The parent, wearing an “I Love NTA” T-shirt, said it loudly and directly toward the end of the public comment section Thursday night. “It sickens me to be here today and see so many people fighting for scraps,” said Kawana Hebron, in a public meeting on the boundaries for a proposed South Loop high school on the current site of National Teachers Academy. “Every community on this map is fighting for scraps.”

The 1,200-student high school, slated to open for the 2019-2020 school year near the corner of Cermak Road and State Street, has become a wedge issue dividing communities and races on the Near South Side.

Supporters of NTA, which is a 82 percent black elementary school, say pressure from wealthy white and Chinese families is leading the district to shutter its exceptional 1-plus rated program. A lawsuit filed in Circuit Court of Cook County in June by parents and supporters contends the decision violates the Illinois Civil Rights Code.

But residents of Chinatown and the condo-and-crane laden South Loop have lobbied for an open-enrollment high school for years and that the district is running out of places to put one.

“I worry for my younger brother,” said a 15-year-old who lives between Chinatown and Bridgeport and travels north to go to the highly selective Jones College Prep. She said that too many students compete for too few seats in the nail-biting process to get into a selective enrollment high school. Plus, she worries about the safety, and environment, of the schools near her home. “We want something close, but good.”

One by one, residents of Chinatown or nearby spoke in favor of the high school at the meeting in Hermann Hall at the Illinois Institute of Technology. They described their long drives, their fearfulness of dropping off children in schools with few, if any, Chinese students, and their concerns about truancy and poor academics at some neighboring open-enrollment high schools.

But their comments were sandwiched by dissenting views. A member of South Loop Elementary’s Local School Council argued that Chicago Public Schools has not established a clear process when it comes to shuttering an elementary and spending $10 million to replace it with a high school. “CPS scheduled this meeting at the same time as a capital budget meeting,” she complained.

She was followed by another South Loop parent who expressed concerns about potential overcrowding, the limited $10 million budget for the conversion, and the genesis of the project. “It’s a terrible way to start a new high school – on the ashes of a good elementary school,” the parent said.

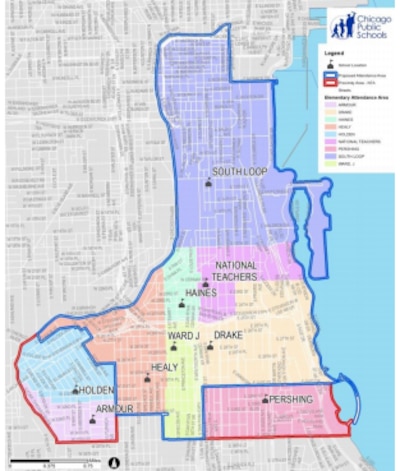

The most persistent critique Thursday night was not about the decision to close NTA, but, rather, of the boundary line that would determine who gets guaranteed access and who doesn’t. The GAP, a diverse middle-class neighborhood bordered by 31st on the north, 35th on the South, King Drive to the east and LaSalle Street to the west, sits just outside the proposed boundary. A parade of GAP residents said they’ve been waiting for decades for a good option for their children but have been locked out in this iteration of the map. Children who live in the GAP would have “preference” status but would not be guaranteed access to seats.

“By not including our children into the guaranteed access high school boundaries – they are being excluded from high-quality options,” said Claudia Silva-Hernandez, the mother of two children, ages 5 and 7. “Our children deserve the peace of mind of a guaranteed-access option just like the children of South Loop, Chinatown, and Bridgeport.”

Leonard E. McGee, the president of the GAP Community Organization, said that tens of millions in tax-increment financing dollars – that is, money that the city collects on top of property tax revenues that is intended for economic development in places that need it most – originated from the neighborhood in the 1980s and went to help fund the construction of NTA. But not many of the area’s students got seats there.

Asked how he felt about the high school pitting community groups against each other, he paused. “If we’re all fighting for scraps, it must be a good scrap we’re fighting for.”

The meeting was run by Herald “Chip” Johnson, chief officer of CPS’ Office of Family and Community Engagement. He said that detailed notes from the meeting will be handed over to the office of CEO Janice Jackson. She will make a final recommendation to the Board of Education, which will put the plan up for a vote.