Robert C. Williams’ great-grandmother, who raised him, made sure he went to school.

“My story was that I always liked going to school, I had to go to school,” Williams recalled.

But he “got in with the wrong crowd” and started losing interest in his courses because he wondered where they fit into his future.

By his own telling, he was on his way to dropping out of Edison High School in 1980 when he got back on track to graduate and his life path was set by a program that started in the school district just over a decade before: Philadelphia Academies, Inc.

Williams went to the school-within-a-school for applied electrical science, which happened to be the first one established in the city. Williams went on to a decades-long career as an electrician and electrical engineer.

“It was the best thing they could have done for me,” he said.

Philadelphia Academies was founded in the school district in 1969, amid concern that students of color were being shunted disproportionately into non-academic, “vocational” courses. Since then, the organization has walked a fine line between keeping students interested in school and giving them practical skills, while not seeming to limit their horizons. But over the last several years, the organization has refined and expanded its mission to meet changing workforce needs.

As it did when the group started, Philadelphia Academies focuses on preventing students from dropping out. Its 9th Grade Success Network provides support in 24 high schools to concentrate on the needs of students in their freshman year, when the slide toward dropping out often begins. And its programming is still rooted in particular careers and trades.

But now, Philadelphia Academies, which serves about 6,800 students, also stresses the importance of going to college, and clearly defines its role as giving students options while connecting their education to the real world. It’s also evolving away from its self-contained model and towards working in 32 schools through career and technical programs and the ninth grade success network.

“The mission is more now about how to make school a place where students want to attend” through interesting, practical courses, said Christopher Goins, the organization’s president and CEO. “They pick their direction.”

The initiative recently released data showing that in the high schools where Philadelphia Academies has a presence, the percentage of Black and Latino ninth graders on track to graduation is increasing at a greater rate than at high schools where the program is not located.

The group has also branched out into areas that some people might not associate with career-oriented programs. Earlier this month, the organization received a roughly $399,200 state grant to support its career pathway program focused on early childhood education at Parkway West High School.

Also in October, the City Council adopted a resolution from Councilmember Anthony Phillips commending Philadelphia Academies.

Nazirrah Terry, a Parkway West junior who lives in Strawberry Mansion, applied to the high school specifically because of the early childhood program. “I want to work with children,” she said, adding that she has “a bunch” of younger siblings.

Terry aspires to eventually work in, or even own, a day care center.

Program expands its reach, career options for students

Philadelphia Academies — or PAI — was established 55 years ago in response to an alarming dropout rate, especially among Black boys. It did so at the urging of civic leader Charles Bowser and Lee Everett, an executive with PECO, the city energy company, as a strategy to keep students on track to graduation.

For most of their history, the academies operated as schools-within-schools that emphasized practical skills in fields including construction, health care and hospitality. It also formed partnerships with local industries so students could be more connected to the world of work.

Of the 32 career and technical education programs supported by PAI, eight of them are now middle schools. That’s because the organization also wants to plant the seed of career awareness in younger students while also assuring that they enter high school prepared for the more rigorous coursework, especially in math.

“We expanded to middle schools so they don’t come into 9th grade off track,” Goins said.

In the current PAI model, students visit employers and participate in workshops on career development, financial literacy, resume writing, and interviewing.

Over the years, there have been academies focused on banking, law, and aerospace engineering. Programs supported now range from culinary to cybersecurity, construction trades to tourism, health to sports marketing, horticulture to film and video.

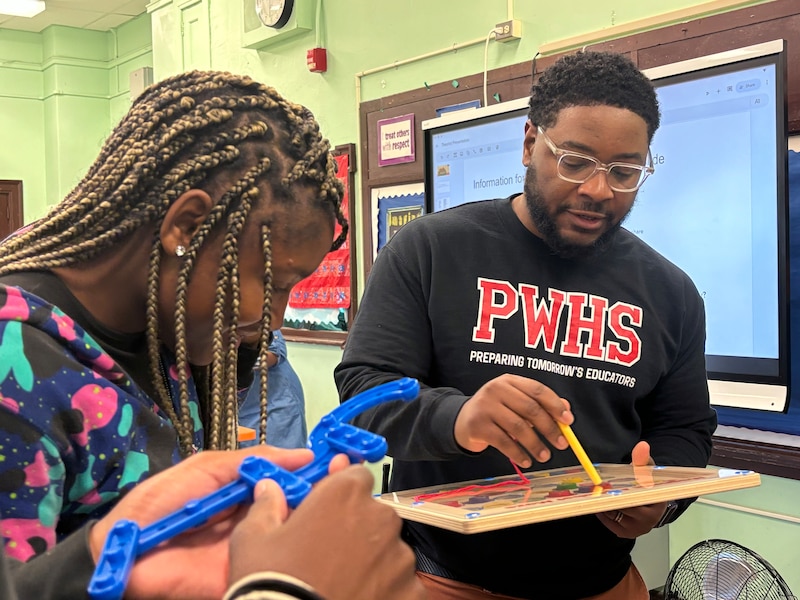

While the program focused on careers in early childhood education might be relatively recent, it does hearken back to the organization’s roots by evolving the focus on Black boys from dropout prevention to establishing “a robust pipeline to support more Black men becoming educators,” Goins said.

Roughy 4% of the teachers in Philadelphia are Black men; the nationwide figure is around 2%.

Parkway West Principal Will Brown said if you had told him when he was age 12 that he would grow up to be a teacher, he would have laughed. But that’s what he became, after he had a high school internship working with young children. Now he heads the 220-student school.

He envisions Parkway West’s early childhood pathway starting to prepare students for teaching at all levels, as well as for other careers that involve working with children and families.

“Not everybody wants to be a teacher, but if they decide to be a counselor or a social worker, we want them to have foundational knowledge of young people,” Brown said.

Kingston Wright, an 11th grader at the school, said he “didn’t know the school had early childhood education until I got here,” he said.

But now, based on his experiences learning about young children, he has decided he wants to go into “some sort of teaching.” Over the summer, he had a six-week internship at a child care center. “I like working with [children],” said Wright, 16. “That influenced me.”

Junior Jay Bush, also 16, said he wants to be a history teacher. “This class helps me understand kids, what they need,” he said.

Data suggests Philadelphia Academies helps students with coursework

Recent data provided to Chalkbeat by PAI indicates that the support offered by the program could be helping students with their overall academic course load.

For the last school year, 68.8% of ninth graders in the district were on track to graduate in schools getting PAI support. That was 2.2 percentage points higher than in those schools for 2022-23, according to the organization’s analysis.

The school district says ninth graders are “on track” if they have earned at least a C in classes in the four core subjects — math, science, English, and social studies — plus one other course. The district says students who are on track at the end of ninth grade are more than twice as likely to graduate.

At 66.7%, the on-track figure for Black boys was 5.7 percentage points higher than the year before, the figure for Black girls was 5.8 percentage points higher at 71.3%.

The overall on-track rate for all district high schools without the academies program is 77.9%. That figure includes selective admissions schools, and it has dipped recently.

Kathryn May, PAI’s assistant director, works with the 9th Grade Success Network. She said that at Jules E. Mastbaum High School, the on-track percentage has gone up by 19.7 percentage points to 69 percent since 2021.

“We’ve seen a lot of practices that have worked at one school adopted by other schools,” May said.

May coaches Amy Foster, Mastbaum’s assistant principal for ninth grade, and studies data to see which students need extra support so “we can put interventions in place,” she said.

Foster said the Philadelphia Academies team helps her work with teachers whose students are chronically failing their classes to see how they can adjust their teaching to help more students pass classes like Algebra 1.

As for Robert C. Williams, he was grateful for his career in the electrical field, but always felt something was missing. He was working at the Marriott Hotel engineering department when he took the day off and caught an episode of “Oprah.” The subject, he said, was “finding your passion.”

“I remembered when my great-grandmother would ask me what I wanted to be, I would always say, ‘a teacher,’” Williams recalled.

So, while still working, he enrolled at Community College of Philadelphia, then Temple University, then Lincoln University. He earned two degrees in education. For years, he went on interviews for teaching jobs, but didn’t get hired.

Eventually, he got a phone call from the Philadelphia district. There was an opening for an electrical teacher at Mastbaum.

He just started his seventh year there.

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org .