In August, when Philadelphia district officials briefed their high school teachers and administrators on the state’s new graduation requirements, Sayre High School Assistant Principal Nina Brevard could only react with worry and disbelief.

“We were all scared,” she said. “We thought, ‘You want us to do what, by when?’”

Until this school year, in order to graduate from Philadelphia public schools, students needed to complete a senior project and earn 23.5 credits distributed across four subjects: English Language Arts, math, science, and social studies. But starting with the Class of 2023, they also have to meet at least one of five graduation pathways under a law enacted in 2018 called Act 158.

In theory, the most straightforward one is to score proficient or advanced on three Keystone exams in English literature, biology, and algebra. Alternatively, they can score proficient or advanced on one Keystone and not score below basic on either of the other two while having a composite score that reaches a minimum threshold.

Not many students would make it either way at Sayre, a small high school in West Philadelphia with an enrollment of fewer than 400 students, including 90 seniors, most of whom come from challenging socioeconomic circumstances.

In 2018-19, the last full school year before COVID disrupted state exams, just 11% of Sayre students scored proficient or advanced on the English Keystone, just 2% did so in biology, and not one student scored that high in math. The school’s four-year graduation rate was just 61% in 2021-22, compared to 75% district-wide the same year, while just 26% of Sayre’s students go on to college, according to recent data.

So at first, the law seemed to impose a new mandate on students and teachers already struggling with difficult circumstances. But what started out as a daunting, government-mandated task — what some feared would create another barrier for struggling students and more work for already overwhelmed educators — has led to a largely positive response from students and staff who are working hard and in new ways to achieve it.

For one thing, it has focused students on considering their futures. Principal Jamie Eberle said that before this year, many students had no idea about their post-graduation plans.

The pathways, which include opportunities for internships and industry certifications, encourage them to think long-term beyond just taking required courses that may not interest them.

The school also has had a proactive strategy. Teachers became directly responsible for monitoring students’ progress and helping them stay on track. School administrators began the year by laying out clear information to parents as well as students. And Sayre staff, in turn, encouraged students to come to them with concerns and hold them accountable.

“The easiest way to attack it is to make sure all students are touched by a caring adult,” said Eberle.

Although there’s still lingering skepticism and uncertainty about the new graduation rule, students have largely embraced the pathways requirement as worthwhile.

When junior Sheanee Bentley, 16, first heard about the new mandate, “I thought they were doing too much. But the more it was explained, I thought it was good.”

She said it “helped students think about how to navigate after you get out of high school.”

She intends to take the armed forces qualifying test to satisfy Act 158.

Looking beyond standardized tests for a diploma

In 2018, amid concerns about the value of a high school diploma, the Pennsylvania General Assembly discussed legislation that would require students to pass the three Keystone exams in order to graduate.

But teachers unions and others raised concerns about overreliance on standardized tests as such a crucial gatekeeper, especially given wide disparities in district resources and data showing that students of color and those from low-income backgrounds were less likely to do well on them.

The bill that became Act 158, enacted that year, grew out of this concern. It outlined the additional pathways, which were originally slated to become effective for the Class of 2021; the state pushed back that date by two years due to COVID.

The three pathways that don’t hinge on Keystone exams rely on various factors, including other tests.

First, students can use the pathway of achieving minimum scores on the PSAT, SAT, or ACT, which are college entrance tests, or the ASVAB Armed Forces Qualifying Test. As part of this pathway, they can also score well on AP and International Baccalaureate exams in the Keystone subjects in which they were not proficient, successfully complete courses in those subjects, complete an apprenticeship program, or be accepted into a four-year college.

Second, career and technical education students can satisfy one of the pathways by getting an industry certification. They can do this by passing the industry-standard test, called the NOCTI, in their specialty. Students not already on the career-technical education track in school can satisfy this pathway by earning an industry certification on their own. Examples of such certifications are those needed to work with children, such as being a mandated reporter and learning CPR.

Third, students can attain three goals from a list of 12 items. These include minimum scores on the SAT, Advanced Placement, and International Baccalaureate exams; successful completion of a college-level course; a letter guaranteeing employment; military enlistment; or acceptance to a postsecondary institution that is not a four-year college.

The challenge Sayre faces with respect to the Keystone pathways isn’t unusual. School district officials told the City Council at a hearing last month that, in the district as a whole, just 26% of students score proficient or advanced on all three Keystones.

District spokesperson Christina Clark said Tuesday that of the district’s 8,120 seniors, roughly 3,815 (about 47%) had achieved an Act 158 pathway and were also on track for the credit requirements. Roughly 4,220 seniors, or 52%, had achieved a pathway, according to the district.

“This is doable. We have to make sure students have what they need,” Deputy Superintendent Shavon Savage told the council.

At Sayre, a few seniors did get sufficient Keystone scores to put them on track to graduate, Brevard said, and a few are retaking the tests. But many never took the test at all, either because of the pandemic or because they hadn’t previously been enrolled in school in Pennsylvania before coming to Sayre.

Sayre has a highly transient population, with students from disparate backgrounds coming and going throughout the year.

Recently, the school got new students from as nearby as Lancaster, Pa., and as far away as Bangladesh, Canada, and Jamaica, Eberle said.

In addition, about 85% of the students come from low-income families, and four out of 10 students receive some form of special education services.

Students and staff proud of achievements

At the beginning of the school year during orientation, Eberle and Brevard held a town hall-style meeting with the seniors and their parents to make sure they understood what the graduation requirements were and what it would mean for them.

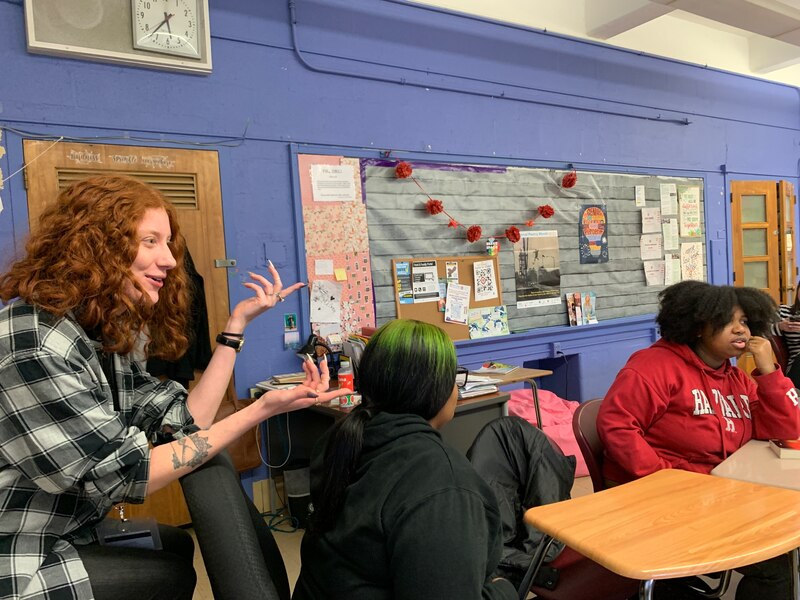

As the school leaders explained what was happening, many parents and students “were looking lost,” Brevard said. But that gradually changed. Once the school year was underway, seven teachers and Brevard each each took on a caseload of seniors, approximately 10 each, to guide through the process.

Just as important, Eberle and Brevard wanted students to take ownership of the process. So they told students that they should expect the person monitoring their Act 158 progress to contact them and stay in touch.

“You have the power now, come tell me if they haven’t seen you,” Eberle said. “We were giving students the power to hold adults accountable.”

Despite her early skepticism, Brevard has reached the conclusion that the requirement benefits students. After all, not every student’s strength is passing tests like the Keystones.

“I tell them that these are things you can put on your resumes,” Brevard said. “When they apply for jobs, especially those who are not college bound, they already have some certifications like CPR.”

And then there are less quantifiable benefits, like the pride Brevard said that students feel when they meet the requirements of a pathway, and how they go from feeling “frazzled” to having a new skill set.

Nia Devard, 17, a junior at Sayre, said she finds it “kind of amazing” that she satisfied two of the pathways by achieving an acceptable score on the PSAT and on the test necessary to enter the military, the ASVAB.

Many other students have similar sentiments, although not all their concerns about post-graduation plans have gone away.

Noah Williams, 18, a senior on the basketball team, satisfied one pathway by scoring well enough on the test to qualify for the military. He plans to enter the Marines “because that’s the hardest” of the military service branches, he said.

He is proud of his achievement. Still, he worries about his peers. While acceptance to college helps satisfy one pathway, higher education isn’t a practical option for some.

“What if they can’t afford college?” he said.

Then there are the students who had to adjust to more than a new state law. Cinthia Rosario, 17, came from West New York, N.J., to Sayre for the 12th grade last summer.

Meeting the pathway was just one more big thing she had to worry about at Sayre. “It was hard,” said Rosario, who is originally from the Dominican Republic. “I had to get used to a new school, new people, new state.”

But she is fitting in. She is a cheerleader, and she has already met a pathway: she has been accepted into Indiana University of Pennsylvania, and she wants to study psychology.

Social studies teacher Joseph Fafara is one of the teachers with a caseload of students. At first, he thought the whole process would be unwieldy.

But with “teamwork and effort,” he said, the task has been manageable for staff and students. He’s been pleasantly surprised so far.

“Preparing students for the next step in life is what our job is,” Farfara said.

Kate Conroy, another of the teacher-mentors, is hopeful about the requirements but harbors some doubts. She is concerned that due to the pathways the school district dropped the requirement for a research-intensive senior project, although the pathways offer the option for one.

“Will more students go to college, and will more students stay in college?” she said. “I guess you could say I am slightly skeptical that this will achieve what the state hopes it will achieve, but I would love to be proven wrong.”

In addition to making sure this year’s seniors are on track to meet a pathway, Sayre is also working on preparing younger students for what’s ahead.

Echoing Brevard’s comments, sophomore Sage Turner, 16, said the requirement “helps people focus.”

“I feel like, okay, they are difficult,” she said of the pathway requirements. “But that’s in order to see what people are really made of.”

She is a career and technical education student who is planning to go into nursing, and hopes that she can meet the pathways by getting a health-related certification.

“That is my passion,” she said.

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.