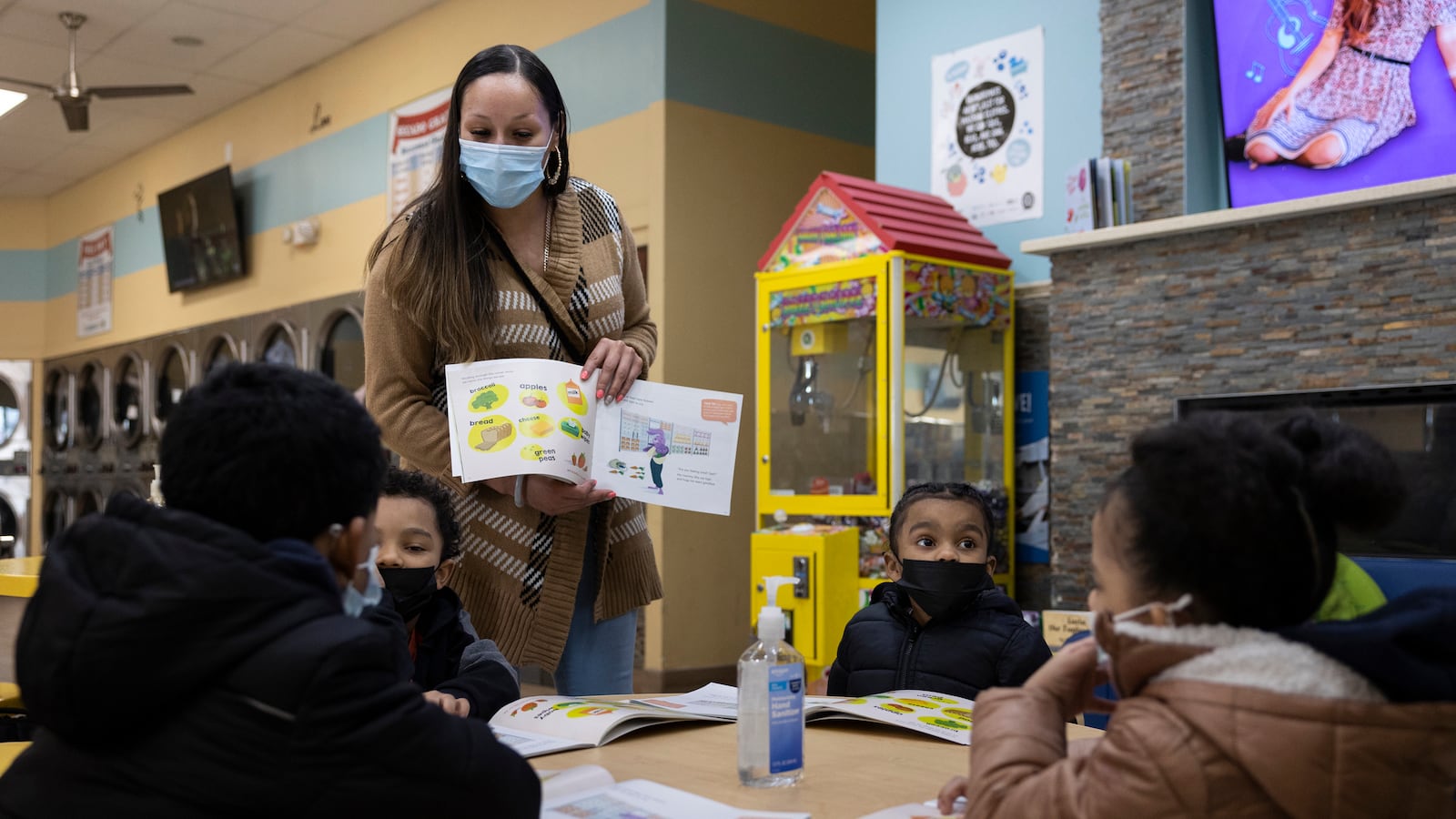

On a recent cold Saturday afternoon, Iris Hernandez and Carmen Colon were helping six Morales children through the letters, sounds, and words in the book “DJ’s Busy Day” about a bunny and his fun-filled adventures in ordinary places – the grocery store, on the bus, in his home.

“This is fun,” said Jeremiah Morales, 8, as he paged through the book, which is in both English and Spanish.

The group was ensconced in a cozy reading nook, with round yellow tables, child-sized chairs, and a fireplace, surrounded by colorful pictures and alphabet posters on the wall.

And washing machines. And dryers.

They were in a laundromat.

Hernandez and Colon are reading captains working with Global Citizen, which has been leading a community mobilization in partnership with the Philadelphia Public Library’s Read by 4th initiative, a citywide drive to help all children read proficiently by the end of third grade. Some research shows that early reading proficiency is linked to high school graduation.

The city still has a long way to go toward its goal. Before the pandemic, standardized tests showed that only about a third of children in district schools read at grade level by fourth grade.

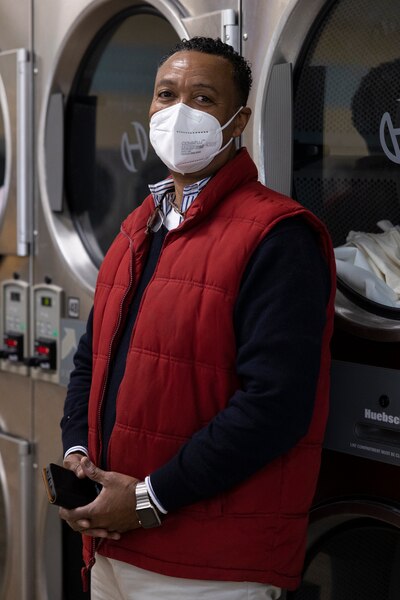

And the Laundry Cafe, at 4th St. and Allegheny Ave. in Kensington, one of four in Philadelphia owned by entrepreneur Brian Holland, has been enlisted in a nationwide effort to promote early literacy by harnessing the time that families, especially those in low-income neighborhoods, spend on workaday tasks.

Jenny Bogoni, the executive director of Read by 4th, said that she fears the already low rate of fourth graders reading at grade level has declined from its peak of 41% before the pandemic.

“We assume that the number has fallen,” she said. “I think the story here is that we are trying to physically transform everyday spaces in Philadelphia and families’ experience of raising a reader. To do that requires more than just changing teaching in the classroom, although that is critical. It’s doing things like this.”

Holland is from Chester, one of Pennsylvania’s poorest cities. He opened his laundromats after a long, successful career in the pharmaceutical industry.

For his “second act,” as he put it, he was looking for an interesting business opportunity that had the potential to have an impact on families in the kind of hardscrabble neighborhood that he grew up in.

And he landed on laundry. For many families, it is a weekly if not daily routine, with hours spent washing and drying their clothes in these community mainstays. Often, they bring their children with them, who either help out or must otherwise keep themselves occupied.

From the start, Holland worked to make the laundromat as welcoming as possible, with massage chairs and other amenities. He would give away diapers and men’s clothing to people in need, and occasionally hold seminars that helped people enroll in insurance programs.

He also put out a few children’s books, and he noticed that sometimes they would disappear. “I thought that was a good thing,” he said, “that the children wanted the books.”

He understood the impulse, and he wanted to do more. “I remember growing up, I had pride in my first book, it was mine,” he said. “The younger the better, the earlier you can get kids’ attention, the better off they are.”

Then, through the Coin Laundry Association, a nationwide industry group, he became aware of Too Small To Fail, an initiative of the Clinton Foundation that is focused on the well-being of young children.

The program was launched in 2015 with the realization that “more than half the kids in the country are unprepared for kindergarten, are lagging behind in critical language and literacy skills needed for school and for life,” said Jane Park, the director of Too Small To Fail.

At the same time, she said, since there were already a lot of organizations focused on early literacy by working with educators, the foundation looked for “a unique role we can play in supporting families.”

Children spend 80% of their waking hours outside school environments, so we “talked to parents, partners and others about the places they are going on a daily basis,” Park said. “The mission is to surround families with learning opportunities in the everyday places they go together.”

The laundromat was one. With willing participants like Holland, they went about thinking “how we could reimagine the space.”

They found out that, among other things, the typical laundromat had a lot of “no” signs around, a turnoff for children, she said.

“We talked to owners, we asked what their challenges are when it comes to kids and families in the stores,” said Park. They talked about “kids running around, slipping and falling, playing with laundry carts.”

So they created a “Family Read, Play & Learn” space with comfortable chairs and couches, tables, a box of manipulatives, and many books. The publisher Scholastic donated books, and KABOOM, a national organization concerned with playspace inequity, provides manipulatives and other materials and helped with design.

They festooned walls with posters in English and Spanish. “Let’s Use Our Imagination!” proclaims one poster that has pictures of animals in their natural habitats. Multicolored letters and numbers cover the sides of some washing machines, and a hopscotch grid is in one aisle. Small footprints on the floor urge children to explore.

The William Penn Foundation, which invests heavily in early literacy, helps underwrite the program. (William Penn is a funder of Chalkbeat.)

“We underestimate the power and potential of informal learning spaces, especially in environments where school systems have trouble getting resources,” Holland said.

In addition to creating a congenial space that encourages reading and other learning activities, once or twice a month, they also bring in reading captains from the citywide Read by 4th campaign, like Hernandez and Colon, for more formal activities.

Kyshia Roberto and Tyrece Morales are the parents of Jeremiah and his siblings, who range in age from 5-year-old twins to 12 years old.

“This is great for the kids,” said Roberto, who comes to the laundromat every week.

Margarita Davila was there with her daughter Aishah, 7, who was also sitting in the reading nook with her own book.

“This is pretty cool,” she said of the idea that her daughter, who attends Esperanza Cyber Charter School, could be encouraged to read even at the laundromat. “I never knew they had this.”

Colon, who works as a paraprofessional in several schools in the district, said she became a reading captain because she came to recognize the urgency of getting children to read early. “I’m a community person,” she said. “I could see how children became more engaged because of reading.”

Hernandez, who works with Philadelphia Virtual Academy, the district’s cyber school, agreed. She has four children who either graduated from or currently attend schools in the city. “It is so important for parents to be involved and do volunteer work,” she said.

Holland said he would host these events several times a week if families would come.

“You do as much as you can,” he said. “If you can help one kid in 10, you can change the slope of their lives. The goal is to have impact.”