This story is featured in Chalkbeat’s 2023 Philadelphia Early Childhood Education Guide on efforts to improve outcomes for the city’s youngest learners. To keep up with early childhood education and Philadelphia’s public schools, sign up for our free newsletter here.

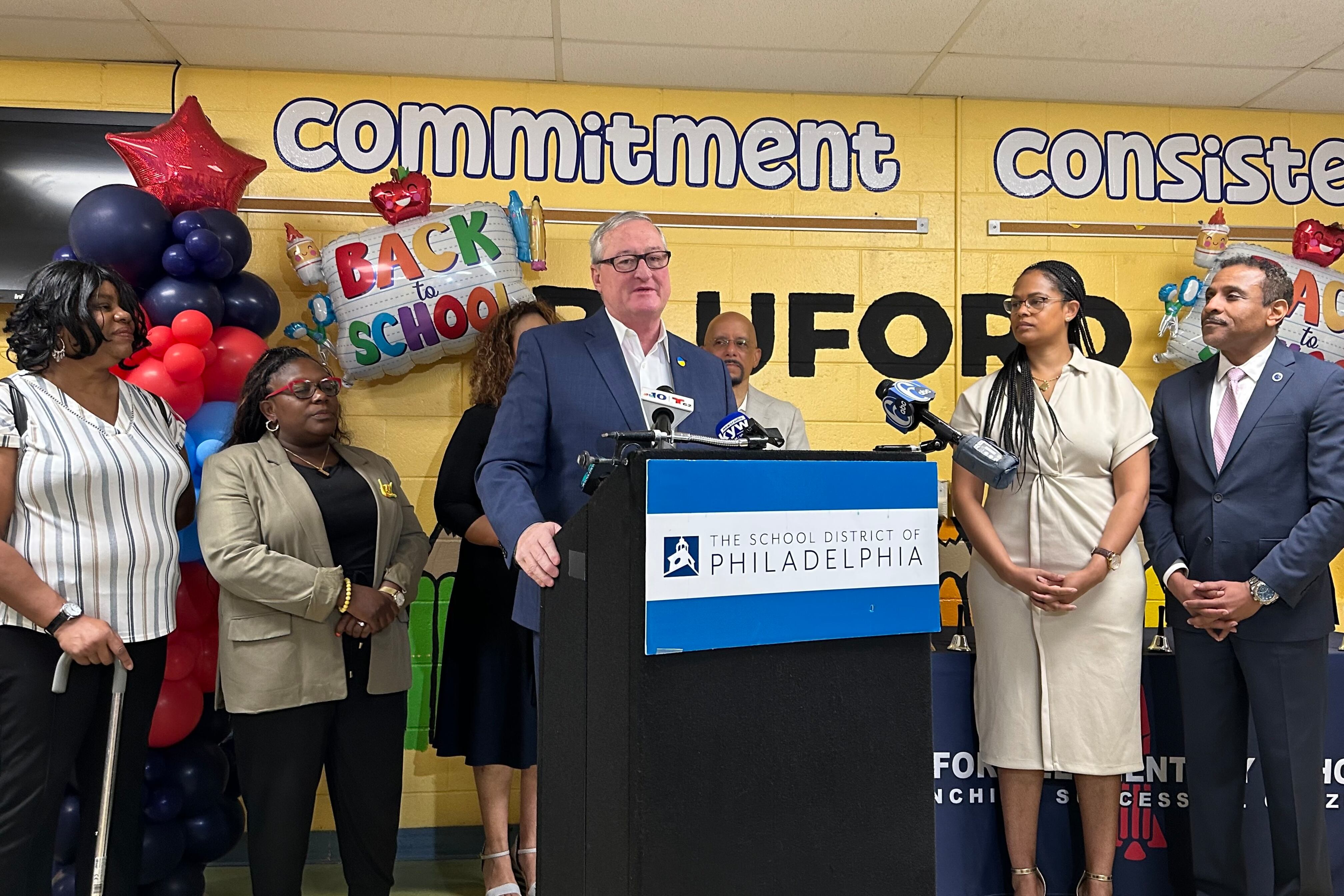

When Mayor Jim Kenney is feeling frustrated, he said, he has a guaranteed pick-me-up: He goes to visit students in a local prekindergarten.

“When I get really down, and depressed, and disgusted, and lots of other adjectives, I go schedule a pre-K visit,” Kenney told Chalkbeat in a candid interview conducted during his final weeks in office. “It’s like my salvation.”

Along with overseeing the school district’s return to local control after 17 years under state authority, Kenney regards the establishment of PHLpreK, which allows thousands of 3- and 4-year-olds in the city to attend prekindergarten free of charge, as one of the major legacies of his two terms in office.

“I believe the only way out of poverty and into a successful life is education,” he said, by way of explaining his commitment to the issue. Providing structured programs for 3- and 4-year-olds, he said, “sets the tone for the rest of their educational experience.”

As policymakers consider how to overhaul the state’s school funding system to make it fairer for districts like Philadelphia’s, Kenney also pointed out that the city increased its contribution to the school district by $1.5 billion during his tenure.

This year, more than 5,000 children are enrolled in PHLpreK, according to a report from Kenney’s office. Since its inception in 2017, more than 17,000 children have passed through the program and over 500 new teachers have been hired to work in PHLpreK classrooms, the report said.

Making free, high-quality prekindergarten more accessible helped parents and caregivers of young children hold down jobs, Kenney said, which in turn reduced poverty and led to more stable families – in itself an important factor in promoting school readiness.

While there isn’t research on PHLpreK’s impact that tracks students who had access to early childhood education versus those who didn’t, Kenney said third grade reading scores went up 3 percentage points last year in district schools. Those third graders were the first class of children who had access to PHLpreK.

To be sure, that increase is modest. The district set a goal for 62% of third graders to score proficient on the state exam by 2026. But in the 2022-23 school year, only 31.2% of third graders scored proficient or above on their state exams.

Beyond the numbers, Kenney cites anecdotal evidence that PHLpreK is having an impact. He loves to tell the story of visiting a kindergarten on the first day of school. “It was a disaster,” he said, with children bawling and clinging to their mothers — except for two kids sitting placidly in their seats, hands folded in front of them.

“I said to them, ‘Did you go to pre-K?’ They did. They knew exactly what to do,” Kenney recalled. “There was no learning curve.”

To get free pre-K done, Kenney fought off the soda industry, which spent millions trying to kill the sweetened beverage tax he proposed to fund the program. (The City Council approved the 1.5 cents-per-ounce tax on those beverages in a 13-4 vote in 2016.)

“They hired every lobbyist in the universe,” he said. “But we had all the parents. And ladies with babies strapped to their chests can be a powerful force.”

Kenney said he voted against the tax twice during his time on the council in 2010 and 2011 when then-Mayor Michael Nutter brought it to the table. Nutter had emphasized the health benefits of reducing soda consumption, which didn’t resonate with the council members at the time.

What changed Kenney’s mind? If he wanted free pre-K, he would need to establish a sustainable funding source.

“Once we got sworn in. We’re sitting in my office … and I said, well, how are we going to pay for all this stuff?” Kenney said.

Having a dedicated purpose for the tax revenue was enough to convince the council members to back the tax.

But in its first few years, hampered by an ongoing lawsuit against the soda tax and diminished state revenues during the pandemic, the program was slow to roll out and expand. A city controller’s audit in 2017 found some “missteps” with the program’s implementation, including over-billing and under-enrolling.

But Kenney said he never considered giving up on the effort.

“Head down, win or lose,” Kenney said. “I don’t know what we would have done if we had lost in court. But we didn’t.”

The state Supreme Court upheld the beverage tax in a 4-2 vote in 2018. Kenney said he hopes the program will continue to expand after he leaves.

It’s unclear what the future will hold for the program when Kenney vacates his position. A spokesperson for mayor-elect Cherelle Parker declined to comment on the program..

Kenney said he hasn’t had the expansion discussion with Parker’s team yet. But he thinks it’s “politically powerful enough” that “if somebody tries to take it away, I don’t think that they would get a good reception.”

In his waning days as mayor, Kenney has been thinking about what he’ll do next. He said he intends to set off on an ocean cruise the day after Parker is inaugurated. After that, he’s not sure. But it won’t be public life.

“I’m done with it. It’s time for people to move on sometimes,” Kenney said.

He said one idea he’s mulling is starting a nonprofit that would raise money to expose city kids to more live arts and culture programs, he said.

As a high school freshman at St. Joseph’s Preparatory School, Kenney said he and his classmates were taken on a field trip to see the Alvin Ailey Dance Company and its legendary founder, Judith Jamison, perform at the Walnut Street Theater.

“I went from hating it to thinking, ‘This is beautiful. I’ve never seen anyone move like that. I’ve never seen anything like this,’” Kenney said. “I honestly believe that kids in the city, who see nothing but chaos and hurt, [deserve] an opportunity to do that, to see that there’s beautiful things in the world.”

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.

Carly Sitrin is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Philadelphia. Contact Carly at csitrin@chalkbeat.org.