There’s no debating that childhood trauma seriously impacts how students learn. Researchers have tied stressful events such as divorces, deportations, neglect, sexual abuse and gun violence to behavioral problems, lower math and reading scores, and poor health. The latest research, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, finds that children who endure severe stress are more likely to suffer heart attacks and mental health disorders.

So, we know trauma affects kids, but how do we teach educators to confront it? That’s where Dr. Colleen Cicchetti comes in.

A child psychologist at Lurie Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor at Northwestern University’s medical school, she helps lead the hospital’s efforts to improve how local schools handle trauma. The goal: to train teachers to spot and respond to warning signs in kids. Last Tuesday and Wednesday, about 150 aspiring teachers with Golden Apple’s scholars program attended day-long training sessions.

It’s not the job of a teacher to become a mental health provider, said Cicchetti, who earlier this year was named Public Educator of the Year by the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “It’s really their job to try to understand what barriers are making it hard for them to do their job.”

Chalkbeat Chicago interviewed Cicchetti about training teachers, the cost of childhood trauma in Chicago communities, how it takes a toll on classrooms, and what teachers can do to promote healing in schools.

What are some examples of the different types of trauma Chicago children might be dealing with?

Seeing someone shot, seeing someone stabbed. It could be sexual abuse, it could be physical abuse. It could be parents incarcerated, divorced, separation, death. It can be someone that you know being killed, someone you know in a car accident.

What are some ways that trauma finds its way into the classroom?

Flashbacks, difficult sleeping, difficulty eating, choosing not to — or being unable to — enjoy the things you used to enjoy. Being hyperalert where you are scanning the space because you don’t feel safe, which impacts your learning. There’s that hopelessness and sense that the world is dangerous. They might be getting in fights. Another thing we sometimes see is frequent absences.

We see some kids who are spending a lot of time in the nurse’s offices, complaining of stomachaches and headaches — their biology is triggered.

We often see it manifest in difficulty negotiating relationships with other people. Some days they can be really engaged with the teacher, the next day they’re really angry and throwing temper tantrums.

How do you teach teachers to recognize trauma?

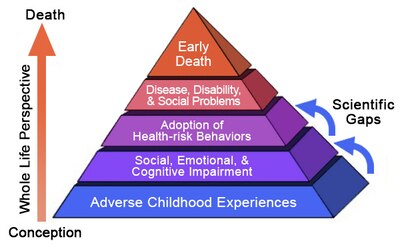

We do these trainings called Trauma 101. We show them pictures of brains and which areas of the brain are impacted by that flight-or-fight response being triggered all the time. We talk about the ACES studies. (Many studies on Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACES, have linked childhood trauma with the development of diseases like diabetes and heart disease, behavioral problems, substance-abuse disorders in adults, and self-harm. But chronic trauma also can disrupt brain development, impair learning, and make it hard to cope with emotions.)

We look at the symptoms you would see [of PTSD] and what that would look like in a classroom. For example, a kid having flashbacks: You might see a kid who is distracted or looking out the window, or they’re having nightmares so they’re coming into class and putting their head on their desks and they’re sleeping during class because the classroom feels safe and they can’t sleep at night. We sort of try to walk between the clinical symptoms and the manifestations you may see in the classroom.

How do you teach teachers what to do once they see signs of trauma? What are they supposed to do?

The first level is to be aware of kids you think are likely to be experiencing trauma in your classroom. What do you do to create a sense of safety, and do that self-regulation and peer building in your classroom? But if you have kids who are sort of experiencing more challenges and those things aren’t working, in Chicago Public Schools we have something called a request for assistance. Teachers can fill out a form and submit it to their social worker or their behavioral health team. Somebody in the school will do a more in-depth assessment or screening. Those kids are then linked to services, either provided by the school or, in some cases, there’s community providers.

There are few — if any — jobs harder than teaching. What are the limits to what teachers can really do?

In a lot of schools, it’s not very safe for a teacher to say ‘I’m struggling with this student.’ But when teachers feel very isolated, and then feel bad and get angry at themselves and at the student, that’s where burnout comes in. What we’re trying to create is a culture within a school, not just the teachers, but from the administration to all the adults in the buildings, that says it’s our job to take care of the whole child here. If a child is struggling, it’s not a bad teacher, it’s a situation we need to modify.

We try to only go into schools and have these conversations when we’re invited in at the systems level, where the administrators are talking about understanding professional development and reflective learning practices for new teachers, and mentoring, so they can understand why this work is crossing over into their home lives, why they’re coming home grumpy, or overeating or drinking, and don’t want to go back to work. It’s hard, but we can teach you what you can do to set your classroom up to be successful, and also make sure you have the right kind of supports, so if you’re seeing a kid who’s struggling — and you’re struggling — that you can reach out to other adults in the building.

What does a safe classroom look like in practice for a kid who has experienced trauma, maybe multiple forms of trauma in their lives?

It’s predictable. [Students] know what expectations are, what they need to do to be successful. There’re different parts of the day where it may be getting hard for them to focus, but then they get breaks.

If you didn’t get your homework done it’s not super punitive. We want to hold people accountable and help them be successful, but let’s say maybe they took three buses to get to school and they were babysitting their siblings last night, so they don’t have enough time for an assignment. Are you going to get a zero or will you be coming in during your recess or lunch break to get this done?

It’s an environment that says, I believe you can be successful, and I’m going to stack the deck for your success. I’m going to provide both physical safety and emotional safety. We’re going to have rules around respecting differences and how we talk to one another. We’re going to have restorative conversations and practices around discipline, so we can not be so reactive. And we’re going to foster relationships both with kids and between each other.