This story is featured in Chalkbeat’s 2022 Philadelphia Early Childhood Education Guide on efforts to improve outcomes for the city’s youngest learners. To keep up with early childhood education and Philadelphia’s public schools, sign up for our free weekly newsletter here.

When teachers at Children’s Playhouse, a pair of child care centers in South Philadelphia, noticed children sneaking school-provided snacks into their book bags to take home, it was a “huge red flag,” said founder and CEO Damaris Alvarado-Rodriguez.

This practice typically happened near the end of the day, leading staffers to believe the children weren’t getting enough for dinner, or eating early enough, to keep them satisfied.

So the center asked families if they’d prefer their kids have an afternoon “supper” rather than a snack, and the answer was yes.

“Some families work long hours,” and between commuting and other responsibilities, children might not be fed until 8 p.m. or later, Alvarado-Rodriguez said. Other families, she added, just don’t have the resources to buy enough food.

The type of situation that unfolded at Children’s Playhouse is part of a broader pattern in the city, according to recent data about food insecurity, which the U.S. Department of Agriculture defines as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food.” Although the pandemic has drawn significant attention to the issue, it’s far from a new one.

Approximately 31% of Philadelphia’s children experienced food insecurity in 2020, up from just over 24% a year earlier, according to Philabundance, which operates food banks in the area as a member of the Feeding America program.

And almost half of principals in a 2020-2021 School District of Philadelphia survey said food insecurity was a “great” or “moderate” challenge. Black and Hispanic/Latino households had higher rates of food insecurity, as did families whose children were still learning English, the district found.

This level of food insecurity can have dire consequences for early learners, who need stability at home and in school settings to thrive.

Anna Johnson, an associate professor of psychology at Georgetown University who studies the link between food insecurity and the well-being of young children, said the issue can be linked to other stressors some face in early childhood.

“Children from low-income communities are more likely to experience food insecurity, housing instability, and neighborhood violence,” Johnson said. “It’s really a systemic problem. It’s hard for them to get the resources all kids need for a happy, healthy life.”

In food-insecure households, parents generally make sure the children are fed and go hungry themselves, she added. But such choices end up disrupting and straining parent-child relationships.

“Food insecurity impacts parents’ abilities to be those buffers to the stresses their children experience, which then comes out in what we’re calling child mental health,” Johnson said.

One tangible consequence of that increased stress is that anxious kids aren’t able to concentrate in educational settings, said Seth Pollak, a clinical psychologist with the Child Emotion Research Lab at the University of Wisconsin.

“There’s really good evidence that when children are feeling anxious, it’s really hard for them to listen to the teacher’s instructions or pay attention to the cues their peers are sending,” Pollak said.

By the same token, alleviating child hunger can go a long way toward setting kids up for success, researchers say. And some providers are searching for solutions.

Pennsylvania programs aim to ease hunger

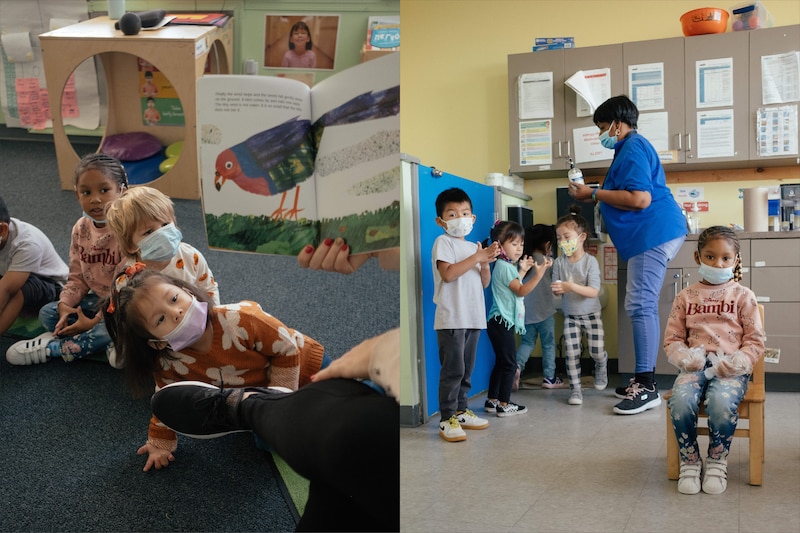

Children’s Playhouse works across different sectors in Philadelphia by providing breakfast, lunch, and dinner to some 278 children in Head Start, pre-kindergarten, and infant and toddler programs at its two centers. The center also has a social worker on staff to direct families to additional resources.

Children’s Playhouse also partners with Philadelphia to provide Head Start and city-sponsored preschool programs, and works with food bank operator Philabundance to provide meals to the community, Alvarado-Rodriguez said. She’s also started a nonprofit to expand food availability to the community.

Food insecurity isn’t confined to major urban areas. In rural Pennsylvania, the Power Packs Project provides families in 45 schools with ingredients and recipes for low-cost fresh meals.

The 17-year-old project works with schools in the cities of Lancaster and Lebanon to find families who qualify for free and reduced-price meals through school, and enroll them in the program. These families receive packs with a mixture of fresh and shelf-stable groceries and a recipe card.

The recipe is for a meal to feed four people, but the food in the box each week generally provides staples and ingredients for about 10 meals, said Brad Peterson, the project’s executive director.

“It’s all about reducing that meal gap,” Peterson said. “Our mission is to supply kids with food over the weekend so when they go back to school Monday, they’re well fed and ready to learn.”

With the help of Johnson and her Georgetown colleagues, Power Packs — which is looking to expand — has recently started looking into data like changes in test scores to measure the program’s impact, Peterson said. “We’ve really been more focused on short-term outcomes,” he said.

Children’s Playhouse hasn’t measured the success of its food program, Alvarado-Rodriguez said. “We’re working so fast we didn’t stop to collect data,” she said.

Demand for food programs is growing, and recent inflation is a “huge concern” for families, many of whom were struggling to begin with, Alvarado-Rodriguez said. And more broadly, COVID’s disruption of food and other benefits programs hurt families at the lower end of the socioeconomic ladder the most, Johsnon noted.

Children’s Village is working with state and local representatives to expand its food services, Alvarado-Rodriguez said.

“We have received testimonials throughout the pandemic,” and teachers have reported that the program has helped kids in their classrooms, she said.

Peterson attributed increased demand for Power Packs to the effects of inflation, but also to the elimination of federal benefits stemming from the pandemic. “We knew there was going to be a wave” of demand this year, he said. “A lot of the feeding programs that popped up during the pandemic have slowly gone away.”

One major change to longstanding nutrition policy during the pandemic was that schools provided free lunches to all students regardless of their household income levels during the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years. But those federally subsidized universal free meals ended this academic year.

On the other hand, Pennsylvania recently raised the income eligibility threshold for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to 200% of the federal poverty level, making more than 174,000 households eligible for the program. The expansion, which went into effect Oct. 1, “allows us to extend a reprieve to people who may be struggling” to pay for food, Executive Deputy Secretary for Human Services Andrew Barnes said in a September statement.

Philadelphia is also working to fill the gaps. In addition to providing regular meals in school and in after-school programs, the Philadelphia district works with Philabundance and the Giant Food-funded Share Food program to link schools with other resources, a district spokeswoman said.

Aside from such partnerships and official programs, teachers can also play a role on a smaller scale to alleviate children’s stress that’s related to food insecurity, said Pollak of the University of Wisconsin.

“Sometimes if a teacher can find some kind of quiet or stable thing to do” with a child who might be experiencing food insecurity or another form of instability at home, he said, it can make a significant difference. That could mean regularly pulling the child aside during lunch or recess and reading a story or having a snack, or even a group activity for a few children, Pollak said.

He hopes that the events of the last few years drive more research into (and attention to) food insecurity and the consequences it can have for young children. But for now, Alvarado-Rodriguez is driven not just by the need she sees, but by a moral imperative.

“It is disturbing that in parts of Pennsylvania, and Philadelphia, we still have families with children that are going hungry at night and they can’t afford to feed them,” Alvarado-Rodriguez said. “That is something that is unacceptable.”