Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

Brittney Whitehead, assistant principal of the small, innovative high school in Northwest Philadelphia called Building 21, came to the Philadelphia School District’s educator hiring fair last Friday with one goal: She wanted to recruit certified special education teachers.

But Whitehead left disappointed.

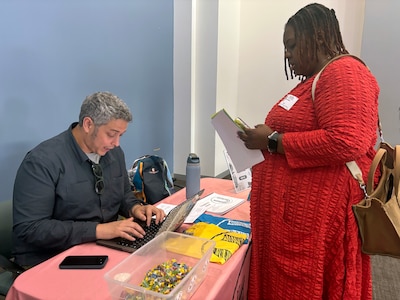

At the end of the two-hour event, held at the district’s headquarters at 440 North Broad Street, she had only found one possible candidate for those positions.

“I thought that this Grow your Own pipeline … would have made a lot more of a variety of people, but we didn’t really have many,” she said, referring to a district program that supports paraprofessionals to get full teaching certification.

“You can definitely feel the impact of a teacher shortage and on top of that a special ed teacher shortage,” she said.

As of now, the district needs to fill at least 452 vacancies among its nearly 9,000 teaching and counseling positions before school starts at the end of August, according to a list distributed to attendees at the hiring fair. But it is always a struggle to fill all available jobs – and the problem is getting worse. There have been more than 400 vacancies reported in each of the last two years, meaning that in any given year, thousands of students could face a revolving door of substitutes during crucial times in their development.

And by far, the biggest shortage is among special education teachers. Of the 452 vacancies, about 150 were special ed. That’s one-third of the total.

“Nobody can find enough special education teachers,” said Edward Fuller, a professor of educational studies at Pennsylvania State University who researches the teaching profession. “It’s staggering how bad the situation in special ed is.”

And the vacancies now don’t fully account for the high rate of teachers who leave, many after the school year starts. Fuller’s latest report found that 13% of district teachers quit their jobs in 2022.

While not limited to Philadelphia, he said, the shortages are most acute in high-poverty districts with majority Black and Hispanic students. Schools are also struggling to find teachers of English language learners, he said.

“There are no more vulnerable child populations than these two, and that’s where our vacancy rates are highest,” Fuller said. “This should not be acceptable.”

Thousands of Philly students go without a permanent, certified teacher

As a rule, Philadelphia fills 98 to 99% of its teaching positions in any given year, said Amanda Mitchell of the district’s educator recruitment team. While that sounds high, it still can leave thousands of students without a permanent, certified teacher.

In 2022, the district started the school year with some 200 vacancies. Last year, the number was nearly twice that, with just a 95% “fill rate” weeks before school started.

Of the 200 people who registered for last week’s event, 149 showed up, said Mitchell. They included teachers who are new to the profession, teachers with experience elsewhere, and current district teachers seeking a new assignment.

The number of people graduating with teaching certificates in Pennsylvania has declined 67% over the last decade, Fuller said. And many people are working in schools with emergency certifications.

Under those certifications, people have a bachelor’s degree but not a teaching degree, or have a teaching degree in an unrelated field. They have three years to earn the proper credentials.

In the meantime, they have to prove that they are enrolled in a certification program. Sometimes, though, the person leaves before the three years are up, a scenario that essentially perpetuates the use of non-certified teachers.

Fuller said that, based on his latest research, 24.4% of teachers in Philadelphia have emergency certification – compared to less than 3% in Bucks, Montgomery, and Chester counties. In Delaware County, which includes Chester-Upland and William Penn, it is 8.5%.

At the hiring event, applicants could speak to representatives from 70 of the Philadelphia district’s more than 200 schools, each of which advertised the positions they needed to fill.

A growing number of students with special needs

For the past year, Neil Geyette, principal of The U School, which he founded in 2014 to serve marginalized students, said he had to hire a teacher for an emotional support class through an outside recruiting firm. Many people who wind up in the district under these circumstances come from related fields, such as social work, and have experience working with children – but not as teachers.

The person had an emergency certification, and he worried that she wouldn’t be able to handle it. But, he added, “she did a great job.”

That isn’t always the case. And as Fuller’s numbers show, city schools are increasingly relying on emergency certifications to fill all their jobs, especially in special education, said principals and others who sat at tables waiting for potential recruits to stop by.

Emergency certification “is starting to become the norm,” said Whitehead. “It’s harder to find people who have traditional education backgrounds not under emergency cert or that have been in education for longer than three years.”

Complicating matters is that in some schools, and especially since the pandemic, the special education population is soaring. Geyette said up to 36% of the students in his school receive special education services, compared to a districtwide rate of 19%. That figure is also trending upward; as recently as 2020-21, it was 17.4%.

Geyette said he found one or two potential hires at last week’s event.

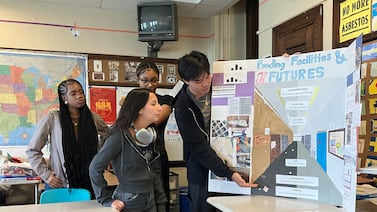

“More students have been identified as special education since the pandemic,” said Ayanna Walker, principal of the Workshop School, which has a project-based curriculum and, like Building 21 and the U School, was created for students seeking alternatives to large, neighborhood high schools. She said that at Workshop, if all the prospective ninth graders who have signed up actually enroll, the special education rate next year will be 47% – nearly half the student body.

Some eager teachers can’t find positions

While attendees at the hiring fair who were certified in special education had dozens of choices, teachers trained in other fields found their options limited. After special education, the next biggest category to fill was for elementary teachers, with around 100 openings at schools with grades kindergarten through sixth.

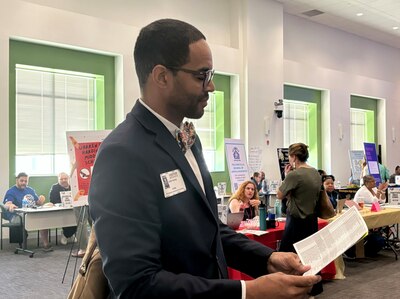

But for some teaching categories, there are very few openings, as Justin Avery learned. Avery is certified to teach social studies – not a high-demand field. Of all the vacancies on the district’s list, less than a dozen specified social studies.

Fewer than 2% of teachers nationwide are Black males – the number is closer to 5% in Philadelphia – but Avery has been out of work for a year after being laid off due to budget cuts in his previous district in South Jersey. He has two master’s degrees and 18 years of experience.

“I guess I’m overqualified,” he said.

But after talking to representatives from several schools at the event, he thinks he might have a chance of picking up a position as a writing teacher.

He’s hopeful. Still, he said, “It’s been a challenge.”

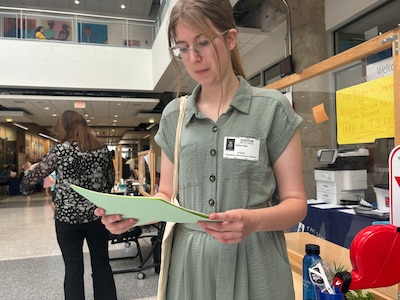

As a student-teacher while getting her master’s degree in music education from University of the Arts, vocalist Chloe Pyle she experienced two extremes of city education: Friends Select – small, Quaker, private, and in Center City; and Frankford High – big, old, in a gritty neighborhood and forced to temporarily relocate most students due to asbestos problems.

She fell in love with Frankford.

“It was so different from my own high school,” said Pyle, who grew up in rural Delaware. “It completely changed how I viewed education. Some of those kids live lives that the kids in the other school would never understand.”

Backstories aside, she said, “they were all just students in music class.”

Whitehead, from Building 21, said more than 40% of their students have Individualized Education Programs, and that the school has increased its special education staff from four to nine teachers, and there are still two vacancies.

At the end of the event, educators like Whitehead often didn’t have many more options than when they started. She interviewed several career-changers, she said, including a former banker who wanted to teach English learners. But that was one need her school doesn’t have.

Stll, Whitehead noted, the shortage is palpable and whether candidates are new to the profession on emergency certification or seasoned veterans with the right credentials, “they’re all needed.”

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.

Azia Ross is a summer intern for Chalkbeat Philadelphia. You can reach her at aziaross@chalkbeat.org.