Every year, hundreds of students in some of Philadelphia’s poorest neighborhoods can’t apply to the city’s most prestigious high school for a simple reason: They can’t take eighth grade algebra at their local public school.

The advanced math course is only offered in 50 of 195 K-8 and middle schools in the district that have eighth grades. A review by Chalkbeat of the schools where algebra is offered, and the schools that recently began offering it, shows a pattern:

In general, the lower the median household income in the school’s surrounding neighborhood, the less likely that algebra is available to eighth graders.

Students who attend schools where algebra is not offered are automatically shut out of applying to Masterman in high school, the district’s most selective school, because the course is a prerequisite for admission. The requirement has been in place for at least 20 years, according to district spokesperson Marissa Orbanek.

The fact that algebra is a barrier to entry at one of Philadelphia’s premier schools highlights challenges with the district’s efforts to revamp admissions in the name of equity and to overhaul its math curriculum.

Philadelphia’s approach to the course underscores a national debate about the importance of eighth grade algebra. Some say that early algebra can set students on a path to completing calculus in high school, often a prerequisite for those seeking to be STEM majors in college. But others say such an approach can exacerbate inequality without giving most students an understanding of practical math they need to succeed in life.

In 2014, San Francisco prohibited eighth grade algebra because different student groups had vastly different outcomes. But now there’s a movement afoot in the city to change that. Cambridge, Massachusetts schools recently stopped offering eighth grade algebra. The debate has also raged in New York City where a mandate to expand and standardize the way algebra is taught has received polarizing feedback from teachers.

Janine Remillard, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education who is an expert on math curriculum, said research shows that the outcomes for students who take algebra in eighth instead of ninth grade are a “mixed bag.” That aside, she said, the eighth grade requirement means that admission “is really about what school you went to” before Masterman.

“It’s enormously problematic that Masterman is using eighth grade algebra as criterion in a district where equity issues are so much at play,” Remillard said.

Current decisions about where to offer algebra in eighth grade are based on analysis of sixth and seventh grade student math performance, Orbanek said, as well as input from principals and central office staff.

“Equity of access, even surrounding Algebra I, still needs to be worked on,” said Jeannine Payne, who has been principal of Masterman since 2021.

Payne, who formerly led two North Philadelphia elementary schools that rarely sent students to Masterman, said when taking the job that she wanted to create more opportunities at the magnet school.

Making eighth grade algebra more widely available is part of Superintendent Tony Watlington’s plans for a $70 million curriculum overhaul that began this school year with math. But the lack of access to algebra illustrates that a huge investment in new materials alone does not necessarily address serious concerns about inequity, and that current practices can deny students opportunities that extend beyond just admission to Masterman, said Remillard.

Orbanek said a team is reviewing how and where the district currently offers the course. The district did not make anyone on that team available for an interview.

There is a district program in which eighth graders at several schools jointly take the same algebra class. But that effort, which is called Cross School Learning and began last school year, still leaves many students without access to the course in eighth grade. The program started with three schools and now includes 16.

At the October Board of Education meeting, Watlington shared state test score data showing declines in algebra proficiency from 2018-19 to 2022-23 of 6.6 percentage points among district students, and an increase in below basic scores of 8.3 percentage points, even as PSSA scores for grades 3-8 improved between 2021-2 and 2022-3. On this year’s state math exams overall, just 20.4% of students scored proficient or better, an improvement on 2022 but slightly below pre-COVID achievement.

“If kids are not prepared, why offer [8th grade algebra]?,” Remillard said. “That’s a problematic approach as well.”

Which students can get into Masterman?

Getting into Masterman is already very challenging, especially for those seeking to begin in ninth grade rather than in fifth grade, the earliest students can enroll. Historically, no more than roughly 10% of students have been admitted to Masterman just for high school. But that percentage is changing.

For decades, Masterman’s enrollment has seldom reflected that of the district as a whole — it is predominantly white and Asian, while the district is made up of mostly Black and Latino students. That disparity sparked protests in 2020 after the killing of George Floyd.

Two years ago, in an effort to broaden access for two dozen criteria-based schools, the district overhauled its admissions system, including for Masterman. In place of a process that gave most of the power to individual principals to choose from among qualified students, it established a citywide lottery.

The lottery gave automatic admission to students from historically underrepresented ZIP codes, most in North and West Philadelphia, to their top choice school — if they qualified based on their grades, test scores, and other potential factors.

But just five of the 28 schools that have an eighth grade in the targeted ZIP codes — which are mostly in North Philadelphia — offer algebra in eighth grade, according to information from the district.

Two of the schools in the priority ZIP codes that do offer the course in eighth grade, Carver High School of Engineering and Science, which includes grades 7-12, and Conwell Middle Magnet, are not neighborhood schools and have their own admissions requirements. In Carver’s case, most of the eighth graders stay there for high school.

“Until you put algebra in all those schools, having it as a requirement for entry to any high school is inequitable,” said one district official, who was not authorized to speak publicly and spoke on the condition of anonymity. “Even if your plan is to put algebra everywhere in eighth grade, we don’t have it yet. How is it just, how can you say you’re creating more equity and favoring some ZIP codes, if students are coming from schools located there that t don’t offer it?”

Since the district switched to a lottery to determine final admission to the district’s most selective schools, the percentage of students entering Masterman in ninth grade has increased to about 30% in the current school year because, unlike in the past several years, eligible Masterman eighth graders were no longer automatically offered a spot in ninth grade.

But the district announced it will go back to automatic admission for eighth graders into the ninth grade starting in 2024-25, which could reduce the percentage again.

Expansion of eighth grade algebra uses hybrid classes

Citywide, student success in algebra classes has also varied significantly between the eighth and ninth grade in a way that suggests preparedness for algebra doesn’t necessarily improve as students get older. Last year, nearly 15% of the 8,300 students who took algebra in ninth grade didn’t pass the course, while only seven of the nearly 1,400 students who took it in eighth grade didn’t pass, according to data the district provided to Chalkbeat.

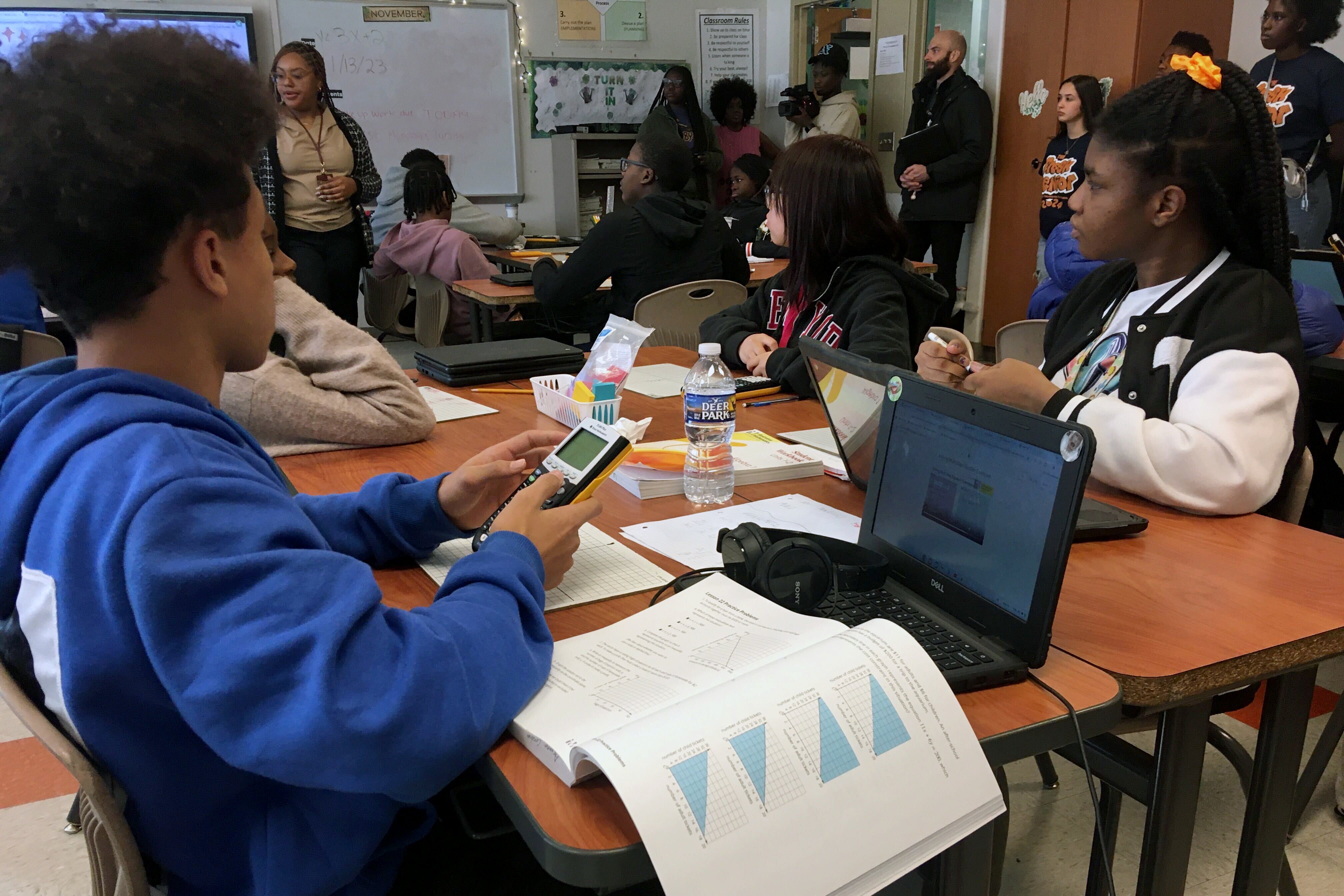

The district is trying at least one approach to increase access. In its Cross School Learning program, selected eighth grade students from several schools take algebra classes jointly.

The hybrid online and in-person program started in the 2022-23 school year at J.S. Jenks, Lingelbach, and Shawmont elementary schools. This year, it expanded to 13 more schools, which are among the 50 that the district lists as making eighth grade algebra available.

There are currently five teachers who give lessons in three schools each. The teachers travel from school to school, providing in-person instruction in one while the other two schools are virtual.

The decision where to expand the Cross Schools Learning program was based on an analysis of sixth and seventh grade student math performance, said Orbanek, the spokesperson, as well as input from principals and teachers. Students in algebra also receive regular eighth grade math instruction so they can be prepared for state math tests.

“Cross Schools Learning has been vital for our school this year,” Jenks Principal Corinne Scioli said in a video promoting Cross School Learning. “So many of our eighth grade students are not having the opportunity to apply and be considered for some of our most competitive high schools in the city.”

Correction: Nov. 17, 2023: Decisions about whether to offer algebra in eighth grade are made with input from principals and central office staff. Due to incorrect information provided by the school district, a previous version of this article said union leaders were involved in the decisionmaking.

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.