About this series: Four years ago, Chalkbeat reporters documented the stories of high school freshmen experiencing a critical year through Zoom calls and from behind masks. These students, who experienced freshman year at a distance, are now graduating seniors. How did the pandemic shape their high school lives? How did their expectations for these formative four years play out? We caught up with these members of the Class of 2024 to find out.

Four years ago, Yahya Long was preparing to go back to school after a near lifetime of learning at home. He hadn’t been in school since one brief, miserable experience in third grade.

But then the pandemic hit, disrupting his plans. He had to wait even longer to do in-person learning at a school he and his mother felt was a perfect fit for him: Workshop School, a quirky place that started out as the automotive academy of West Philadelphia High.

Ninth grade at Workshop was remote – a disappointing experience not only because it delayed his being with peers, but because Workshop stressed hands-on, project-based learning, which was hard to do on Zoom.

At Workshop, Long looked forward to indulging his love of animation and other self-directed, creative pursuits, as well as catching up on his socialization skills, which he admitted were rusty.

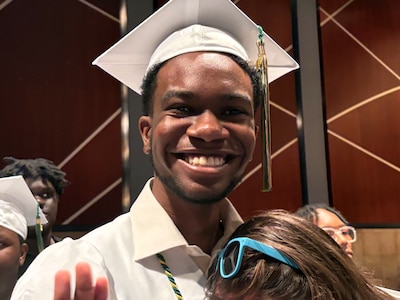

But on Thursday in his speech to his classmates and their families as salutatorian of Workshop’s 36-member Class of 2024, he said graduation was a “momentous occasion” preceded by trials and tribulations.

“Our journey to get to this position in our lives was a rocky road to say the least,” he said. “From practically having our freshman year ripped from us because of COVID, and then being forced to adjust.”

Long plans to continue his education at Arcadia University, located just outside the city limits in Elkins Park, and study art and animation.

His speech was witty and self-revelatory. “These four – really three – years of my life have been pretty monumental to my development,” he said. “I remember in the 10th grade being a shy weirdo in the corner who kept to himself and made sure he wasn’t noticed, which I think I failed at miserably.”

Workshop helped him evolve, he said, “to a weirdo who is slightly less shy and willing to speak in front of a crowd of people, pretty crazy if you ask me.”

Now 18, Long has blossomed. At first, he said, going to school in person was just “something to do, a reason to get out of the house.” But attending Workshop in person for three years gave him structure and the chance to interact with peers. Teachers encouraged his creativity and interests.

At first, he said in an earlier interview, he found interaction with other students and teachers to be difficult.

“I wasn’t that outgoing and talkative. I was not antisocial, just shy.”

But he adapted well. Although Workshop started out as an automotive academy, and many in the mostly male student body do prepare for careers as mechanics, Long wasn’t one of them.

“I think I put on a car tire once, that’s the most I did,” he said, laughing.

Instead, he spent his time making art. In 11th grade, he was an intern for a semester at the University City Arts League, where he discovered the Fabric Workshop. “Screen printing, working with textiles, that seemed chill,” he said.

As a career, he said, “I want to do art. I want art to give people experiences, to make them feel good, to have a positive experience of the things I make, to say, ‘Whoa, that’s cool.”

Frogs often show up in his artwork – as a child, he learned to read with the book Frog and Toad. In his typically taciturn way, he shrugged when asked to elaborate on this attachment beyond his first exposure through that book.

“I don’t have a deep answer, I just like frogs,” he said. “I just like how they look.”

To hear him tell it, his artwork reflects whatever is preoccupying him at the moment, from “circles to robots to ordinary people.” One storyline that he has explored is “a big robot that goes to different planets across the galaxy.”

He also has done animation of a Spider-Man-like character flying and tumbling through the air.

As an animator, he would like to have his own company. “If the opportunity arose to work for Disney or Pixar or game companies, that would be cool. But I really want my own control over things I want to make.”

He is not, by his own admission, “a person who wants to change the world or be president. I want to make it, while you’re here, that you have a good time.”

Initially, Principal Ayanna Walker told Long that he would be the school’s valedictorian, and his reaction was matter-of-fact, she said. “It was not that he was almost mad, but more like, ‘Oh, now, I have to give a speech.’”

But just the day before graduation, when final grades were calculated, it turned out that he was salutatorian. With a 3.8 grade point average, he fell a tiny fraction behind Johari Williams.

He also took this news in stride. “He’s comfortable with who he is,” Walker said, “and he doesn’t need the validation. It’s not too often that you know who a child is at an early age. He’s one of those people true to their identity … his own person … you never see him with a crowd … he’s talented, artistic and smart.”

A school with a special mission

The initiative that became Workshop started in 1999 at West Philadelphia High School as an after-school program to build electric cars, founded by teacher Simon Hauger and several other educators. By 2012, it had evolved into its own separate school with a focus that moved beyond its automotive roots to focus on hands-on projects of all kinds.

“Our school is not for kids who want to be a doctor or lawyer and go to Harvard,” Walker said. Many of its students “don’t fit in at a typical school. This school is not cookie cutter.”

Since it had such a specialized mission, it benefited from the district’s longtime high school admissions process – it has tiers of selective and citywide schools, all with criteria for entry – that gave principals a say in choosing the student body.

But in an effort to combat any bias and to open opportunities for more students to attend the city’s most selective magnets, especially Masterman and Central, district leaders inaugurated a lottery three years ago that gave preference to qualified students from five underrepresented ZIP codes. This system took away any principal discretion in selecting the incoming class.

The new process has proven to be problematic for schools like Workshop that cater to a particular type of student.

“It’s had huge implications,” said Hauger, who left as principal several years ago. “We serve some of the most marginalized students in the city.”

Workshop leaders had worked hard to give more balance to the student body and to make sure those admitted understood what the school would demand of them before deciding to attend. The lottery upended those efforts and has resulted in many students going there who are not a good fit for the school, Hauger said. There also has been a surge in students with special needs. Its enrollment is now below 200.

For Long, however, who entered just before the lottery took effect, Workshop has served him well. For his final projects at Workshop, he made a website and put together an art portfolio.

“I just want to say I have the utmost faith in all of you to be successful people in your lives, even if you yourself don’t believe so,” he told his classmates, citing how the projects they did and the people they met taught them about networking, about finance, and about their field of interest.

“Everything will go according to plan, all you have to do is just work for it,” he said. “And finally, let us all raise our heads up high and march across the line into the unknown and embrace the trials and tribulations that await us.”

Grinning broadly, he ended with a joke that hinted at how nervous he was. Now, he said, “I am going to take a nap or something.”

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.