This story about early math instruction is part of a series about innovative practices in the core subjects in the early grades. It was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

BERWYN, Ill. — In the last decade, educators have focused on boosting literacy skills among low-income kids in the hope that all children will read well by third grade. But the early-grade math skills of these same low-income children have not received equal attention. Researchers say many high-poverty kindergarten classrooms don’t teach enough math and the few lessons on the subject are often too basic. While instruction may challenge kids with no previous exposure to math, it is often not engaging enough for the growing number of kindergarteners with some math skills.

During the last school year, only 40 percent of fourth-graders nationwide scored at a proficient level in a nationwide math assessment. Even more alarming, just 26 percent of Hispanic students and 19 percent of African-American children tested proficient in fourth-grade math. That is significant because strong math skills are needed for some of the fastest growing jobs of the next decade and are requirements for many of the highest paying jobs.

Understanding and being able to work with numbers “is a fundamental skill for success in almost any occupation you might choose,” said economist Greg J. Duncan of the University of California Irvine’s School of Education, whose research examines child poverty and education. “It leads to the analytic, higher-level thinking that’s increasingly important.”

One district that is steadily ratcheting up its achievement levels, with a focus this year on mathematics, is located in a small Chicago suburb. Two years ago, just 14 percent of third-graders in Berwyn North School District 98 — a high-poverty, mostly Hispanic school district about 30 minutes from downtown Chicago — were able to do grade-level math. That was the district’s first year taking the PARCC assessment, a college- and career-readiness test mandated by the state of Illinois, and the results were dismal, though not exactly surprising.

“When we started here in 2012, our district was the lowest performing in math and reading of all the schools that feed into Morton West High School,” said Carmen Ayala, Berwyn North School District 98’s superintendent.

Ayala, the district’s first woman and first Latina in the top spot, rolled up her sleeves. “Turning this around isn’t something you can do during a couple of workshops,” said Ayala. “For us, the focus had to be on equity because our district is 96 percent children of color, but 90 percent of our teaching staff is white. It’s not just about teachers teaching. It’s how we recruit, how we use resources, how we conduct business in the district.”

Although Illinois adopted Common Core standards in 2010, Berwyn North, a kindergarten through eighth-grade district with 3,084 students, had not yet incorporated the standards when Ayala and her new assistant superintendent, Amy Zaher, were hired in 2012. “When I started, the consistent word was how inconsistent we were,” said Ayala.

Ayala and Zaher created a set of goals for fixing Berwyn North that included an entirely new, district-wide Common Core standards-based curriculum that aligned through each grade, fixing the district’s special education inclusion program, upgrading programs for English learners and better integrating technology into schools and classrooms.

These goals still guide the district today. “We’ve become laser-focused on these areas in order to really bring up the achievement levels,” said Ayala.

Related: Eight ways to introduce kids to STEM at an early age

In a district where almost 30 percent of the students are learning English, these goals have meant a radical change in how math is taught in the early grades. Ayala said that before she took over, math lessons were basically one-size-fits-all, making it especially difficult for kids learning English to absorb what was being taught.

“We needed to change how we’re teaching math, especially for our English-learners, so that we were paying attention to language development and communication skills — how our teachers are helping our students express themselves and connect their experiences with what they were learning,” said Ayala.

This connected closely to the common core mandate that children learn to discuss their thinking about math problems, and to approach problem-solving in a variety of ways, rather than simply producing the correct answer. One way the district is applying this standard is via “number talks,” a math practice that encourages students to discuss and critique math solutions, helping kids develop into flexible and creative mathematical thinkers.

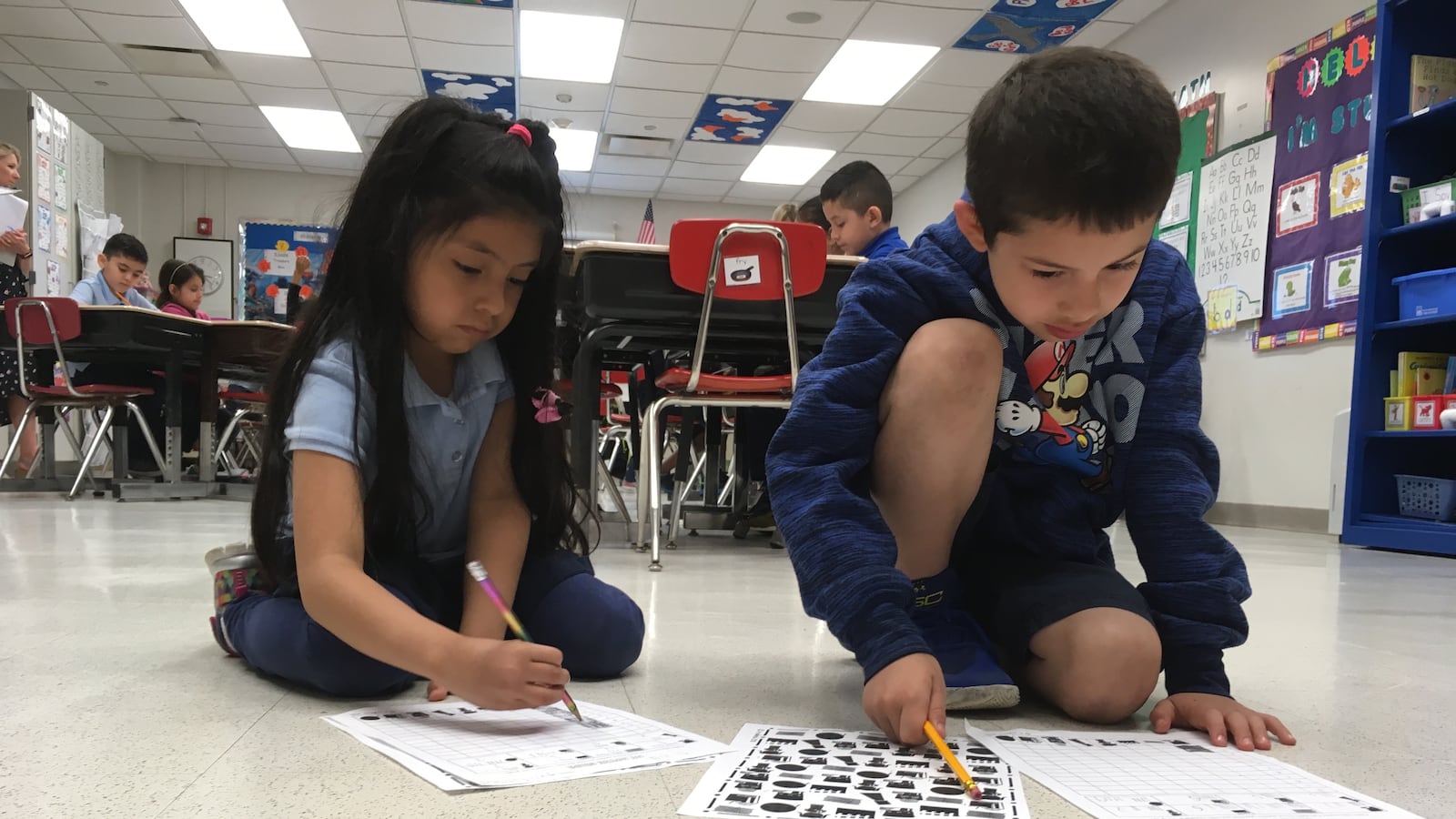

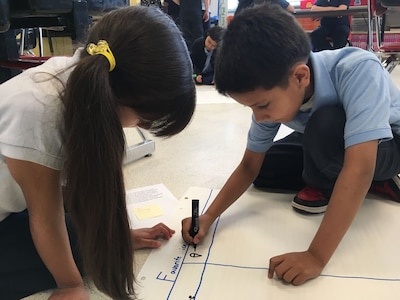

On a recent spring day, Maritza Cleary’s third-grade class at the district’s Prairie Oak Elementary School tackled math pictographs. Children sat together in small groups at tables and on the floor with large sheets of paper and markers spread out between them. Cleary was not the only adult in the room: Four adults — teachers and administrators from the district there to observe Prairie Oak teachers at work — meandered between the groups, scrawling notes onto clipboards, sometimes kneeling beside the children to listen as they worked out the problem.

A pictograph query, a way of showing information using images, was projected onto a whiteboard at the front of the class:

“Mrs. Cleary is having a last-day-of-school ice cream party for her third grade class. She did a survey to find out what flavor each student preferred. There were 10 votes for chocolate, eight votes for vanilla, four votes for strawberry, and three votes for coconut. Use the information from the survey to create a pictograph that shows the preferred ice cream flavors. Create an ice cream symbol for your pictograph that represents two students.”

Students quietly discussed possible solutions, and sketched out ideas on small dry-erase boards before drawing their solutions on the poster-size sheets of paper. Cleary pulled a chair close to a group, listening intently as her students debated the ideal ice cream cone data layout strategy — an opportunity to flex their math skills and, in the process, become stronger communicators and mathematicians.

Shortly after this classroom visit, 30 teachers and administrators who had spent the day visiting the school’s classrooms — including the four adults who observed Cleary’s class — sipped coffee and nibbled pastries in a windowless conference room in the basement of the school. It was the second and final instructional round of the school year at Prairie Oak (the first was last fall). Instructional rounds, modeled after medical rounds, are an opportunity for educators to observe classroom instruction, and then address problems together in an effort to improve their teaching. This year, the district’s instructional rounds focused on the quality and depth of math instruction.

At this Prairie Oak session, educators looked for improvements on math-related issues identified last fall during the school’s first instructional round. Were teachers working more closely with instructional coaches? Were lessons rigorous enough? Was classroom management stronger? Were students willing to take risks? In a post-rounds wrap-up session, teachers and administrators discussed positive growth, including greater student participation and more productive math talks between students. The group also noted areas requiring improvement: Teachers needed to use classroom wall space to better promote mathematical thinking, for example, and they needed to step back more frequently to allow students to work out their own creative solutions.

Instructional rounds, first brought to the district by Assistant Superintendent Zaher, who learned the practice at her previous job as a Chicago Public Schools administrator, are clearly an effort to unite a formerly disjointed, low-achieving school district around a common vision — 100 percent of students meeting high academic standards — and, importantly, to adopt a cohesive curriculum, connected grade-to-grade and school-to-school.

Related: Why very young children can — and should — learn math

That push for a common, connected curriculum also includes what happens before, and during, kindergarten. Until recently, researchers believed that instilling strong foundational math skills before children enter kindergarten was the best predictor of success in school and life. For those children who missed out on a quality preschool experience, especially poor children of color, catching up in the elementary years was considered unlikely.

Today, this thinking is evolving, putting into question just how permanent the advantage may be for children who benefit from rich math curriculums in high-quality preschools. The reason: The early-math boost tends to fade out once children enter elementary school classrooms where teachers often focus on helping students who did not benefit from preschool prep, neglecting to teach more advanced skills to the advanced learners.

Last year, 43 states, plus Washington, D.C. and Guam, poured $7.6 billion into publicly funded preschool. In the past few years, researchers have begun exploring how to take advantage of that powerful preschool bump, especially in math, while also ensuring students who didn’t go to preschool could catch up. One of the biggest roadblocks, experts say, is the disconnect between preschool and elementary school math curriculums.

UC Irvine’s Duncan, co-author of a seminal study linking early math and reading skills with later academic success, noted that recent research using strong math curriculums in preschool or Head Start programs showed it is possible to level the math-skills playing field among low-income and middle-class children in the early grades.

The weak spot occurs once kids enter elementary school and kindergarten teachers become absorbed with teaching students who don’t yet know their numbers.

“There’s really not much point [to high-quality preschool] if we don’t work on this task of aligning kindergarten and first-grade classrooms — setting them up to take advantage of the skills built up in the preschool year,” said Duncan. “If most children benefit from preschool or Head Start before heading to [a] kindergarten where teachers are skilled, and coached and supported to build on those gains, then you’ve got a situation for low-income kids that’s on par with middle- or upper-middle-class kids who come into kindergarten knowing their letters and numbers and teachers just take off from there.”

Another neglected area contributing to the national math achievement gap, is the lack of math emphasis at home. “Parents focus on reading to their child much more than they do on math skills. We’ve not been very successful so far in convincing parents — as we have with reading — to ‘count with your child’, ” noted Deborah Stipek of the Stanford Graduate School of Education.

In Berwyn North District 98, math scores are steadily creeping upward. Last year, 33 percent of Hispanic third-graders met or exceeded math grade-level expectations on the PARCC test — nearly double the percentage from 2015. Berwyn North recently turned another stat on its head: Of the four districts that feed into the local high school, Berwyn went from dead-last to leading the pack in both math and reading achievement.