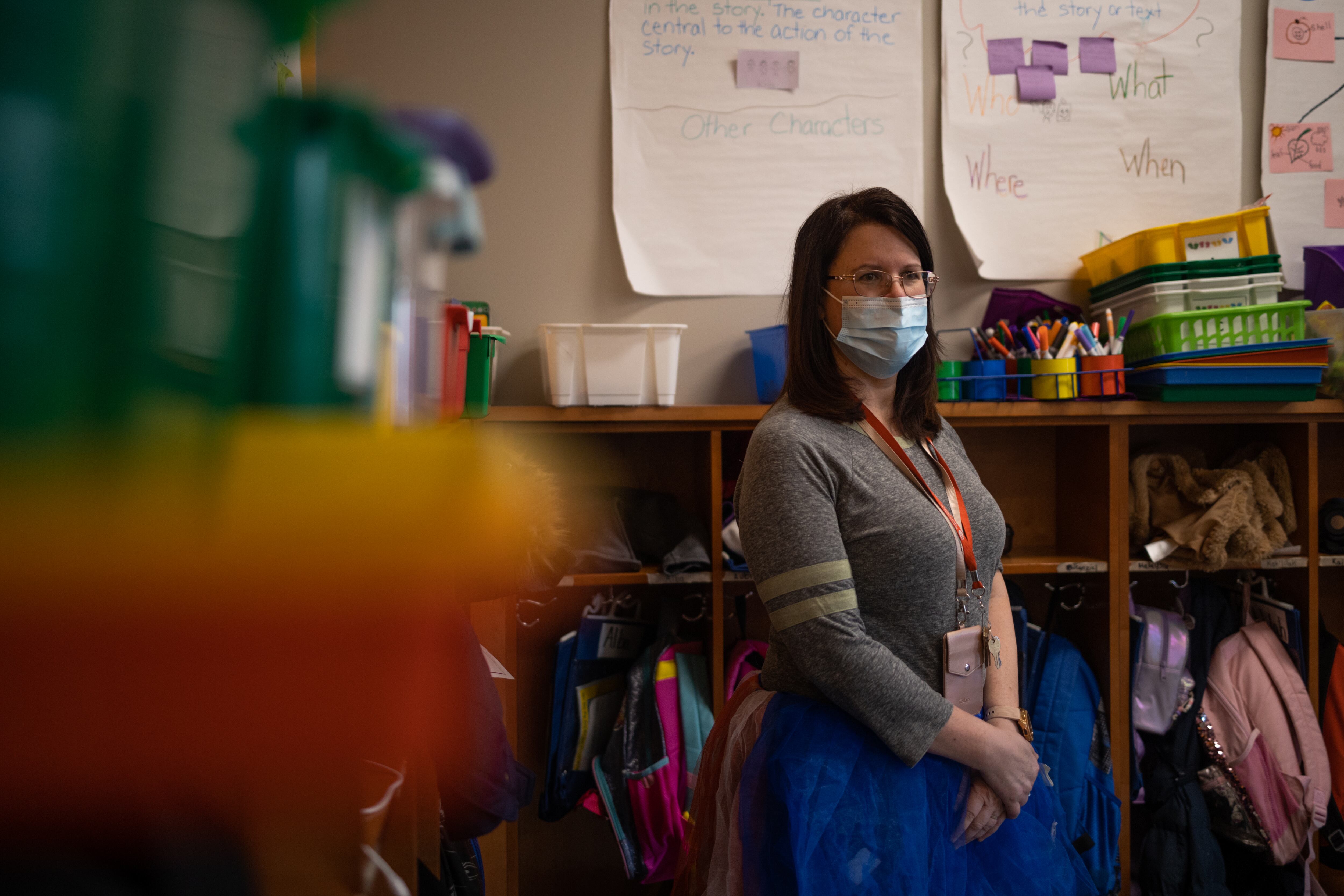

Philadelphia public school students and staffers will have to mask up for the first 10 days of the school year as a “precaution” aimed at avoiding widespread COVID outbreaks, said Kendra McDow, the district’s medical officer.

In a detailed justification of the district’s mask and other virus policies, McDow said the district decided on its course of action policy because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends masking for 10 days after exposure to the virus or a positive test, she said. Masks will also be required for 10 days after extended breaks.

Officials considered testing as an alternative to masking, but decided to go with masks as an intervention that could be implemented more rapidly than complicated testing requirements, McDow told Chalkbeat.

“The focus of our district is to keep kids in school, and we want to make sure there are very limited disruptions this first month of school,” McDow said. “We know kids are coming from being out, at summer camp, with friends and family, with multigenerational family gatherings taking place. The first day of school they’ll be transitioning to being indoors, in close quarters and in tight quarters.”

Philadelphia, which shared its school masking and other COVID policies with the public earlier this month, looks increasingly like an outlier: Most school districts around the country have loosened mask requirements for the coming school year. Some have criticized the district for the mandate and have questioned the science behind it, but others believe it’s a safe and rational response to the virus.

The district is stepping up efforts to share information about its decisions and provide information to parents. In a recent webinar for parents, for example, district procurement manager Christopher Holt said the district has supplies of three-ply masks for adults and children, as well as N-95 masks, which will be required for anyone returning to school after a bout with COVID.

And Shannon Smith, director of nursing for the district, encouraged parents to consult school nurses if they have questions about masking.

Testing will be available in schools during outbreaks and for symptomatic students, and the district will provide students with test kits.

While the Centers for Disease Control puts Philadelphia at a “medium” level for COVID transmission, the level could in fact be higher, McDow said. A decrease in testing and an increased reliance on unreported, over-the-counter tests means there could be asymptomatic or mild cases or exposures that aren’t being counted, she said.

Moreover, COVID outbreaks tend to rise around holiday or vacation periods, she said.

Federally funded Head Start and preschool programs will require masks for all teachers and staff. Tracey Petty, school health services coordinator for the district’s prekindergarten programs, said that to be consistent, state-funded programs in Philadelphia schools will follow that mandate as well.

Despite the opposition from some quarters, McDow said research has shown that masks work, and that the chances of transmission are higher around holiday periods.

She pointed to a 2022 study that found school districts with universal mask policies had lower levels of transmission than those in which masks were optional. And data from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia PolicyLab found increased COVID positivity rates around the 2021 holidays, she said.

Philadelphia is a diverse district in a large urban center, and “we really need to take into account the varying health conditions and needs of our students and staff,” McDow said. A high percentage of students in the district are obese or have other medical conditions that could put them at increased risk for severe complications from COVID, she said.

The policies and the mindset behind them are oriented around a major goal, McDow said: “We really are focused on keeping children in school so they can get in-person learning.”

‘Holding their feet to the fire’ on COVID rules

There are disparate views in the district about the wisdom of the new policies, particularly when it comes to masks, and how long they’ll last.

“We’re about to put 30-plus kids in a classroom and they haven’t been around each other,” said Trina Dean, an executive board member of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers and academic coach in the district. “I think masking for the first 10 days is just safer.”

In a statement, PFT President Jerry Jordan said the 10-day mandate was a “very brief period of masking” that would have a positive long-term impact. He said he was “cautiously optimistic” that following the first 10 days of school, further mandates won’t be necessary.

But Rahul Ganesan, who has a child entering kindergarten at the William M. Meredith K-8 school and another starting fifth grade at the Julia Reynolds Masterman Laboratory and Demonstration School, said he’s concerned that the mask requirement will pop up again during the year, and that the district won’t rely on sound metrics for determining infection levels.

Ganesan said he’s “hopeful” the district will listen to parents and take changing conditions into account as the school year progresses.

“People have to keep questioning and holding their feet to the fire a little bit,” said Ganesan, who framed the policy as an “equity issue” holding Philadelphia students to a separate standard from their peers in other districts.

Not all parents oppose the masking plan.

“COVID is still a threat, and I’d rather err on the side of caution,” said Catherine Collins, the parent of a Masterman senior.

“I think the lack of adequate ventilation and the poor condition of Philly’s public schools is a much bigger health threat,” Collins also said. “Our government’s COVID response has brought to light what many public school parents and staff have suspected for a long time: These buildings are unsafe for our children and for anyone required to work in them.”