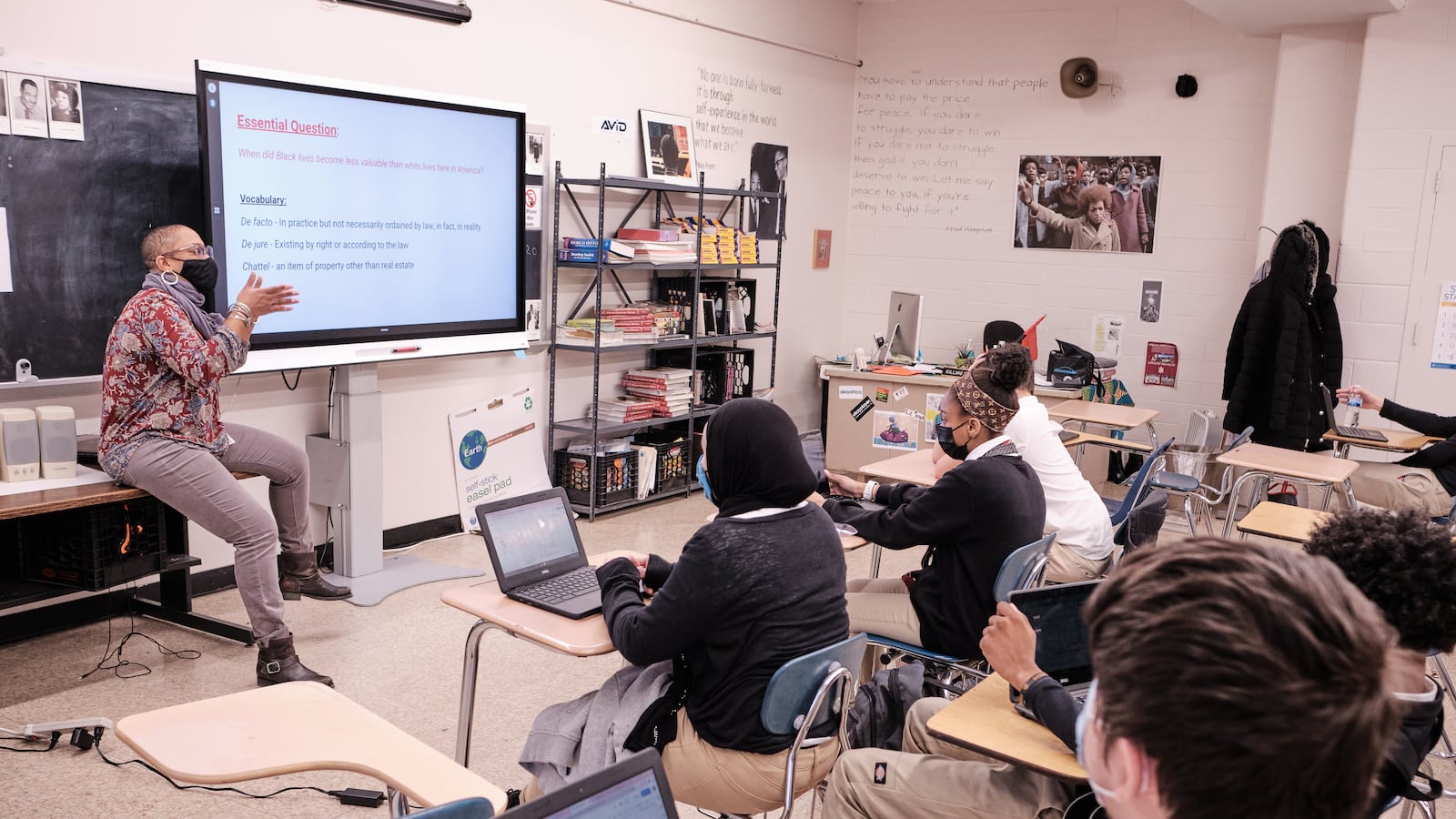

Students who walked into Stacy Hill’s classroom at Northeast High School one day last month for their African American history course saw this name on the white board: Amir Locke.

Locke was shot to death by police last month in Minneapolis after they entered his apartment using a no-knock warrant. It was Hill’s way of introducing the day’s essential question: “When did Black lives become less valuable than white lives here in America?”

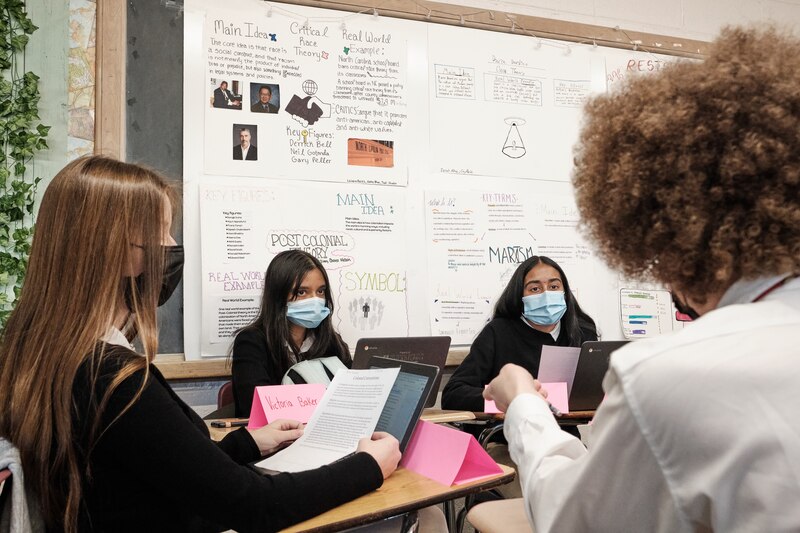

In another Northeast classroom later that day, students in Keziah Ridgeway’s class broke into groups to conduct discussions modeled after the 19th century Colored Conventions. At these meetings, held before and after the Civil War, Black leaders in the North and South organized in an effort to expand their rights.

Among the questions Ridgeway’s students considered: If you were alive during slavery, would you have supported a Black-led movement to go to Africa?

More than 15 years ago, Philadelphia became the first big city in the country to mandate an African American history course as a requirement for high school graduation. Now, at a time when dozens of states have adopted or debated laws to restrict teaching about race and racism, the city is embarking on a major initiative to revise and update the course Hill and Ridgeway are teaching, and also to infuse African American history and culture into the lower grades.

The effort stems from the Board of Education’s 2020 adoption of a set of “goals and guardrails” to guide its policy-making, one of which was to address and dismantle racist practices in a school district where the majority of students are Black and Latino.

Philadelphia “was leading the way before the political environment we’re existing in right now,” said Ismael Jimenez, the social studies curriculum specialist at the district who is directing the effort to revitalize the course. The plan is for the district to introduce the new curriculum next school year.

The district has not significantly changed the course, which is taught in the 10th grade, since introducing it in 2005. It uses a standard textbook that was last updated in 2011, and the course’s rigor, focus, and content have largely depended on individual teachers.

When Jimenez assumed his position a year ago, he said, “I recognized the gap from when the course was first implemented and where we’re at today.”

He has convened a group of veteran teachers to rethink the curriculum, and is investing in extensive, required professional development that includes a series of lectures and workshops that feature Africana studies luminaries like Bettina Love and Hasan Jeffries.

His aim is to make the course less dependent on a textbook and more reliant on primary sources. This would refocus the class on the “intellectual genealogy” of the African diaspora, Black resistance, and Black leadership in the United States, from Booker T. Washington to Malcolm X and beyond.

“Marcus Garvey read ‘Up from Slavery’ and was inspired to start the Universal Improvement Association, which Malcolm X’s parents belonged to,” Jimenez said.

And he wants to talk about these concepts “in an authentic way, not just as a procession of individuals.”

“We want students to understand how ideas of race were developed differently throughout the world depending on the orientation of European enslavers’ shifting definitions based on the size of enslaved African populations,” he said.

‘More than just a few names’

In the nearly two years since George Floyd was killed by a police officer in Minneapolis, racial justice movements have demanded more attention to African American history and culture in schools.

But a fierce backlash has developed as well, including in the Philadelphia region, in the form of a push to ban critical race theory from the K-12 curriculum, though it is not typically taught below the college level. An academic framework that studies how politics and the law perpetuate systemic racism, CRT has become a catch-all for conservatives who oppose equity initiatives and, in some cases, any teaching about race, bias, and racism.

Thirty-six states, including Pennsylvania, have introduced legislation that aims to restrict what can be taught about racism and bias. Pennsylvania’s bill along these lines, HB 1532, has languished in the House Education Committee without action for nearly a year.

In Philadelphia, educators think the course and the issues it deals with remain as crucial as they were in 2005, when the School Reform Commission adopted the mandate.

“What we wanted to do is highlight the fact that African American history is an integral part of world and U.S. history,” said Sandra Dungee Glenn, the School Reform Commission chair when the district made the course mandatory. “African American history is more than just a few names.”

Jimenez has an ambitious goal to make African American history “a centerpiece of what the district is doing” by 2025, the 20th anniversary of the mandate, and not only through one course, but by infusing its sensibility throughout the K-12 experience.

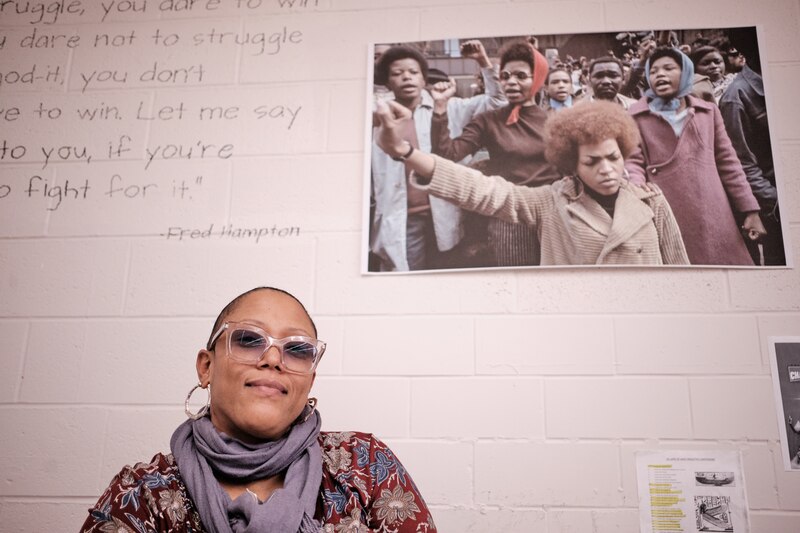

Jimenez taught the course himself for more than a decade at Germantown High School, which is now closed, and at Kensington Creative and Performing Arts High School. Both he and Ridgeway have been active in the Racial Justice Organizing Committee and the Melanated Educators Collective, which are groups that consist of educators and campaign for antiracist policies.

With the board’s new commitment to antiracism through its “goals and guardrails” initiative, teachers in those groups are helping to lead the movement rather than agitating from the outside.

“I didn’t get a lot of Black history in school,” said Ridgeway, who graduated from Girls High School in 2003. “We learned the usual ‘Christopher Columbus was a great person’” version of America’s founding and development focused on white men, she said. What Ridgeway, who is Black, gleaned about African American history came from books her father gave her and from TV shows like “Roots.”

Jimenez said that the course sheds light on the role of oppression in all human societies. “It benefits whites, Latino, Asian students to understand the deeper and larger history of African Americans” in this country.”

Like Philadelphia’s teaching force in general, most of those teaching African American history are white. They are also cognizant of how this might affect their approach to the topic.

”I’m open and honest with students that there’s a lot of things I can teach them and a lot I can’t,” said Nicholaus Bernadini, a social studies teacher at Samuel Fels High School who is white. “Like being Black growing up in the U.S.”

Adam Sanchez, who is also white and teaches African American history at Central High School, said he approaches the course “as trying to figure out what our society is. We still live in an incredibly racist society, and how do we deal with that?

“There’s a mythology that the civil rights movement was just in the 1950s to 1970s,” he said. “The struggle starts on the coast of Africa.”

Both Bernadini and Sanchez are on the team Jimenez assembled to update the course.

Bernadini said he starts his teaching by highlighting what happened on Nov. 17, 1967, when hundreds of Philadelphia students marched from their schools to the Board of Education headquarters. They were demanding more teaching of African American history, among other changes.

As Mark Shedd, the superintendent at the time, spoke to a delegation of students inside the building, police assaulted those who remained outside, on the orders of former police Commissioner Frank Rizzo.

That protest “leads to the African American history curriculum being developed in the first place,” Bernadini said. “It’s an empowering story.” A historical marker commemorating that event will be unveiled on March 19 at the former district headquarters at 21st Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

Awareness should start early

Not all teachers have been content to wait for the district to revamp the course and expand its influence. Karen Williams, the literacy coach at Muñoz-Marin Elementary School in Kensington, said she is “on a mission” to bring African American history to all city students from the earliest grades.

Like Ridgeway and Jimenez, she is active in the city teachers union’s racial justice caucuses, and also grew up in the city and attended its public schools.

“We studied Martin Luther King and learned about Rosa Parks,” she said. “That was pretty much it.”

At Muñoz-Marin, she has created a framework for students to study race and racism. Starting in prekindergarten and kindergarten, students focus on the meaning of “difference.” Older students study topics like identity, empathy, and inclusion.

“We want to really embrace the idea of diversity,” she said. “We use our differences to learn from each other.”

Shanay Anderson-Nixon, a tenth grader at Dobbins High School in North Philadelphia, is in John Winters’ African-American history section. She said she appreciates the course, but adds: “Why am I learning about all this now? Why is it just one year?” In her majority Black elementary and middle schools, she said, “We didn’t touch on it. I had to wait until 10th grade for a Black teacher who cared about what Black people did.”

To explore the answer to the question she posed at the beginning of her class about the value of Black lives, Stacy Hill at Northeast High School reviewed the treatment of Black people brought to America in the 1600s, before America became a nation or had an established legal system. The devaluing of Black lives began then, she said.

Her featured vocabulary word that day was “chattel,” which means an item of property, as in “chattel slavery.”

“The story of the African American struggle is a story against oppression and the resilience of oppressed people,” she said. Oppression due to ethnicity or racial characteristics occurs, she said, “in every culture and every piece of land on the earth.”

The students at Northeast come from backgrounds that reach across the globe, from China and Iran to Ukraine. Students in Hill’s class expressed enthusiasm for the African American history course.

“It changes your perspective on many things,” said Ayham Muhanna, a Palestinian student. “You learn what people have been through and how rough it was before and how history hasn’t really changed that much.”

“African American history is my favorite course,” said classmate Mayaser Omar, who is also Palestinian. “And the most important one.”