When Philadelphia teacher Jane Fitzgerald learned about the death of her student Kahlief Myrick eighteen months ago, she performed a ritual that has grown far too familiar.

Fitzgerald took out a pen and added his name to a list of South Philadelphia High School students killed by gun violence or stabbed to death. At the age of 16, Kahlief joined about 50 other names on the list covering Fitzgerald’s two decades at the school, an expanding memorial to the crisis in the city.

“I actually wrote all their names down one day, because I was like, oh my God, I think I’ll forget,” said Fitzgerald, a special education compliance monitor and history teacher. “But I haven’t.”

With classes set to start Aug. 29, many school communities are carrying the excruciating burden of losing students who have fallen victim to gun violence in the city and haven’t made it to the new school year, graduation ceremonies, and other milestones.

Kahlief, a junior at South Philadelphia High (also known as Southern) at the time of his death, was set to graduate this past spring. Those who knew him well say Kahlief’s kind disposition, gregarious personality, and infectious laugh gave his 5-foot-4-inch frame a larger than life presence.

“He was engaging and loved to be around people, even when he got to high school,” Brittany Brunson, his mother, said. “His death doesn’t make sense.”

Kahlief died a few hours before the start of the school day, several miles from Southern’s campus at Broad and Snyder.

Concerns about Philadelphia’s gun violence long predate the pandemic. But since early 2020, children’s social isolation and their families’ economic struggles have merged with illegal gun sales to further destabilize public safety. Last year, there were a record number of homicides in Philadelphia. And what has emerged from the hundreds of shootings this year is a grim and heartbreaking statistic: Gun violence is currently the leading cause of death for children over the age of 15 in Philadelphia.

Like gun violence, the safety of children in school frequently generates headlines and divisive political debates. But Kahlief’s death underscores that whatever protocols, technology, and de-escalation tactics schools turn to, educators and parents are often powerless to shield children when they are going about their normal routines in their communities before and after school hours.

The violence leaves school communities reeling from shock and pain, over and over again. Each time a student like Kahlief dies, students and teachers are asked to recover with tools that don’t necessarily feel like enough. And COVID’s disruption of normal school routines has even warped the way in which people experience the shock and pain of losing students like Kahlief.

Fitzgerald was working virtually on the day another teacher told her about Kahlief’s death. “I was sitting at my computer and I just started crying like a baby. My husband came in and he’s like, what happened?” she recalled. “I told him another one of my students was killed.”

Those who knew Kahlief say he got good grades, never got into trouble at school, and had already started to turn his dream of being an entrepreneur into reality.

“Kahlief wasn’t into the street stuff,” Fitzgerald said. “When you picture him, you always picture him laughing and the people around him laughing. If another student was unhappy, or just going through something, he would communicate with them. That’s what we lost in Kahlief.”

A kid from South Philly with dreams

Roughly two years before Kahlief’s death, Grammy-award winning rapper Wyclef Jean joined VH1’s Save The Music Foundation to present Southern with a music technology grant in the school’s auditorium.

A guest host representing VH1 walked into the auditorium and started to get the students, who would get to see Jean perform, hyped up for the school’s grant. For some reason, the host singled Kahlief out of the crowd and brought the then-freshman onto the stage to perform for his classmates.

Kahlief proceeded to surprise and delight everyone with his rapping ability.

“He was clean, perfect, vibrant, and an absolute entertainer,” Fitzgerald said. “I filmed it with my phone, because it just captured him at his best. Just so engaged in the world and in life.”

Kahlief’s mother wasn’t surprised at all that he was picked out of the sea of students that way and wowed the crowd. Kahlief had a big personality and sense of humor that would draw people to him.

“He loved music and wanted to be a rapper. I mean, you may want to say he was a free spirit,” Brunson said. “Kahlief just wanted to learn about life, but he wanted to learn it through art.”

He later became known by friends by his rap name Fat Lief, or Lief.

Kahlief wasn’t solely interested in seizing the spotlight spontaneously. In 2018, he had a vision of using his business sense and artistic eye to open his own clothing line. To support his idea, Brunson bought Kahlief a pressing machine and a printer to create designs at home.

Just one year later — working with his brother Kaheir and a cousin — Kahlief was selling the apparel to friends and reinvesting his revenue to purchase more supplies.

He then stepped up his work by beginning to operate out of a professional print shop, where he was allowed to print his own designs on apparel.

Kahlief named the clothing line Immortal Never Die “because he wanted it to always be around,” Brunson said.

Outside of his own pursuits, Kahlief was also a leader in his family. The oldest of four children, his younger brother Kaheir was Kahlief’s best friend. He also had two sisters, Kamorah and Khodi.

He loved his siblings and took on the role of big brother through his actions, not just his age. When his mother and stepfather weren’t home, Kahlief fed his siblings and made sure they completed their homework before bed.

His grandmother Crystal Boyce, who along with his grandfather Norman Boyce helped raise Kahlief and his siblings when they were young, recalled that Kahlief was “so particular” about being an important part of his family as he grew older.

For his entire life, Kahlief was, as his mother described him, “chunky.” While other children might be paralyzed by self-consciousness about being heavyset, Kahlief — who was also shorter than his three siblings — had a different mindset.

Joe Gaines, the clinical coordinator for the STEP program at Southern that provides counseling services and support for students with behavioral or mental health needs, recalled that while Kahlief was not in the program, “I worked closely with a few of his close friends. Kahlief was always in the room and was drawn to help other students.”

“Kahlief loved hard,” said Antonio Anderson, a school climate manager at Southern. “His big thing was he needed to feel how he made others feel. And that was a big disappointment for him, when he didn’t get the love back that he always gave out.”

He also didn’t let his physical stature deter him from playing basketball and other physical activities.

“Even with him being heavier, he didn’t let that stop him,” Brunson said. “He didn’t let that get in the way of what he wanted to do.”

‘You really got to be safe out there’

Although Kahlief generally had a positive and outgoing attitude, a series of tragic and troubling events began to weigh on him.

In 2017, when Kahlief was in the seventh grade, one of his favorite uncles, Kamal Myrick, was gunned down about a block from Kahlief’s house. Brunson said his uncle’s death didn’t just traumatize Kahlief, but started to change how Kahlief viewed his environment.

In 2020, Kahlief’s stepfather Kahlif died of cancer. That same year, one of his friends was murdered.

Then there was a chance encounter on a train, one that highlighted the difficulties he had previously faced at school.

Brunson recalled her son telling her that one day, as he was riding the Broad Street line, Kahlief was approached on the train by two of his classmates from middle school. They confronted Kahlief and reminded him about the days when they used to bully him.

Normally, Kahlief did not back down in such situations. But this time, Kahlief stepped away and headed to the train’s exit when he reached his stop.

When Kahlief turned around to see where the two boys were, one of them pulled up his shirt to show Kahlief he had a gun. That image shook Kahlief.

Around the time of that meeting on the Broad Street line, Kahlief’s mother also noticed a change in his demeanor. He became more guarded and less jovial.

“He became a product of his environment by what he was experiencing,” Brunson said. “I believe he started channeling the possibility of death at 16 years old. I believe losing the number of people who were close to him hardened him and made him a bit cold.”

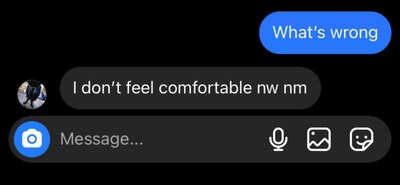

Two months before he was killed, Kahlief sent a text to one of his closest friends, Deagejah Comer, whom he had known since kindergarten. The text to Comer read:

“I don’t feel comfortable nw nm.”

The two abbreviations stood for “nowhere” and “no more.”

“I told him you really got to be safe out there, because if something happens to you I don’t know what I’m going to do,” Comer said.

“When you picture him, you always picture him laughing and the people around him laughing. If another student was unhappy, or just going through something, he would communicate with them. That’s what we lost in Kahlief.”

To her, what Kahlief experienced demonstrates that a focus on “beef or street beef” and coming out on top in those confrontations can lead some young people in the Black community to live ruthlessly through guns, while others live in fear.

But despite the hardships he faced, Kahlief did not abandon his desire to learn about the world.

In the last few months of his life, Kahlief became curious about religion. Though his family members are Jehovah’s Witnesses, Kahlief had considered converting to Islam after talking to a friend.

“I let him engage, but the one thing I wanted him to do was to read and learn and not just devote himself to something without knowing what he was getting himself into,” Brunson said. “He never got the chance to do that.”

An early riser’s trip to the store ends in tragedy

When possible, Kahlief liked to nap during daylight hours, meaning that sometimes he woke up before dawn.

At 4 a.m. on Feb. 18, 2021, Kahlief walked into a 7-Eleven on 70th Street in Southwest Philadelphia. He and a cousin were in the neighborhood visiting a relative, according to his grandparents, Norman and Crystal Boyce.

While in the convenience store, Kahlief had a short encounter with a much older man, according to Kahlief’s cousin.

“What are you looking at?” the man reportedly asked Kahlief, who retorted by asking the man the same question.

Shortly afterwards, the man left the 7-Eleven, but waited outside for Kahlief to exit. When Kahlief left the store, the man shot him, a police report about the incident stated.

Kahlief lay on the ground in a pool of blood in freezing weather. Police arrived at the scene before an ambulance, and drove him in the back of a car to Penn Presbyterian Medical Center in West Philadelphia.

Kahlief was pronounced dead an hour later — at the same hospital where his uncle Kamal Myrick died roughly five years earlier.

A warrant was issued for a man’s arrest in connection with Kahlief’s death, but he is not yet in custody, according to the most recent available information from law enforcement.

As of the week of Aug. 10, there have been 1,422 shootings in Philadelphia this year, a 3% increase from roughly the same time period in 2021. One hundred thirty-two children have been shot in the city in 2022, and 21 children, mostly Black or Latino, have been killed by gunfire.

Statistics from the Philadelphia Police Department also show that from 2019 to 2022, Black male teens in Philadelphia comprised the majority of deaths and suspects in shootings.

School district and city leaders’ proposed solutions to gun violence’s effects on young people cover different issues.

In November 2020, Councilmember Katherine Gilmore Richardson sponsored a hearing on providing conflict resolution to all district students. In April 2021, two months after Kahlief’s death, Richardson’s office reconvened the hearing, and the district committed to providing conflict resolution programming in every school beginning last year.

“By offering conflict resolution training to all students, we will be taking a preventive approach to violence reduction,” Richardson said.

Meanwhile, last June, City Councilman Kenyatta Johnson joined other officials at John Bartram High School to pitch funding for security cameras in neighborhoods around schools where students have been most affected by gun violence. Christopher Braxton, a senior at Bartram, was shot and killed in January near the campus shortly after the end of the school day.

Those cameras will be installed as part of the district’s school safety plan for the 2022-23 school year. Kevin Bethel, the district’s top school safety officer, said the plan also includes an increased police presence around schools during arrival and dismissal times, and a “safe paths” program for areas around eight high schools.

Johnson said he’s concerned about any homicide that happens in his district, but that “it hits home” when a young person like Kahlief loses his life.

“My resolve is even stronger to strategize and figure out ways on how we keep our young people safe. I believe that starts with listening to our young people and making sure they have a seat at the table,” Johnson told Chalkbeat.

During a rally outside City Hall earlier this year, students from nine high schools presented findings from a gun violence survey of 1,300 students. That survey, part of a report commissioned by the Philadelphia City Council, revealed that 95% of students said they couldn’t name a neighborhood organization where they could go to talk about the impact of gun violence.

Students who provided feedback for the report said that the epidemic of gun violence is also a racial justice crisis, because shootings disproportionately impact Black communities that have high rates of poverty and unemployment.

The report also indicated that just like law enforcement and the court system, students’ perception of school suffers when they report heightened fear of criminal activity and violence.

“Youth who are exposed to neighborhood crime, poverty, racism, and educational disadvantage report reduced trust in institutions,” the report stated, citing research. “This distrust extends to schools and is a factor in school disengagement.”

Healing a grieving school family

When students like Kahlief die, the district has a process and resources available to help students and educators at each school. But they tell just part of the story of how school communities respond and come together.

School officials mobilize extra mental health professionals to a specific school, like Southern, that’s acutely affected by gun violence, and makes free outpatient counseling sessions available to staff. Typically, the district will send counselors to a particular school to help students talk through what they are feeling.

The district also has an around-the-clock helpline for grieving children that is answered by a clinician.

Schools like Southern have situations that need intensive interventions, because there are layers of trauma that should be addressed, said Abby Gray, the district’s deputy chief of the Office of School Climate and Culture.

“We’re adding new staff, we’re adding new programming, we’re adding new external partnerships,” Gray said. “We’re trying to keep up with the need. There’s a lot of need there.”

Jayme Banks, deputy chief of prevention, intervention, and trauma services for the district, said that while there’s more the district can do to support schools suffering from gun violence, leaders do try to be flexible and make sure help doesn’t stop unnecessarily at certain barriers.

“We have even opened up school buildings on the weekend for some events as well when more community response was needed,” Banks said.

“Kahlief loved hard. His big thing was he needed to feel how he made others feel. And that was a big disappointment for him, when he didn’t get the love back that he always gave out.”

When students die, administrators at their respective schools get “white papers’’ that make the news official. But Latoyia Bailey, who was the assistant principal at Southern for the 9th and 10th grades while Kahlief attended the school, indicated that this bureaucratic process wasn’t truly necessary.

“Because we have people working at the school who know him very well, because they grew up with his family, we knew about his death before the white papers even came,” said Bailey, who is now the principal of the Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush High School in Northeast Philadelphia. “I remember trying to get myself together, not knowing what the day was going to be like.”

What happened next at the school took Joe Gaines, the school’s clinical coordinator for counseling services, by surprise.

The same day that students at Southern — who were learning virtually at the time — received word of Kahlief’s death, Gaines noticed a ripple effect of grief.

“It was the first time where I saw students sort of actively reach out to myself and to counselors and administrators and say: We need to talk about this as a student body, we need a space where we can talk about this,” he said.

This outpouring from the students prompted Southern’s leadership to strategize. Staff changed the day’s schedule and blocked off time for a virtual town hall. Typically, many students skip school-wide events. But the event to mark Kahlief’s death and allow students the space to express their feelings was different, Gaines recalled. The majority of students showed up in some form, and there was a lot of grief.

“It was really heart wrenching,” he said. “Not only have we just lost a student who had so much promise, but then you also really felt for these kids who just didn’t quite understand how this happened and seems to sort of keep happening and what’s going to happen next.”

And while usually, not many students take advantage of the counselors who visit schools who have lost a student in similar circumstances, that wasn’t the case at Kahlief’s death, Gaines said.

After the virtual town hall for students was over, staff at Southern also came together virtually later the same day to heal and discuss the situation.

One outcome of these events was the staff’s realization that students wanted an immediate recognition of Kahlief’s life. After learning about Kahlief’s death on a Friday, they held a memorial service the following Monday, and students submitted pictures of Kahlief for it. It allowed another chance for students to “pour out publicly how they felt,” Bailey said.

In addition, the actions and events overseen by staff and students at Southern laid the groundwork for how the school could respond to such tragedies in the future, even if it’s a response nobody wants to contemplate.

“I just wanted to make sure that even long after I left that was something that was put in place because of the hurt and the harm that Kahlief’s death had on the school community,” Bailey said.

But even those heartfelt and potentially long-lasting responses, of course, don’t protect everyone from intense feelings of loss and anger.

When a popular student like Kahlief dies, some of the fallout is relatively easy to see, like students who lose the ability to focus on their studies. But Fitzgerald, Kahlief’s one-time teacher, said that in the wake of such incidents, unexpected behavior and undiagnosed mental health conditions can be harder for adults to identify and get a handle on.

“If you lose a student in a school, of course, everybody knows it affects his friends,” Fitzgerald said. “But there are other kids that could just have an existential crisis. It could trigger their own feelings. So it can affect a lot of kids in a different way that you wouldn’t even be able to track back to.”

After Kahlief died, Deagejah Comer, his close friend who warned him to be safe, ended up going to a therapist. But she ultimately didn’t see the point of explaining to the therapist why she was feeling what she felt.

In the wake of Kahlief’s death, when she went to school, Comer — who was once on the honor roll — couldn’t pay attention in class. She spent half a school year crying in a counselor’s office. Comer did graduate from Constitution High School this spring, but she said she is still depressed.

When she thinks about what needs to happen to prevent tragedies like Kahlief’s death, her mind turns to Philadelphia and its leaders.

“I feel like the city needs to take control,” Comer said. “They need to call some reinforcements or something, because it’s getting crazy and it’s only going to get worse.”

Comer can’t say how many people she’s gone to school with have died. If she starts to count them on her hands, she runs out of fingers.

Bureau Chief Johann Calhoun covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. He oversees Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s education coverage. Contact Johann at jcalhoun@chalkbeat.org.