Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

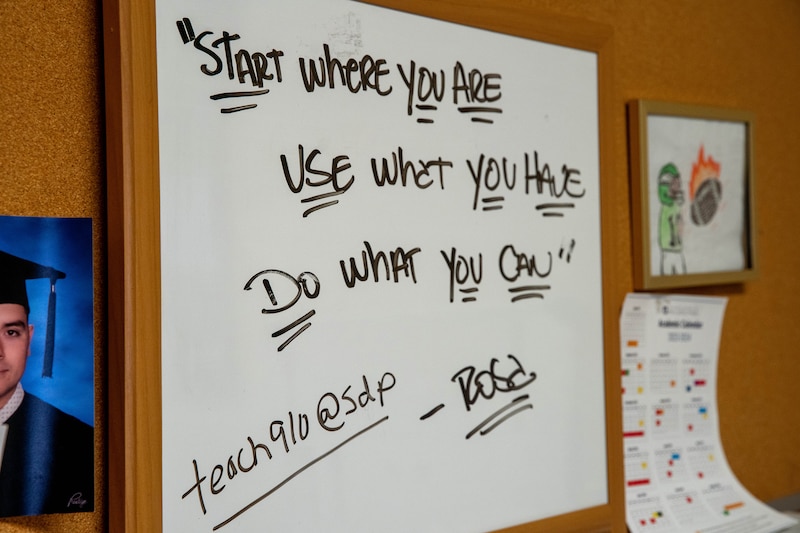

Kevin Rosa’s office at Bartram High School has a couch for conversations, a computer for recording music, and a stash of barbering supplies for anyone who needs a quick trim.

It’s also a place where students in the school’s Youth Violence Reduction Initiative can go when they’re involved in a conflict or just need a break.

Travis, 17, is one of 30 male students participating in the program. Travis said Rosa’s office would be his first stop if he felt himself falling in with people who might get him involved in a dangerous situation. “In this school that’s the only person I will really open up to,” he said. (Chalkbeat is using pseudonyms for students interviewed for this story to protect them from potential violence or threats of violence stemming from their participation in the program.)

As the program coordinator, Rosa juggles myriad responsibilities. He helps Travis and other students finish their schoolwork before they play video games or record rap tracks. If they have an unexcused absence from school, he visits their homes. Some of the students have been through the juvenile justice system, and some have violent incidents in their records.

“There’s a lot of things that we know that idle time does, so we try to fill the idle time, try to reinforce positive behaviors,” Rosa said.

The Youth Violence Reduction Initiative is the Philadelphia school district’s latest attempt to secure safer futures for the teens most at risk of engaging in violence. The one-school pilot is Philadelphia’s version of the national Comprehensive Gang Model, a set of strategies used in other cities that include one-on-one mentoring, group counseling sessions, tutoring, and — when needed — law enforcement supervision.

The initiative doesn’t provide direct services such as counseling or tutoring, but instead students are referred to community-based organizations.

The effort began about a year ago with $1 million in federal funding, and district leaders say it’s Philadelphia’s first formal, evidence-based violence reduction initiative inside a school. If it succeeds, the initiative could redefine safety on the city’s highest-risk campuses.

Although the city’s homicide rate has fallen so far this year compared to 2022, violence is an ongoing and urgent issue in Philadelphia, including for its young people. About 10% of the more than 1,500 victims of fatal and non-fatal shootings in 2023 were under the age of 18, according to the city’s latest data.

During the 2022-23 school year, 199 students were shot in Philadelphia, and 33 of those shootings were fatal, according to the school district. Twelve Bartram High students have been victims of gun violence since the start of the 2020 school year, the district said.

The school district has tried to prevent shootings by placing police officers in neighborhoods near schools, deploying monitors on campus perimeters, and launching conflict resolution programs. But the violence reduction pilot Rosa works in represents a different approach.

“Before we were sitting on the perimeter, now we’re looking at something extremely proactive,” said Kevin Bethel, the district’s former school safety chief, who now serves as Mayor Cherelle Parker’s police commissioner.

Student-involved shootings and incidents of students carrying guns are some of the situations project staff are looking at. But they’re also focusing on fights that occur between groups of students who are in conflict with one another. The district says the initiative aims to reduce violence in general, not just gun violence.

“One of our outcomes is gun violence, but I wouldn’t say that’s what we do,” said project director Brandy Blasko. “It’s violence in general.”

The pilot is staffed by Rosa, two case managers, a full-time research assistant, and a project director from the Office of School Safety.

While students like Travis are identified by the district as being at risk for involvement in violence, he chose to join — no students are placed there, nor are they required to join. Instead, it’s an option for those who feel they’re at risk and want extra mentorship and support. Although all the students in the initiative at Bartram High are male, female students can also participate.

Jerome, a 16-year-old Bartram student in the pilot, said the district has a role in keeping kids safe from violence. He said that a large number of his peers are carrying guns and will start conflicts with one another just because they want to.

“I don’t feel safe until I get in the house,” Jerome said.

Jerome came to Bartram from a different high school, where he said he was involved in multiple group fights. He said if not for the Bartram High program, he’d still be making “bad decisions” and would have been kicked out of school.

Helping students say no to violence

The U.S Department of Justice developed the Comprehensive Gang Model in the 1990s for use in communities as well as detention facilities. The Youth Violence Reduction Initiative is the Philadelphia school district version of that model; project leaders renamed it because many Philly teens don’t consider themselves gang members.

“To label our youth as gang kids, it’s just not a good idea,” Blasko said. “They’re just kids who just need some direction.”

In a community setting, the model involves a combination of city lawmakers, concerned community members, and law enforcement representatives according to Celeste Wojtalewicz, research associate with the U.S. Department of Justice’s National Gang Center.

“It makes sense to me that a school district could do this right with a combination of principals and teachers and counselors ‚and perhaps parents and also law enforcement, " she said. “School is everyone’s responsibility, and that’s the biggest piece.”

However, the Community Gang Model showed no statistically significant impacts in five pilot cities, according to a 2022 Urban Institute analysis that measured arrest rates and overall violent crime. A 2015 study from Suffolk University did find the model was associated with fewer youth arrests and smaller increases in homicides.

Jeffrey Butts, director of the research and evaluation center at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City, said programs that focus on students only tackle a portion of a community’s overall violent crime problem. He also said that schools receiving grant money for violence prevention sometimes just use it to roll out interventions without studying them.

“Essentially the problem with the whole field is research and evaluation,” he said. “I don’t know if the school system is set up to test the effectiveness of their approaches.”

Blasko is tracking the program over the next three years based on 49 performance measures with help from a full-time research assistant hired by the district. Officials plan to release one-year outcome data this month, including updates on student-involved gun violence around the school and among students in the initiative.

Butts says there would have to be intensive study on the schools and neighborhoods surrounding Bartram to prove that the Youth Violence Reduction Initiative changed trends in crime.

The Bartram High pilot involves a multidisciplinary team of counselors, psychologists, and external community partners. That team meets weekly to discuss individual student cases and any serious incidents of violence.

Also at that meeting are representatives from the Penn Community Violence Prevention Team, which handles conflicts in the neighborhoods surrounding Bartram High. They also monitor students who were in the pilot after they graduate from school.

The prevention team’s strategy focuses on decreasing impulsive behavior by talking to people about making better choices, said program manager Denise Johnson. She and her colleagues try to learn everything they can about someone’s situation — what their home life is like, how much access they have to guns — so they can offer resources such as family counseling or housing and employment assistance.

“School programs are great, but they only work with the individual during school hours,” Johnson said. “It’s a lot that goes on between 3:30 or 4 to the next morning.”

Rosa and his team sometimes have to look beyond their own resources to stem violence. For example, if a student tells him they’ve been threatened, especially if there’s a gun involved in the threat, he has to activate the Threat Assessment Protocol.

That’s a district-wide policy officials developed two years ago with help from the U.S. Secret Service and the University of Virginia. If a student in the violence reduction initiative receives a threat involving a gun, two Threat Assessment Liaisons will speak with the student who was threatened, try to identify whoever made the threat, and request support from police as needed.

“Sometimes we’re going to the home to see if a child has a gun and making sure they don’t have a gun,” Bethel said. “In some of the very few cases we will make an arrest because we find that it has been confirmed, we’ve identified a threat and we’ve seen it’s actionable.”

Bartram staff also call in community organizations to resolve specific conflicts. For example, Rosa noticed an uptick in fights between female students last school year and went to a Philadelphia organization called Conscious Queens that specializes in boosting girls’ self-esteem.

“Sometimes they get lost on the shuffle because they’re not the ones doing the overt violence,” Rosa said. “But they’re definitely involved with carrying guns, they’re in the car with people, stealing cars. … So we’re hoping to kinda tackle some of that.”

The Youth Violence Reduction Initiative will continue at Bartram under the current grant until October 2025. The district has already received funding from the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency to expand it to a second school beginning in the fall.

The district aims to find additional funding to do a longitudinal study of the violence reduction initiative’s participants over six or seven years.

Travis, the 17-year-old student, hopes to be a working electrician by then. Jerome wants to run his own Airbnb business.

“If this program was in every school, it would just help everybody see the bigger picture,” Travis said.

He said Rosa taught him how to calm down, control his temper, and focus on schoolwork.

“He gave me motivation to do my work,” Jerome said. “At one point I didn’t believe in myself, and he believed me.”

Correction, Jan. 12, 2024: This article has been updated to correct that the initiative doesn’t provide direct services to students but refers them to community-based organizations. A previous version of this article said the district didn’t provide the services. Additionally, the district has hired a research assistant to track the program. A previous version stated the district had hired a research analyst.