Asbestos scare or not, the show must go on.

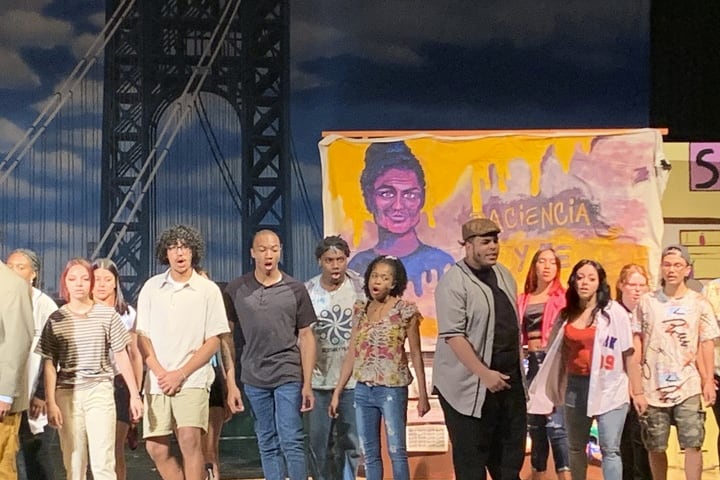

When Philadelphia’s Frankford High School closed in early April due to the discovery of loose, dangerous asbestos in the building, a cast and crew of more than two dozen students were working hard on a production of “In the Heights,” the musical about the hopes, dreams, and travails of young people living in the barrio in Washington Heights near the George Washington Bridge in New York City.

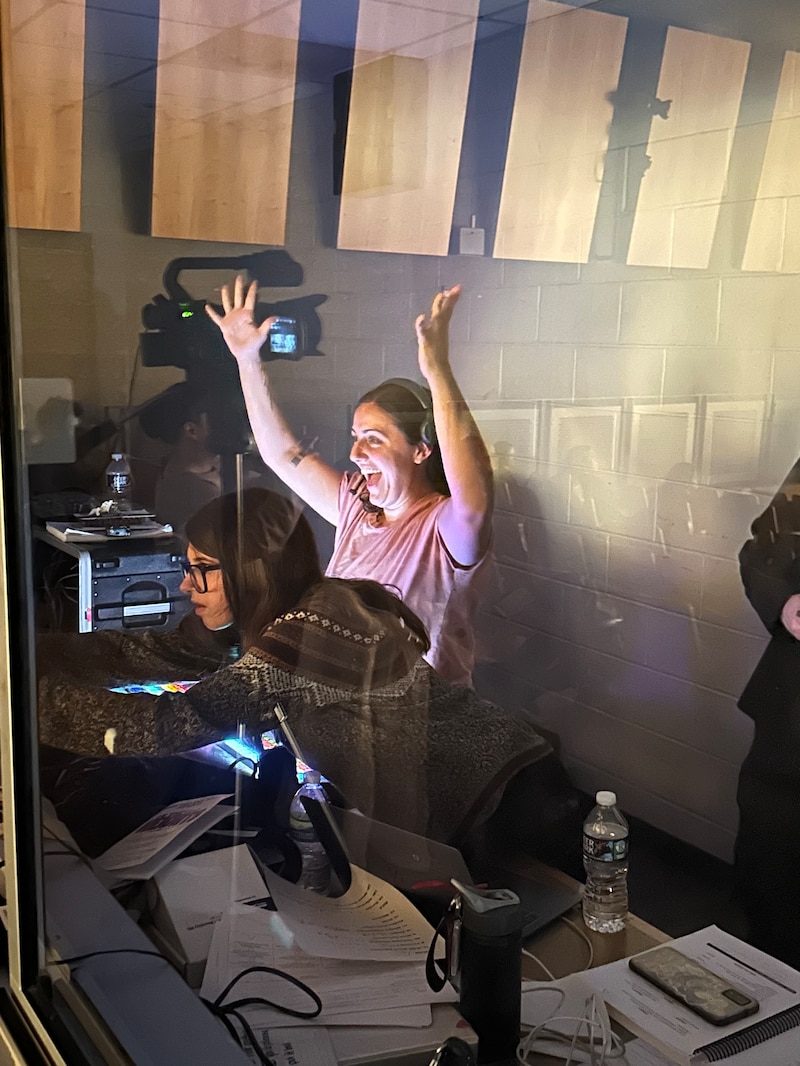

The show’s music director Rebecca Wizov couldn’t believe it. Of all the challenges that come with working in the Philadelphia school district, this was a new one. The students had been rehearsing since December.

But Wizov, a Frankford teacher, and Frankford Principal Michael Calderone sprang into action. “We went into full damage control, finding a venue to switch the performance to,” Wizov said.

Last week, their efforts paid off as the students put on an exuberant production of the show — which put “Hamilton” creator Lin-Manuel Miranda on the map and was co-written by Philadelphia native Quiara Alegría Hudes — at Kensington Creative and Performing Arts High School before ecstatic audiences of family and friends. They staged three performances on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday.

The journey was a “crazy roller coaster,” said Jaden Colon-Torres, a sophomore who starred as Usnavi, the open-hearted bodega owner who longs for his native Dominican Republic. “But we made it happen.”

After Frankford closed, the students first moved rehearsals to nearby Harding Middle School. Then, when the weather turned nice, they switched to the grand elevated space outside the main entrance of Frankford, a mammoth, nearly century-old building on Oxford Avenue.

The original plan was to put on the show at Fels High School, a little over a mile away from Frankford (which is slated to stay closed the rest of this school year as the district seeks an alternative space to resume in-person learning). Shortly after the school building closed on April 7, the district sent over vans to move the set pieces, costumes and props, but none of the school employees were allowed inside the building to retrieve them. Workers in protective gear were sent over to help.

“We had to make a detailed list.” Wizov said. “That was hard, but we were able to do it.”

The vans were on their way to Fels, Calderone said, when he got word that the sound system there wasn’t working properly. Calderone then called Patricia McDermott, Kensington CAPA’s principal who had previously worked with him at Frankford, begging her to let Frankford’s students perform the show at her school instead. McDermott agreed.

The vans “had left the parking lot,” he said. “We rerouted them.”

Kensington CAPA is more than four miles away from Frankford on Front Street, but thankfully, Wizov said, “super accessible by SEPTA.”

As soon as Kensington CAPA was secured, “We assembled to be able to do a Saturday rehearsal” at the new space mere weeks before the show was scheduled to open, Wizov said. The district let the school keep the vans to help transport students. Wizov and the other directors drove the vans themselves.

Calderone, meanwhile, was totally on board but also disappointed. He had been working for seven years to get a new sound system installed at Frankford, and it was finally finished six weeks ago. He was looking forward to testing it out on this show.

It wasn’t to be.

“That one hurt,” he said.

Reviving a Philadelphia school’s arts programs

Since Calderone arrived at Frankford in 2015, he had worked hard to rebuild the school’s arts program, a casualty of severe cutbacks forced on the school district a decade ago when former Gov. Tom Corbett and state GOP lawmakers slashed education spending.

“When I came we only had one visual arts teacher,” he said. “Our music teacher resigned right before the school year started.”

Not “an arts kid” himself — he played football at Archbishop John Carroll High School— Calderone gradually brought back instrumental and vocal music teachers, as well as instructors in visual arts, digital media, and ceramics, as education spending and the district’s budget saw somewhat better days during the administration of Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf.

“I know how important it is for kids,” Calderon said. “I wanted them to have it. Ms. Wizov and [instrumental teacher Brittany Cramer] built this program from the ground up. I hired both as brand new teachers. It’s definitely something I tried to prioritize.”

Dawn Madden has taught social studies at Frankford for two decades, and at Friday night’s show, the second of the three performances, she was helping take tickets at the door.

For the first seven or eight years of her time at Frankford, the school put on a play or musical every year, she said. After the school’s music teachers left, an English teacher organized a production a few times, she said. “Then, for 10 years, it stopped,” she recalled.

Under Wizov and Cramer, the school eased back into theater, starting in 2017-18 with a musical showcase. Then the next year, Frankford put on “Footloose.” “You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown” was scheduled for spring 2020, but then COVID hit. Last year, the school put on “High School Musical.”

Bringing back the annual play or musical has been transformative, Madden said.

“I saw some of those kids that weren’t participating in anything, I saw them light up,” she said. “That spark was just back. It’s an entirely different vibe than it was for those 10-ish years when … we were just sports and academics. Those kids who weren’t in sports felt kind of left out.”

She noted that special education students have also gotten involved; at Frankford, 31% of students have Individualized Education Programs, or IEPs. One student in an autistic support class is a member of the ensemble and enthusiastically demonstrated his break dancing skills.

“It’s just wonderful because all the students can access it in some way,” Madden said.

Frank Machos, executive director of the district’s arts programming, said about half the district’s 50 high schools regularly put on plays or musicals. “It ebbs and flows,” he said, with the availability of teachers and other staff, and their interests and talents.

Frankford does not have a drama teacher, but math teacher Michael Sherman directed. “He’s a bit of a thespian himself,” Calderone explained.

Frankford, with more than 900 students, is about half Latino and nearly half Black, with a smattering of white students. With “In the Heights,” students get to play characters much like themselves and people in their families, like the kindly Abuela who raised Usnavi. For example, Nina Rosario, the lead female role, has “made it out” of the neighborhood, but comes home from Stanford in despair that she will lose her scholarship (although it all ends happily).

Dreamerly Jean Louis, a junior who played Nina, immigrated from Haiti in 2020 and speaks three languages, although not Spanish.

“When [the asbestos scare] all started, I thought the show was going to get canceled,” Louis said. She said she is “just grateful” they were able to pull it off. While she has sung in public before, “this was my first time doing a long show.”

Sophomore Zion Owens played Benny, one of the main characters. As a freshman last year, he starred as Troy in “High School Musical.” For this show, “We did so much rehearsal, so much effort, we had to make sure it was perfect,” he said.

Colon-Torres had no theatrical experience whatsoever before taking on his demanding role. When he auditioned, he feared he would not be cast at all.

“This is my first time ever, first time on stage, singing, talking, everything like that,” he said. “It’s been nerve-wracking, but it’s been one of the most exciting things in my life.”

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.