Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

Efforts to improve Philadelphia students’ reading skills aren’t confined to classrooms. One of the latest such campaigns to bolster literacy is Right2ReadPhilly — and it relies on a tool rooted in Black history.

The campaign began in early June and is run by Mighty Engine, a local creative agency. The group is building access to reading resources and sign language for children as young as six months old. It works hand in hand with many other groups — including the city’s “reading captains” — that are united in the pursuit of getting Philly kids to read as early and often as possible.

“We know families can play a crucial role in turning around our city’s early-learning crisis, furthering recent early literacy gains. But [if only] we could grab their attention with fun, free, proven things that they can do together with their children,” Heseung Song, CEO of Mighty Engine, said in a statement. “The campaign was designed to prove this is possible.”

The backdrop for this work is the school district’s shift to a new English language arts curriculum for the upcoming school year. It will use teaching techniques and materials based on the science of reading and world knowledge. Education officials and advocates hope this change will positively affect outcomes: While students’ scores on last year’s state tests in English language arts improved in some respects, just 34% of students in grades 3-8 achieved proficiency, and fewer than one-third of third graders reached this benchmark.

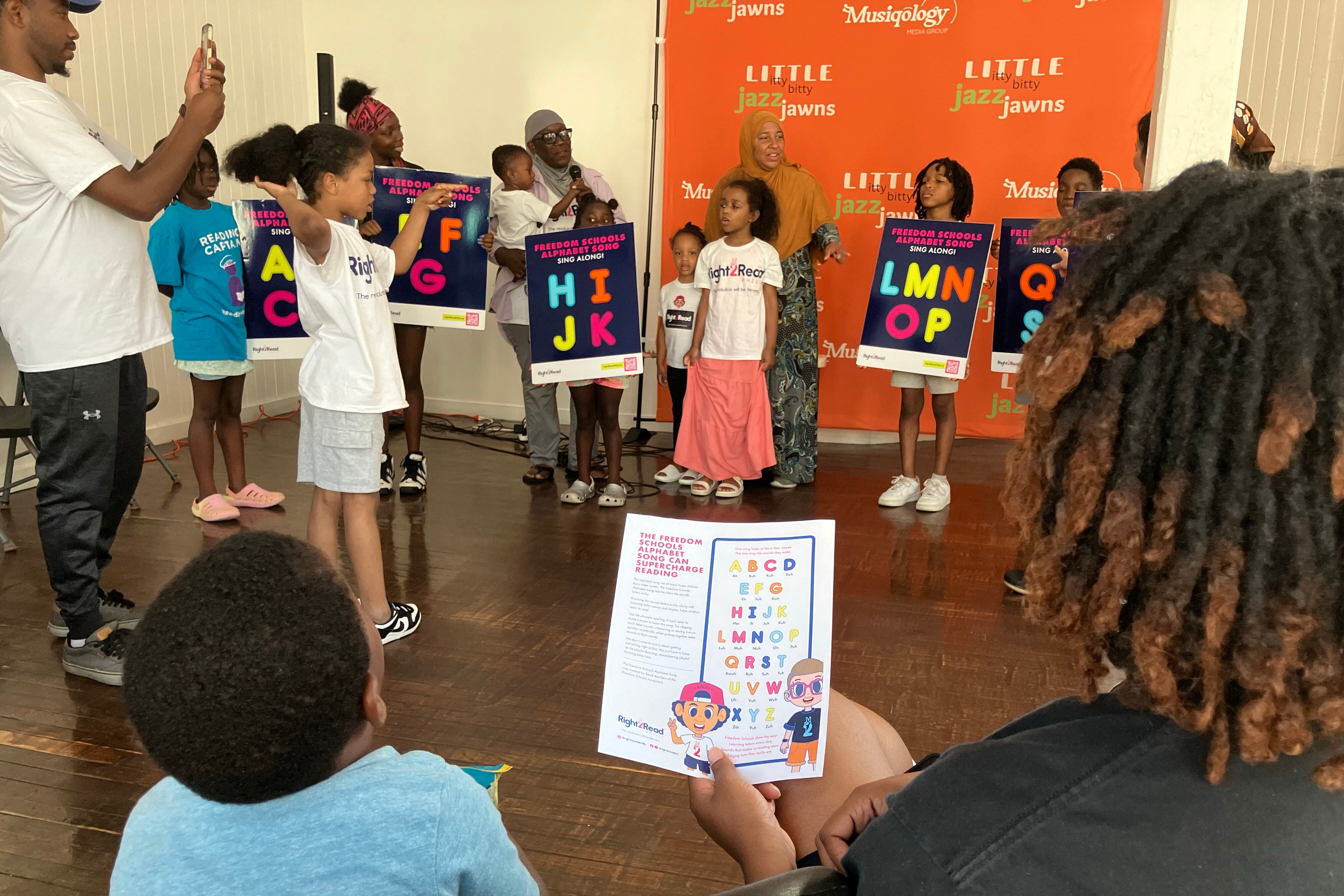

Although it officially started in June, Right2Read has been hosting small neighborhood events in the city for months, according to a spokesperson. Among other strategies, it has been teaching families the “Alphabet Song” that was taught in Freedom Schools, as well as “simple signs,” which are American Sign Language phrases for young learners.

Although the song’s tune comes from the widely known “I Don’t Know, But I’ve Been Told” melody, it encourages children to say the sound a letter will make — “ah” for A, “buh” for B, “kuhh” for C — instead of just its name. This phonics-centric method forces children to learn the sounds of letters rather than only memorizing the names and orders of letters.

The “Alphabet Song” originated from Freedom Schools, which became popular in the 1960s as a way to provide Black families not just an education, but social, political, and economic liberation as well. Those schools were part of a long line of efforts to educate Black children, including clandestine schools for enslaved Africans.

Sharif El-Mekki, CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development in Philadelphia, said the “Alphabet Song” is linked to reading techniques he remembers learning as a kid in West Philly and that people sang it on porches in his neighborhood.

The song “was a part of this comprehensive pedagogical framework to teach young black children how to read,” El-Mekki said. “Not only were we learning this alphabet song, we were learning: What does it mean to put these blends of sounds together?”

The song resonates with people doing similar literacy work in the city. Elaine Wells, who is a reading captain in Philadelphia and founder of Tiny Trekkers, a local trail and nature group for children, said her 7-year-old granddaughter struggled to learn to read.

“She could recognize ‘oh that’s an A or that’s a D’ but in trying to put the letters together to make a word, she definitely struggled,” Wells said.

But after she learned the song, according to Wells, “She has just been adamant about reading any and everything that she can and she’s been reading so much better.”

Building that kind of phonics-based foundation is crucial, said Marie Clarke, a third grade teacher at Philly’s Henry C. Lea Elementary, even though it’s not the only approach children can lean on to improve their reading skills.

“Context clues will help, that’s a strategy, but they still need the foundation of doing their sounds,” Clarke said.

Right2Read encourages people to put their own creative twists on the “Alphabet Song,” as long as such remixes still teach letter sounds (and are appropriate for all audiences). It even encourages doing double dutch while singing the song. And there are even prizes on offer.

The group takes a multi-faceted approach to helping children’s language skills as early as possible. Right2Read encourages teaching American Sign Language’s simple signs to young learners because doing so “can boost overall language capacity, including speech, and early learning,” according to its website.

“I think it’s important for children to feel both connection to their caregivers as well as confidence to express their wants and needs as early as possible,” said Sara Novic, author and consultant for Right2Read’s sign language component.

In addition, the organization’s website connects families to everything from ways to get free books, to how to incorporate “playful learning” in everyday urban settings.

The group’s impact is on track to stretch well beyond literacy and instructional circles.

Wells said she’s going to go over the “Alphabet Song” at every Tiny Trekker event. That way, she said, she can help instill it “as an easier way not just to recognize what the letter name is but what the sound is.”

Correction, July 26, 2024: This article has been corrected to reflect that Mighty Engine is a local creative agency. It has also been corrected to include the name of Right2ReadPhilly, the spelling of the name of Mighty Engine’s CEO, and the melodic basis for the “Alphabet Song.”

Azia Ross is a summer intern for Chalkbeat Philadelphia. You can reach her at aziaross@chalkbeat.org.