Thompson, the deputy chief of the district’s Office of Curriculum and Instruction, said in a statement to Chalkbeat.

In 2019, the district adopted a “culturally and linguistically inclusive” curriculum designed to support teaching practices that reflect students’ experiences.

“We are constantly reviewing our curriculum and making adjustments to ensure that we are placing instructional resources and content in front of our students that will build their knowledge of themselves and other people through a culturally respective lens,” Francis-Thompson said.

Kids as young as 3 years old begin to sense that there may be a stigma attached to a particular social group or certain skin tones, hair textures, and body builds, and that’s the time for adults to to step in, said Gabriela Livas Stein, a professor and head of the psychology department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

“It’s important to be really purposeful in making them have a sense of pride in these different attributes,” she said.

Adults can help by giving specific, positive praise about features, saying things like, “I love your dark skin,” or, “Your hair is so gorgeous,” and exposing kids to books that reflect those statements, Livas Stein said.

Giving kids the “skillset” to handle unkind playground comments while retaining their “sense of optimism” can be tricky, Livas Stein said. “What we know, particularly from younger kids, is this happens a lot with their peers,” she said. “They’re all developing, so they may be saying things that hurt each other.”

There are online tools to help. Livas Stein recommends Sesame Street videos and the website embracerace.org. She added that positive messages about these issues to students — especially students of color — can lead to tangible benefits, such as increased motivation to do well academically.

Forging bonds, finding cultural role models

Grassroots programs that encourage cultural affinity are popping up around the country.

In Boston, a program called Love Your Magic aims to give girls of color a sense of belonging and the confidence they need.

Ivanna Solano, the program’s executive director, said she saw too many girls being told they were “sassy” or “disrespectful,” when “the reality was they were just advocating for themselves.” As a result, a disproportionate number of Black and brown girls are “pushed out” of schools for being disruptive, said Solano, a former teacher.

They’re also getting messages from the media and society in general that make them think they’re not important enough to share their thoughts in the classroom, she said.

It’s important to encourage a sense of belonging early on, Solano said. Adults often think young kids can’t talk about race or social justice at an early age, when in fact “students as young as kindergarten are noticing that,” she said.

Not all efforts to enhance students’ sense of belonging and cultural identity have to be in a strictly academic or school setting.

Love Your Magic offers retreats for girls as young as first grade to learn yoga, meditation, journaling, and other strategies to ease anxiety and improve well-being, Solano said. About 25 girls participated in a summer camp in New York State, she said.

At Children’s Village, which serves Chinese, Indonesian, Spanish-speaking, and other families from across the city, the food program is also multicultural. Kids may have tacos one day, chicken teriyaki the next, and curry the following day. Children often find comfort in the similarities of different cuisines, said Loh. They’ll often have bonding moments like, “Oh, you have rice too?” she said.

Of the 450 children who attend the Children’s Village preschool or one of its school-age programs, 60% come from non-English-speaking families, she said. And many Children’s Village families are first or second-generation immigrants from East Asia, Loh said.

In the name of assimilation, some parents want their children to speak only English, meaning they might lose the language their family speaks at home in the process.

“We say: It’s OK to embrace and keep the home language so you can continue to communicate with your child,” she said.

The center helps parents plan for their children’s education, helping them through an application process that can be stressful and complicated even for native Philadelphians, Loh said. The kids are also prepared socially and emotionally, as they’re taught skills such as how to make friends and how to pay attention, she said.

The nearby Chinatown Learning Center embraces a similar philosophy, encouraging preschoolers to learn English while retaining their Chinese language skills and cultural identity.

The preschool offers bilingual education and aims to prepare children and their parents for success in elementary school and beyond.

“They have teachers that look like them” and speak their language as well as English, said Carol Wong, the center’s director. “It is really important that they connect with, identify with, and have role models that look like them.”