Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with news on the city’s public school system.

When Adrienne Staten’s fellow teachers first started talking about using artificial intelligence tools in their classrooms, Staten was not on board.

“AI was scary to me,” said Staten, who’s been a Philadelphia educator for 27 years. “It was like some ‘I, Robot,’ they’re going to take over the world kind of stuff.”

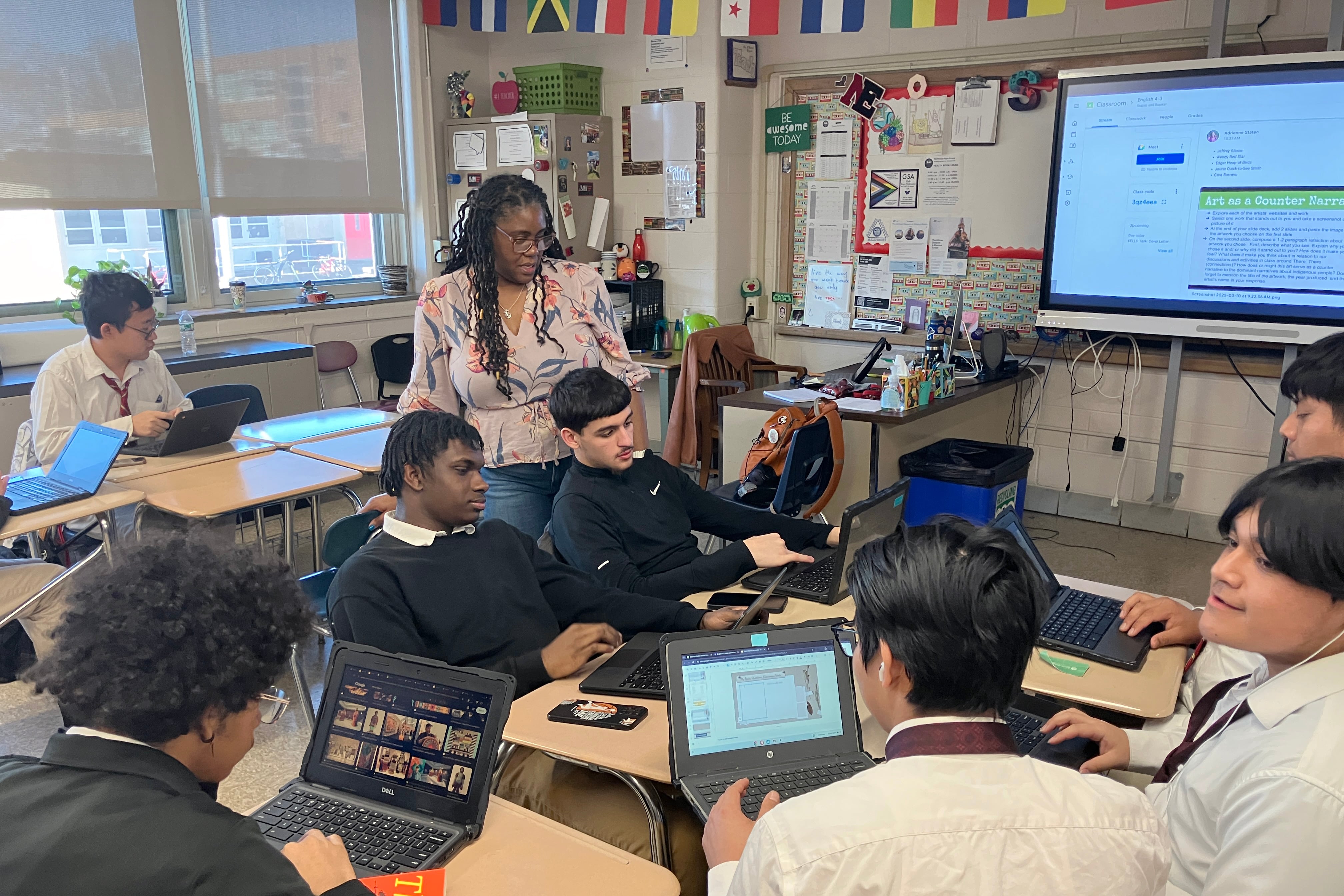

Staten teaches English at Northeast High School, the city’s largest high school, where many of her students have learning disabilities, are dealing with trauma and mental health challenges, or are learning English. She said she didn’t think incorporating a new technology into her lesson plans would help much.

Then, about three years ago, a colleague wrote Staten a poem using an AI chatbot. That completely blew her mind, she said. From there, Staten decided she had to learn more about generative AI, how it works, how she could use it as a teaching tool, and how to inform students about the pitfalls, biases, and privacy dangers of the emerging technology.

AI companies have made grand promises to teachers and school leaders in recent years: Their product will personalize student learning, automate tedious tasks, and in extreme cases, transform the role of teachers altogether. But experts have also raised ethical concerns about how student data is used (and misused) by AI companies, how students can use AI for cheating and plagiarism, the erosion of critical thinking skills, and the spread of misinformation.

Philly school officials say they’re grappling with these questions, while also asserting that the district is leading the way on AI through a professional development program that begins this year. The district has established detailed guidelines and procedures for using AI that attempts to protect student data privacy. But those policies haven’t stopped the district from rethinking certain tasks, like the way teachers design assessments and judge skills such as writing.

As the technology becomes more advanced and embedded within peoples’ lives, teachers like Staten want more support and guidance about it. That means the district must respond and evolve quickly. They also want to guard against how previous technological innovations affected schools and students.

“Everyone seems to have forgotten all of the lessons learned from the social media era,” said Andrew Paul Speese, deputy chief information security officer for the district. “If this tool is free, you are the product.”

How Philadelphia schools are experimenting with AI

When ChatGPT became popular a few years ago, Staten said, “I think we all as teachers were uncomfortable.” Their first thought was that students would use it to cheat, she said.

But what she found is that some of her students were “petrified of it.”

“They don’t understand how it works. They don’t get the idea that just because it spits something out, it doesn’t mean you have to use it,” she said.

Staten can relate. Her early days of teaching involved a lot of printed paper, textbooks, and handwriting. When the district gave teachers “brand-new, shiny computers,” they sat unused in her classroom. She said she was not a particularly tech-savvy person — until COVID.

Now, every student has a Google Chromebook laptop, and the access to technology has transformed how Staten thinks about lesson planning. Being able to do their own research gives all of her students ownership of the lesson, and it’s changed how they respond to activities, Staten said.

Her students who are English learners have found using AI helps them feel more comfortable with their writing and grammar while also giving Staten an opportunity to talk about tone and voice in their writing.

The AI will “spit something out,” and then it’s a conversation starter with that student to determine “is that really you? Does that sound like you? Do you know what this word means?”

Ultimately, Staten said she wants her students to learn how to use machines as a tool to help them locate their humanity within their own writing.

In general, that’s the sort of attitude the Philly school district wants to cultivate. But the district has also prioritized being very clear about what the policies are for acceptable use of AI that guide that enthusiasm, said Fran Newberg, deputy chief in the district’s office of educational technology.

Since November, the district has been training teachers to work with two approved generative AI tools: Google’s Gemini chatbot (which is available for high school students and staff) and Adobe’s Express Firefly image generator (available for all K-12 students).

Both of those programs are examples of generative AI, which includes any tools that draw on a dataset to create new work, such as large language model chatbots like ChatGPT, or programs that produce images, music, or video.

The district’s guidelines for generative AI provide broad resources for some of the most frequently asked questions about academic integrity, verifying information produced by an AI tool, and some examples of how AI could be used in the classroom.

Above all, the district’s guidelines say educators must require students to disclose their use of AI and use citations where applicable.

Balancing passion with appropriate limits can yield encouraging results. At one district school, Newberg said elementary students wrote detailed descriptions of their own imaginary mythological bird creatures. Then, they drew pictures of what they thought their bird would look like. At the end of the project they plugged their descriptions into Firefly.

She said those students looked on in wonder as their drawings and paragraphs were brought to life.

School leaders worry about student data privacy, safety

The district’s approach to AI policy has provided a foundation for what some experts hope will guide national efforts to use AI in education.

Starting this month and next, the district is rolling out a new professional development program called Pioneering AI in School Systems, or PASS. Developed in conjunction with the University of Pennsylvania, PASS provides three tiers of professional development involving AI — one for administrators, one for school leaders, and one for educators.

Michael Golden, vice dean of innovative programs and partnerships at Catalyst @ Penn Graduate School of Education, said by the fall of this year he and his colleagues hope to make PASS available to any school district in the country and across the globe.

“We’re building on the prowess and expertise in Philadelphia to create something that’s scalable and usable in many different contexts,” Golden said.

The district’s enthusiasm for and caution about AI are part of what made Philly an attractive option for the professional development program. But in some ways, the district was pushed to embrace the technology.

Speese, the district’s deputy chief information security officer, said two things happened that forced the district to take AI seriously.

First, in August 2023, an influx of Philadelphia teachers asked for support and information about generative AI just as New York’s school chief made a decision to block ChatGPT citing “negative impacts on student learning, and concerns regarding the safety and accuracy of content.”

Then, Microsoft made its AI assistant, called Copilot, a mandatory part of their software.

Philadelphia has been a Google-centric district. But Speese said he knew if Microsoft was mandating AI in its software, he suspected Google would soon follow. If district officials banned AI tools altogether, it could completely cripple student computers, email servers, and other systems. A blanket ban could also push some students and teachers towards untested models, putting themselves and their schools at risk.

“Obviously, even if we tried to block it, people are going to be using it on their mobile phones so how do we enable you to use these tools in a way that makes sense within our environment?” Speese said.

So district officials set about changing contracts to include language about safe data collection, privacy, and data storage.

The contract language stipulates the data a student feeds into the tools and the output those tools generate must be “housed exclusively in the United States,” can’t be sold or shared without permission, and that vendors won’t use the data to train their AI models.

“Parents have a right to feel that we are doing everything we can to protect their children’s digital footprint,” said Newberg, the deputy chief for education technology.

AI companies have run afoul of other state’s laws and other school district’s rules. One whistleblower told Los Angeles school officials that the AI tool their district adopted was misusing student records and left sensitive student information open to potential hackers.

Newberg drew a connection between AI and the reaction to the rise of social media. She said district leaders initially brushed off social media as a tangential development. But then social media started impacting students’ mental health, increased cyberbullying, and broadcast photos and sensitive student data to the world.

“We want our students to start having agency and start being skeptical,” Newberg said. “We were not as smart with social media.”

But new, free, and experimental AI tools pop up every day. It’s hard for guidelines and rules to keep up.

For teachers like Staten, educating her students about the biases embedded in these systems, how to protect their privacy, how to see through misinformation, and recognize when a fact is actually an AI-generated hallucination, is paramount. And that’s what keeps her up at night.

“I just want to know that I gave them all the equipment and tools that they need to be okay out there,” Staten said. “It’s a process. I realize that it’s going to take some time.”

Carly Sitrin is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Philadelphia. Contact Carly at csitrin@chalkbeat.org.