Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

Kristyn Kahahaloe still remembers a little boy from her class in a New Jersey early learning center when she was a rookie teacher starting students on their journey to becoming readers.

The boy, who was in kindergarten, “just couldn’t figure it out the way I was teaching it,” she said. “This bright blossoming flower kept shrinking and shriveling, and I didn’t know what to do.”

Despite her years of teacher education, Kahahaloe, now a kindergarten teacher at the John Hancock Elementary School in Philadelphia, concluded that “my lack of knowledge was why he was not learning how to read.”

For decades, disputes over how best to teach students to read has divided teachers, scholars, and policymakers. Was the answer phonics or “whole language”? What about “balanced literacy” versus “structured literacy”? New terms like “phonemic awareness” and “foundational skills” entered the vocabulary, but didn’t settle the debate.

Like their colleagues nationwide, Philadelphia teachers were buffeted about by the debates. Many received scant training in their teacher preparation programs in explicit reading instruction. And once in the classroom, they were often left with a hodgepodge of materials and resorting to “doing what they think is best,” as Kahahaloe put it.

That is about to change. For the upcoming school year, the Philadelphia school district is putting into practice a new reading curriculum as part of a $70 million investment in updated instructional materials in English Language Arts, math, and science. The early grades language arts curriculum from EL Education replaces a teacher-driven one, and is grounded in the science of reading, the now-accepted consensus on what works best for literacy instruction. Given what recent test scores say about reading skills in district schools — and classrooms nationwide — such an intervention could make a big difference in school and beyond.

“There is no question at this point that the science of reading is the way to teach students to read,” said Nancy Scharff, a literacy expert and professor at St. Joseph’s University and a consultant with Read by 4th, the Philadelphia-based campaign to have all children read proficiently by the time they enter fourth grade.

But adopting a curriculum that matches best practices doesn’t guarantee it will succeed in classrooms. There are concerns about whether teachers have been sufficiently prepared to use it, and the district cautions that it will take some time for educators and students to see results.

‘More continuity for teachers and for kids’

The “science of reading” is built around a five-pronged approach — phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension — that is based on research on how the human brain works.

Concerns about how reading is taught and low reading scores have spurred many states to pass laws recently mandating what approach and curriculum their schools should use, with the science of reading often at the foundation of such statutes.

The Pennsylvania legislature considered putting provisions in its 2024-25 budget requiring districts to adopt the science of reading approach, with mandated teacher training and sophisticated testing of students to detect learning differences. But those provisions — estimated to add nearly $70 million to the budget next year— were cut from the final bill.

For the past several years in Philadelphia, the district had been adhering to a curriculum that was created in-house by teachers themselves. But it often lacked sufficient materials to go with it. Many teachers were stressed out trying to find the right books to use.

“I think this will allow for a lot more continuity for teachers and for kids,” said Meredith Mehra, the district’s deputy chief of teaching and learning. “A lot more resources are embedded that will take the pressure away from teachers to create them.” Teachers “can think more about the kids in front of me than what text I am going to use.”

Just 34% of students in grades 3-8 achieved proficiency on the Pennsylvania reading tests last year, although scores did improve in some respects in 2023.

Research shows that being a proficient reader by fourth grade makes a huge difference in future life outcomes. Yet state test scores show that 71% of city fourth graders are not reading at grade level, notes Read by 4th. And half the city’s adult population is functionally illiterate, according to federal data estimates.

Jennie Bogoni, executive director of Read by 4th, said she sees the new curriculum as a step forward because it will standardize instruction across the district and is grounded in the science of reading.

She also cited a federal report from earlier this year that Philadelphia has been ahead of most other urban districts in making up pandemic-driven learning loss in reading and math.

“The district has made incredible progress bouncing back from the pandemic, and this curriculum should accelerate this change,” she said.

Scharff said that the new EL Education curriculum equips all teachers with the tools “to make sure children learn to read, emphasizing what we call foundational skills.” They include not just instruction in decoding, phonics, and phonemic awareness, but the development of background knowledge.

“If a student can decode a word competently but doesn’t know what it means, it doesn’t matter. Background knowledge needs to be part of the program. This curriculum does that effectively,” she said.

She noted that many children in Philadelphia come to kindergarten without much exposure to books — although many groups are working on access to reading resources — and so lack a strong knowledge base: “The best thing is to teach them to read so they can broaden their knowledge base … .the ‘science of reading’ is not just phonics.”

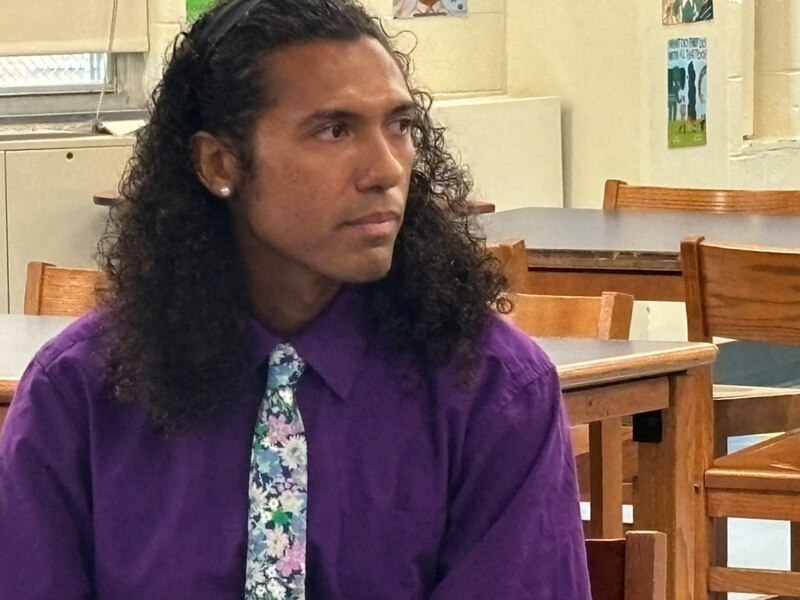

Third grade teacher K.P. Edwards said has been reviewing the curriculum on his own over the summer and hoped that it will make his job a little easier. Students come to him with a wide range of skills; in one class, he said, he had a girl reading at a seventh grade level and another who could barely recognize letters.

“I am cautiously optimistic,” he said.

Science of reading curriculum isn’t a cure-all

Scharff noted that while a new curriculum that covers all the right bases is helpful, it is not a magic bullet. “It is going to take time for teachers to be comfortable with it, learn it, and become adept at using the new materials,” she said. “We have to be very careful about looking for instant gratification.”

Laura Boyce of Teach Plus, which works to recruit teachers to Philadelphia, is a bit more skeptical.

“Things have gotten polarized in the science of reading debate,” said Boyce. If educators only focus on phonics and don’t develop skills around building content knowledge and vocabulary, “that’s a problem,” she said. So is an approach that assumes students will deduce words from pictures and other cues and downplays explicit phonics instruction, she said.

Boyce is also concerned about whether teachers have been adequately prepared to use the new curriculum: ”From what I’ve seen so far, there’s no evidence of a super strong plan for teacher development.”

The district held a week-long training session earlier this summer that was attended by about 400 teachers, and is planning more professional development in the weeks before school starts after they start teaching. They also plan ongoing teacher coaching throughout the school year.

Mehra estimated that “it will take a whole year’ for teachers to become comfortable with the curriculum and see results. “It’s unfair to teachers to expect more than that,” she said.

Edwards, who teaches third grade at Muñoz-Marín Elementary School in Kensington, where all of the students in his school were from economically disadvantaged families and nearly 90% were Latino, many with limited English skills, the school’s demographic data from last year showed.

“I’m lucky, I’ve had a school based coach who helped me develop strategies for teaching literacy,” he said. Those strategies relied on many of the principles embedded in the new curriculum, including explicit phonics teaching.

“I’m hopeful,” he added. “With that model we had some gains. I’m hopeful next year we will have actual workbooks and more resources.”

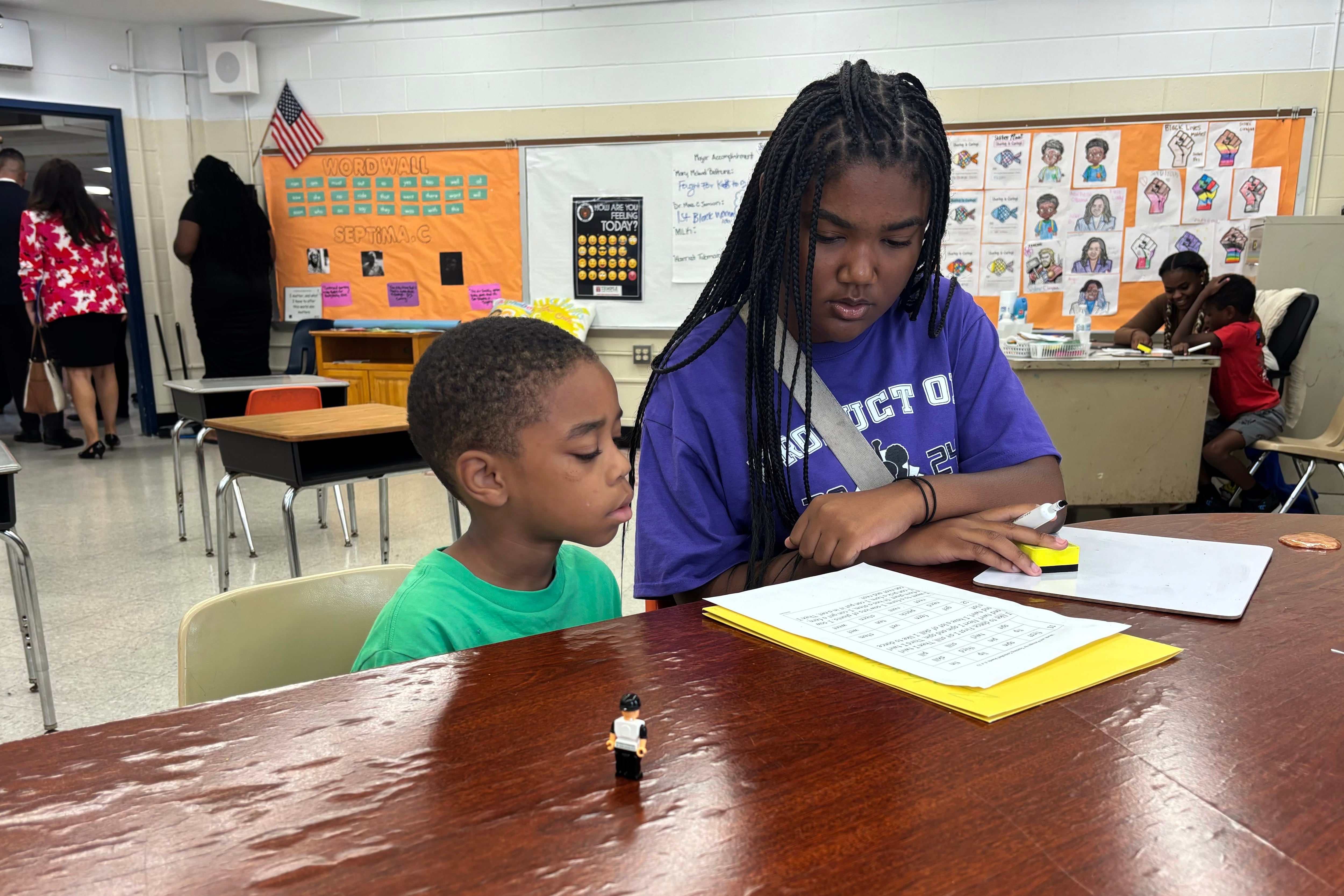

Kahahaloe’s difficult experience with the boy who wasn’t responding to any of her efforts motivated her to find the proper training for teaching reading.

She enrolled at Fairleigh Dickinson University in north New Jersey to learn the Orton-Gillingham approach to reading instruction, which was designed for students with dyslexia but which can work for all children.

She thinks the new curriculum will help. But for her, the people in the classroom will be the decisive factor for whether it works.

“A curriculum doesn’t teach kids, teachers teach kids,” she said.

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.