For Chicago students, learning how to write will soon get more complicated.

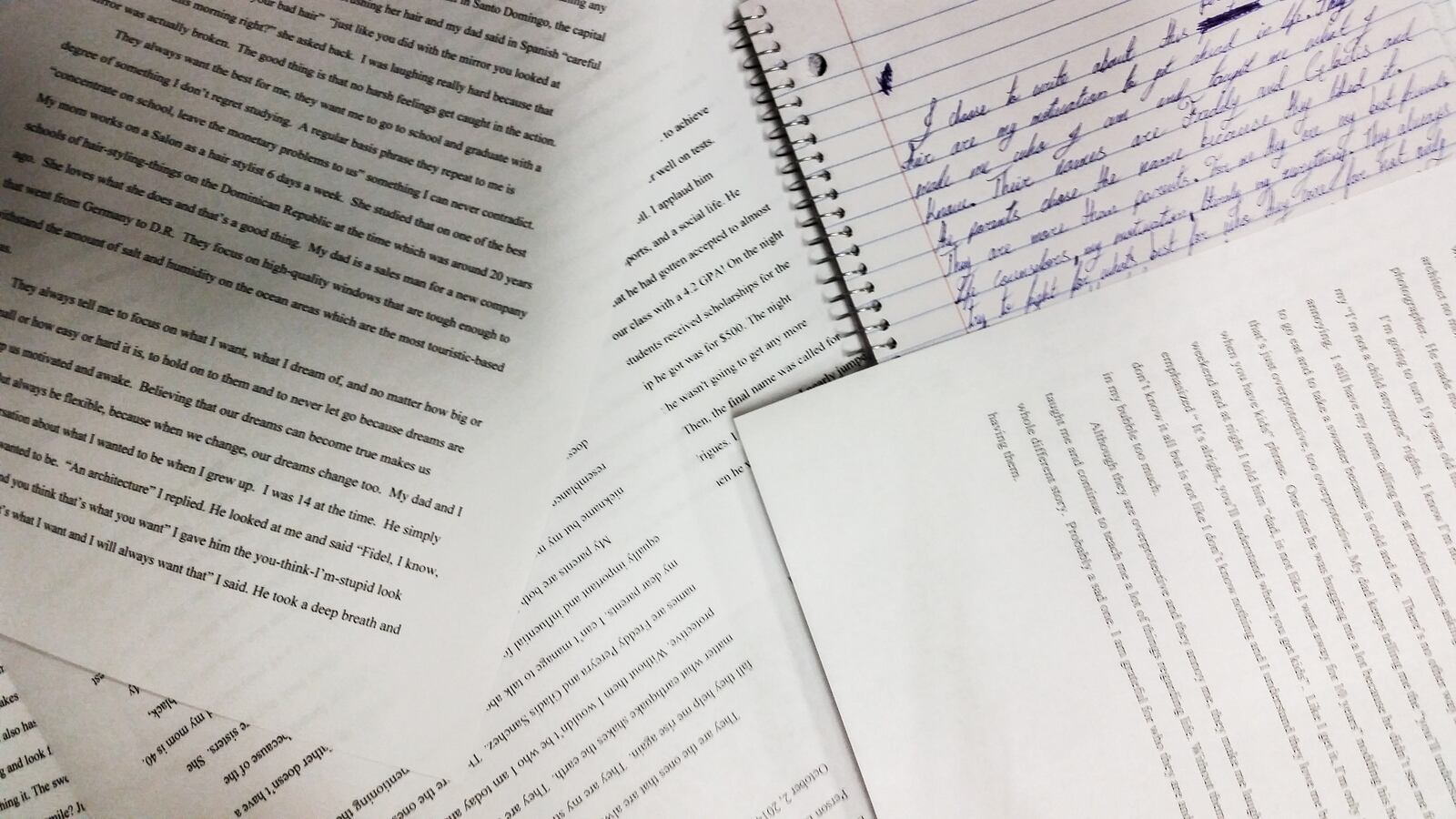

Starting this school year, Chicago Public Schools students will have to learn cursive writing before the end of fifth grade.

What was once a skill taught to children across the nation, cursive was elective in states like Illinois in the past several years under cursive-less Common Core State Standards. But at a meeting Wednesday, the Chicago Board of Education is poised to adopt a new state-mandated requirement to teach cursive, after making major decisions about revising the student code of conduct and approving a $7 billion budget.

The requirement could burden teachers whose school year already is jam-packed with teaching various requirements and preparing students for annual tests. Cursive will be taught either in grade four or five this school year, and then in only grade four in the following years.

CPS Press Secretary Emily Bolton said that schools will have to teach a minimum five-week unit in cursive writing. The district is developing a sample unit that schools can replicate, she said, or schools may design their own curriculum. The district’s Department of Literacy is also developing a tracking system to monitor implementation of the unit.

Illinois legislators mandated cursive in November, after Governor Bruce Rauner vetoed a bill with the requirement and the Illinois House and Senate both overrode his veto. House Assistant Majority Leader Kimberly Lightford drove the initiative, arguing that cursive writing is essential for students to “write a check, sign legal documents or even read our Constitution.” Before then, Illinois had never mandated cursive and had left it up to local districts to decide if they wanted to teach it. CPS had not required it in recent years.

Policymakers in other states have cited the benefits of cursive on students’ learning outcomes. Karin James is an associate professor at Indiana University who has conducted research that found that learning to write cursive does not impact the speed at which students learn to read cursive. She said other research on the effects of learning cursive is “inconclusive,” and that while studies have shown that writing by hand (whether in print or in cursive) improves students’ ability to retain information, “we need more research done about whether learning cursive specifically is beneficial.”

Some teachers are embracing the new requirement. Tenesha Rawls, who teaches fourth- and fifth-grade special education at Frank Bennett Elementary School in Roseland, already teaches cursive to her students in their free time.

“Legal documents require us to sign in cursive,” she said. “If our students can’t write cursive, they can’t function as individuals in society.”

Others are more hesitant. Christine Dussault is the dual-language coordinator at Chase Elementary School in Logan Square. She said that she was skeptical last year but now is more accepting, depending on how much flexibility teachers will have in teaching cursive.

“Can we be teaching cursive while analyzing primary-source documents, or while also teaching general writing?” she said. “We have so much to cover and only so much time. If they insist on a curriculum without engaging in teacher input, it’ll be hard.”

While having little flexibility would be burdensome, at the same time, teachers also don’t want to be left without sufficient guidance.

Tiffany Harper teaches the fifth-grade gifted program at Beasley Academic Center in Washington Park. She also already teaches cursive to her students during their independent study periods, but only because, she said, her school has provided her time and space to do so.

“Given that the majority of schools on the South Side lack resources,” she said, “if the district is not giving the resources and accurate training that aligns with these mandates then it becomes a huge burden.”

If the district does not provide a guiding curriculum, teachers would have to develop their own curriculum “on top of teaching to the test and teaching students what they need to know,” she said.

“It adds something else to the plate when the plate is already full.”