Mikayla Woody and Aniyah Brown-Johnson are spending part of their summer doing things that might make their friends jealous: crafting a social media strategy and setting up a TikTok account.

A few hallways over, other kids are studying African dance, growing basil and lavender, and constructing London’s Big Ben clock out of clay.

These students are not at summer camp, or stuck in a cubicle completing a marketing internship. It’s all part of their year-round school program at Philadelphia’s Belmont Charter School.

Belmont’s model might soon attract more attention. Democratic mayoral nominee Cherelle Parker — the city’s Democratic nominee for mayor and therefore the favorite to assume the office next year — has made year-round schooling part of her education platform. And Superintendent Tony Watlington included a pilot for year-round school in his five-year-plan adopted by the district in June. They’ve said it would be a worthwhile idea to explore in response to concerns about the pandemic and student safety.

But they have yet to release further details about their vision. And there are a host of questions and potential challenges linked to whether district schools have the funding, staffing, and desire from teachers and parents to adapt something like Belmont’s approach to more than 113,000 students in traditional district classrooms.

So parents and students have been left to wonder: Would year-round schooling mean academics for 12 months? Shorter and more frequent breaks around holidays? Or something akin to an educational camp during the traditional summer recess?

Officials at Belmont Charter Network schools in West Philadelphia say their long-running summer extension program could be an option for policymakers to consider. But making it work has required Belmont to be flexible and listen to parents.

Keeping school buildings open to ‘expand community’

Belmont charter schools educate over 1,200 students in pre-K-12 across three campuses, and their summer programming adds about seven weeks to the traditional 180-day school year.

Their buildings are open from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday during July and August, as well as the latter part of June; the school district’s last day for students was June 13.

This year, Belmont’s school buildings were closed for as few as four business days between the last day of the 2022-23 school year and the start of summer programming. But some campuses closed for six days. When it comes to putting breaks on the calendar for a year-round schedule, Belmont prioritizes flexibility.

Teachers working in summer learning programs were given a few weeks off between the end of the regular academic year and the start of summer programming. During those breaks for teachers, the charter network ran more camp activities and field trips. Those teachers will also get two weeks off before they go back to Belmont in the fall.

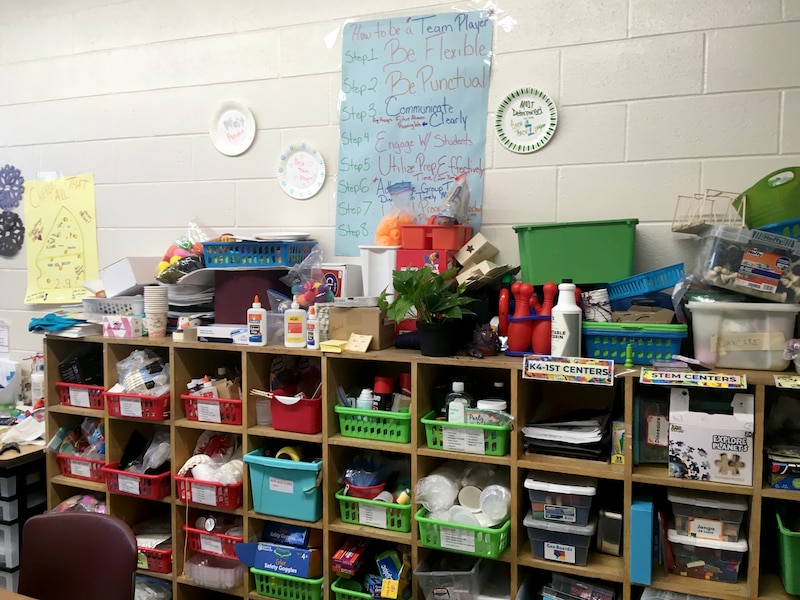

Belmont’s July and August programs offer 255 students the chance to participate in a combination of camp activities like swimming, sports, and crafts. There are also lessons on everything from Greek mythology and undersea biology to Egyptian mummies and European currency exchanges.

Though small, the summer programs are highly individualized, in terms of activities as well as scheduling. Younger children participate in camp-related activities during the day, while older students have more opportunities for work-study programs, job training, and classroom learning in small groups.

The network also offers paid internships for high school students, flexible schedules for those with jobs, field trips, and college tours. And it has community service requirements.

The Philadelphia school district also offers free academic programs during the summer, including special education programs, workforce training, and a “full day school-meets-camp experience,” at locations across the city. But not every district school building is open for these programs.

Beth Dyson, chief of staff for the charter network, said she thinks Belmont’s programming has been responsive to parents, students, and teachers. Belmont’s summer extension program has been running for nearly two decades, Dyson said, though it’s mostly “flown under the radar.”

Morgan Schrankel, a reading specialist at Belmont, put together the summer lessons on foreign currency exchanges and is leading arts activities for students.

She said working during the summer has allowed her to “expand her community” at Belmont by working with new students. It’s also given her an outlet to experiment with lesson plans.

“When I’m following a curriculum, when I’m worried about testing, when I’m doing all those things, I kind of have to do things one way. But this allows me to do things I’m passionate about,” she said.

The opportunities outside regular coursework at Belmont during the warmer months are also crucial. Woody said her summer internship has helped build her resume and prepared for life outside of and after high school.

“You’re actually gonna take these skills and apply [them] to something,” Woody said. “Build references, build your resume, and different things too because that can be hard. We don’t get a lot of chances. So it’s just like, work with what you’ve got, and know what’s being provided to you.”

Dyson said Belmont surveys parents and students continuously to learn about what’s working and what’s not.

For example, families reported wanting more child-care coverage for older students earlier in the summer and for young children later in the summer.

As a result, Belmont staggered starting dates for their middle school and high school programs and extended their early education summer programs further into August to accommodate family needs.

Year-round school is far from a panacea

When they’ve discussed year-round schooling, Parker and Watlington have said it’s one way to address learning disparities, provide child care for working parents, and give kids places to go during the summer.

For example, they’ve touted it as a way to help students who are struggling academically after COVID’s disruptions. Lagging state test scores have underscored worries about their progress and the district’s ability to meet its long-term goals.

Just 19% of all Belmont students scored proficient or advanced on state English language arts exams for the 2021-22 school year, an 11 point decrease from the previous year, and 4% did so in math. Belmont’s scores are lower than the traditional district schools’ results during the same time period.

There are other acute concerns beyond academics that Belmont tries to address. In recent years, people under the age of 18 have made up a growing number of gunshot victims —as well as perpetrators — in the city. Simultaneously, school climate ratings in the district have dipped. There are also city curfews and age restrictions limiting where young people can gather, and these can feel especially constraining in the summer.

That desire for students to feel “cared for and appreciated,” Dyson said, and that they feel like they’re making good use of their time, are big factors in how Belmont’s leaders have designed the year-round schooling program.

“The number one goal is for our kids to have a safe, consistent place to be,” said Jane Lawson, Belmont’s managing director of out of school time.

The first Belmont charter school started in 2002 following the state’s takeover of the district as the city’s first “turnaround school” in what was originally a district-run school. The network has grown to include five schools across three locations in Philadelphia.

Belmont has its critics. There’s been resistance to its attempts to grow over the years. And just before the pandemic, it attracted controversy regarding the sale of its district-owned building.

Dyson said Belmont has not been contacted by the Parker campaign or anyone from the school district to discuss their summer programming and how it fits into the network’s approach to year-round school. A spokesperson for the Parker campaign did not respond to requests for comment.

Getting funding, avoiding teacher burnout are key

Then there are hurdles related to dollars, cents, and staffing.

The pilot in the district’s five-year plan doesn’t include a cost or other details about potential year-round programming. Watlington has admitted the district lacks the funding to accomplish all of the goals in his strategic plan as the district faces long-term fiscal worries.

The Philadelphia Federation of Teachers union hasn’t commented on any year-round school proposal yet. But in order to make such a big shift, the district and the union would have to renegotiate the district’s teacher contract, which expires in August 2024. Such talks could be daunting.

A related issue: teacher burnout and turnover, which has become a national crisis. Philadelphia has faced significant staff turnover recently, and Pennsylvania as a whole faces a teacher shortage.

That was the backdrop for a simple question Woody had for Philadelphia education leaders: “Are y’all gonna be paying teachers more?”

She added that, in her experience, teachers are already “worn out” from expectations during the regular school year, and many may not be eager to keep working during the summer.

At the same time, to Dyson’s surprise, she said Belmont hasn’t really experienced challenges finding some regular classroom teachers willing to sign on for summer programming.

That also provides continuity for students, Dyson said, even if they work with teachers who aren’t their regular classroom teachers, because seeing someone familiar in the hallways helps students with feelings of anxiety about the next school year.

Tara Quinn, a former district teacher who is in her fifth year teaching at Belmont, said having sufficient break time for teacher “rejuvenation” is non-negotiable, something Woody and Brown-Johnson said is also necessary for students.

Without that time off, Quinn said, she would have seriously considered not teaching during the summer: “I need some kind of break.”

Then there’s the financial incentive. Quinn said having the opportunity to earn extra money during the summer was also a big motivator — she has a son in college and the extra income has been helpful.

Woody and Brown-Johnson said if they could advise Watlington and Parker, they would encourage the city to set up a year-round program that puts a focus on outdoor projects, field trips, and team-building activities for students.

Woody said the priority should be “something inspirational, educational, and fun. You don’t want to have busy work and boring work.”

Internships, work-study programs, or other job-related activities are also a must, they said.

But Brown-Johnson’s advice about the nuts and bolts of a good year-round program comes with a general caveat: She encouraged policymakers to think about making year-round school optional, not a mandatory one-size-fits-all solution.

Many students might not adjust well to being in classrooms year-round, she said. Rather, “everybody should have a say” in what their school’s program should look like.

Carly Sitrin is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Philadelphia. Contact Carly at csitrin@chalkbeat.org.