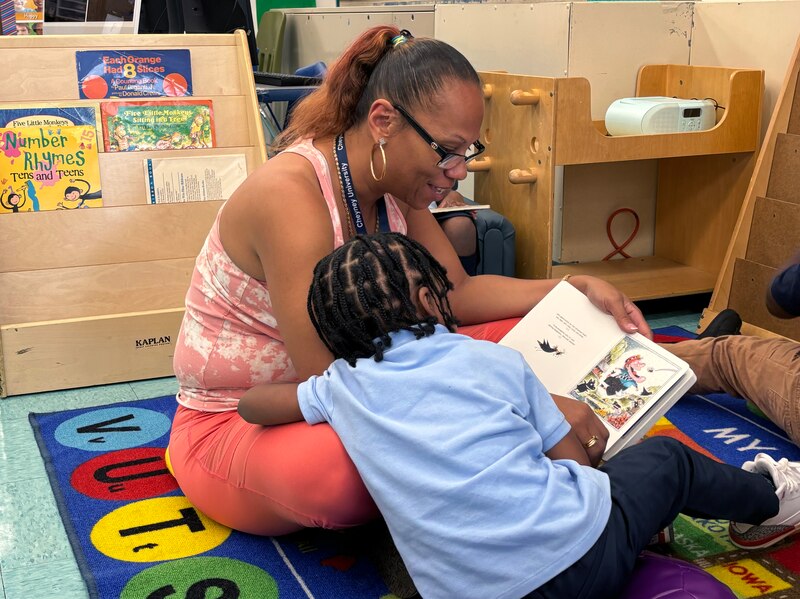

Throughout the 2024-25 school year, Chalkbeat Philadelphia will follow a new teacher, Kahn-Tineta Smith, as she adapts to the joys and challenges of working in the city school district. This is the first of several periodic check-ins we hope will shine a light on the state of the Philadelphia teaching workforce.

Kahn-Tineta Smith was facing a crisis. The little girl with the carefully braided hair didn’t like the color of her magic marker and was making her displeasure known.

It was time for a hug.

Another little girl threw her marker down.

“We draw with our markers, we don’t play with them,” Smith said gently.

It was her second day teaching preschool at the Mary McLeod Bethune Elementary School in North Philadelphia, and the culmination of a lifelong dream. At age 52, after two decades working in city schools as a paraprofessional, she is now a full-fledged teacher. Smith works with 10 3- and 4-year olds, a number that could soon grow as parents continue to register their children.

“Now I’m still all over the place,” Smith said during a respite from her activity-filled morning, “but once I get the curriculum down, I will keep them engaged.”

She smiled. “I’m so tired.”

But she loves it. She dreamed of doing this job for nearly half a century, even as she found work in fast food to help support her three children.

Smith is one of 75 paraprofessionals who have made the transition to teaching this year as part of a district initiative called Para Pathway that started in 2022. With $2.5 million in federal pandemic aid supplemented by $1.7 million district funds, Para Pathway has trained more than 100 paraprofessionals for teaching careers by helping them earn associate and bachelor’s degrees.

Para Pathway is far from a luxury, because Philadelphia is fighting a teacher shortage. The district is starting at least its third straight school year with hundreds of classroom teacher vacancies. The number of graduates from Pennsylvania’s teacher education programs has plummeted 71% over the last decade, reducing the pool of available teachers.

To help deal with the shortage, the district created Para Pathway for its 2,500 paraprofessionals like Smith who work as teacher aides and classroom assistants. Besides helping in classrooms, they may do some tutoring, patrol the hallway, keep order on the playground, and supervise after-school programs.

Smith’s time as a paraprofessional in the school district was spent mostly at Bartram High School, starting in 2004. She earned her teaching degree in early childhood education earlier this year from Cheyney University, one of five higher education institutions that participate in Para Pathway.

Bethune Principal Aliya Catanch-Bradley said in filling out the faculty this year, she and her team deliberately tapped Smith and one other Para Pathway graduate, even though “we had other options.” While the district started the year with 347 teacher vacancies, according to Superintendent Tony Watlington, Bethune is fully staffed, the principal said.

“These are pillars of the community and role models for our children” as well as mentors to current paraprofessionals who might want to follow in their footsteps, Catanch-Bradley said.

Even with Para Pathway, finding a teaching job took a bit of serendipity for Smith. At a district hiring fair earlier this year, she went from table to table looking for a school that needed an early childhood teacher.

She didn’t get much interest until she stopped at Bethune’s table. Catanch-Bradley and Bethune Assistant Principal Yasmin Evangelista “were so welcoming,” she recalled.

“I filled out the paperwork right there and was hired,” she said.

Dreaming of being a teacher while working at McDonald’s

For Smith, Para Pathway was the answer to a prayer. She can’t remember a time when she didn’t want to be a teacher.

Growing up in Southwest Philadelphia, she said, she would conduct classes for little cousins and other children in the area. “I had a school in my house,” she said. “I gravitated to being an educator; I knew that was my calling on this earth.”

She also wanted to be a role model. Smith describes herself “from the neighborhood” and acutely aware of what children need to thrive. “When I was in school, I had many teachers help me,” she explained, “and that’s what I wanted, to give back to others, to be a positive entity for young people.”

Plus, she said, “I was my children’s first teacher.”

Smith was raised by her mother and grandparents. Her mother moved around so much when she was a child that one year, she had to repeat a grade due to so many absences. But later, her family signed her up as a student to be part of the school district’s voluntary desegregation program, meaning that she traveled to Northeast Philadelphia by bus for grades 7-12.

When she graduated from George Washington High School in 1991, she had an eight-month-old daughter. After the ceremony, she recalled, she took off her mortarboard and put it on her baby’s head.

“Mommy graduated,” she told the child.

But going directly to college was not an option. And over the next 12 years, Smith had two more children, raising them mostly by herself. “Life happened,” she said.

When her children were young, she always worked at places like McDonald’s to support them. “I was raising my kids, and I always had a job,” she said.

Still, Smith found time to help her community. In the early 2000s, she participated in a program called the National School and Community Corps, a program run by City Year that provides help to “struggling schools that needed extra people.” At Harrity Elementary School, she tutored and helped with after-school and summer programs.

The City Year experience, she said, opened her eyes and started her on the road to being a teacher: “I saw how the schools were running, what children were lacking academically and socially. That piqued my interest more.”

Smith applied to be a teacher’s aide. In 2004, after three years of subbing in that role around the district, she was assigned to Bartram, where she stayed for 17 years.

She made several stabs at college over the years, including at Widener University and at Community College of Philadelphia. But Smith started her journey toward full teacher certification in 2019 — after the youngest of her three children graduated from high school.

At that point, she told herself: “I did my job as a mother. Now it’s time for me to go back and pursue my dream. It was time to do me.”

Schools drawing on paraprofessionals’ experience with kids

Smith eventually earned an associate degree in education from Delaware Community College in 2020.

Although she had worked as a paraprofessional in a high school, she decided she wanted to teach the youngest children. What she learned from being around teenagers, she explained, was that they needed help earlier.

“I wanted to catch them when they were little,” she said, “to give them structure, to help especially with their social-emotional learning.”

She also realized, from her experience as a parent and from her years at Bartram, that the road to reading proficiency has to start early as well.

Two years after she earned her associate degree, the district started Para Pathway, which is run through a partnership between the district and the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers.

“We wanted to draw on the experience of educators who worked in our system to begin with and had experiences with our kids,” said PFT President Arthur Steinberg, explaining some of the motivation for Para Pathway. “They’re invested in the system, and are less likely to leave. And they look like the kids in the community, and a lot of times they know the parents.”

He added that the district now has to ensure that those who’ve transitioned from paraprofessionals to fully certified teachers “get the proper support.”

Catanch-Bradley, the principal at Bethune, added that teachers’ solid middle-class salaries give those like Smith “the ability to be bigger providers for their families,” compared to the $18.35 an hour earned by paraprofessionals.

“We’re excited,” Catanch-Bradley said.

Smith also has flexibility when it comes to future teaching positions: Her certification allows her to teach up to the fourth grade.

While Philadelphia has several early childhood programs, including some that are under federal Head Start, of which Bethune’s program is a part. There is also PHLpreK, which former Mayor Jim Kenney worked hard to expand.

On Tuesday morning, her second day on the job, she was already responding to children’s various needs.

Of her 10 students, three of them had never been to school before. One little boy wailed pitifully and then fell asleep. She let him be. A little girl wandered around and protested loudly if she was unhappy about something. When she screeched, Smith coaxed her onto her lap and calmed her down.

Smith never looked ruffled or nervous. She had help from her very experienced classroom assistant, Anita Parker, who said she has been working in early childhood education since 2002. In fact, Parker might have thoughts about becoming a fully certified teacher herself one day.

“She’s doing great,” Parker said of Smith.

Smith herself is confident, although the dictates of the curriculum — with its focus areas, question of the day, schedule requirements, and specifications for daily large-group and small-group activities — can be daunting.

“Once I get this curriculum down, it’s a piece of cake,” she said. “I love the little ones, and I’m glad I did this.”

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.