More than four in 10 Chicago teachers feel unsafe at school, a markedly greater percentage than teachers nationally — but at the same time, Chicago teachers also feel better prepared to deal with violence and oppose arming teachers — more so than do their peers across the nation, a newly released survey shows.

These are some of the findings in the first nationwide survey commissioned by the teacher-advocacy organization Educators for Excellence (E4E) that was released on Wednesday. Educators for Excellence, a group of over 30,000 teachers nationwide, partnered with Gotham Research Group to develop the survey questions, and Gotham administered the survey online. They queried 1,000 teachers across the country plus an additional 100 teachers in Chicago.

Jeffrey Levine, president of Gotham, said that the teachers surveyed in Chicago reflected the geographic distribution of teachers in the city and reflected the city’s ratio of charter to district teachers.

These are some of the main findings:

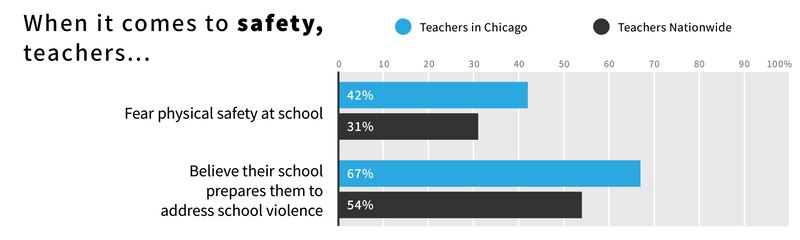

While 31 percent of teachers nationwide fear for their safety in school, the proportion was 42 percent in Chicago. At the same time 67 percent of Chicago educators said they feel their school has prepared them to address school violence, surpassing 54 percent of teachers nationwide. The top three ways teachers nationwide say they may feel unsafe are gun violence, in-person bullying, and fighting among students.

Stacy Moore, the interim executive director of E4E-Chicago, said that this pair of findings “was actually not all that surprising.” She said that because many Chicago teachers feel unsafe, they have also have pushed their schools and the district to provide more training on how trauma affects students and on how to address school violence. Moore noted that in past years, several Chicago schools received federal Healing Trauma Together grants that helped them provide specialized care for students impacted by violence.

“The idea that educators would feel more prepared is the result of the fact that they are seeking those resources,” Moore said.

Math teacher Drew Heiserman said that at his former school, TEAM Englewood, “many students were coming to us with trauma from home and the neighborhood.” In one of the last years he taught at TEAM, “there was a string of seven or eight weeks in row where one staff member was reporting being assaulted by a student.”

He agreed with the findings that Chicago teachers may be more prepared to address violence. He said that teacher training programs in Chicago, such as the one at the University of Illinois Chicago which he graduated from, “gives you a heads up” for what to expect when teaching in the city.

Heiserman also proactively sought resources to address violence when he taught at TEAM. He and his colleagues used resources from Umoja, a Chicago-based organization that develops restorative justice curricula, to implement practices that attempt to resolve conflict rather than punish students for acting up.

Those practices appeared to be effective in changing students’ perspectives, Heiserman said. He found that afterward, many students “didn’t see us as someone to vent to. …They would see us as human beings again.”

***

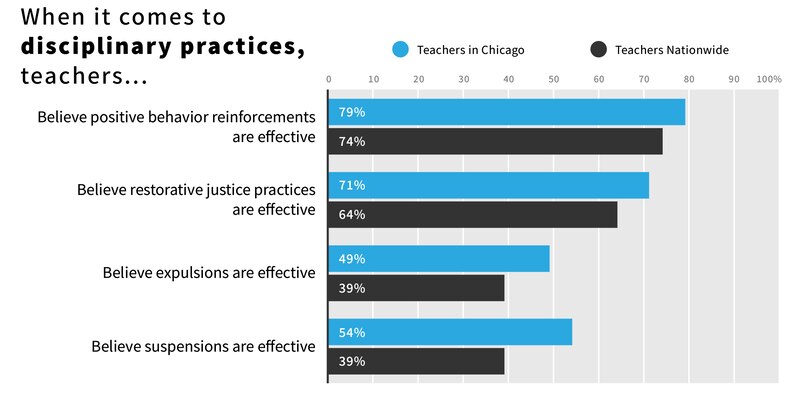

A larger percentage of Chicago teachers believe in restorative ways of addressing discipline than teachers nationwide. For example, 71 percent of Chicago teachers compared with 64 percent of teachers nationwide believe that restorative practices (requiring perpetrators to address the harm caused by their actions) are effective at improving student behavior.

Still, 49 percent of Chicago teachers believe in the effectiveness of expulsions and 54 percent support suspensions. Both surpass the 39 percent of teachers nationally who support each of those two punitive measures.

Writing teacher Melissa Hughes from Michele Clark Magnet High School in Austin offered an explanation for those seemingly conflicting findings. She said considering that Chicago might have more instances of school violence than other cities, then “in areas [in Chicago] where trauma-informed professional development is lacking, it’s very challenging and hard for teachers to know how to address discipline.”

Still, she said that many teachers in Chicago “see that punishments are actually not effective.”

“Teachers are in it because we love our students, and we want to do what’s best for our students,” she said.

She brought up an instance in a “peace circle” — a mediating session — in which two students who had previously fought came up with a code word that indicated when their play-fighting escalated too far into real fighting. The code word allowed them be more cognizant of their own physical behavior in future encounters.

***

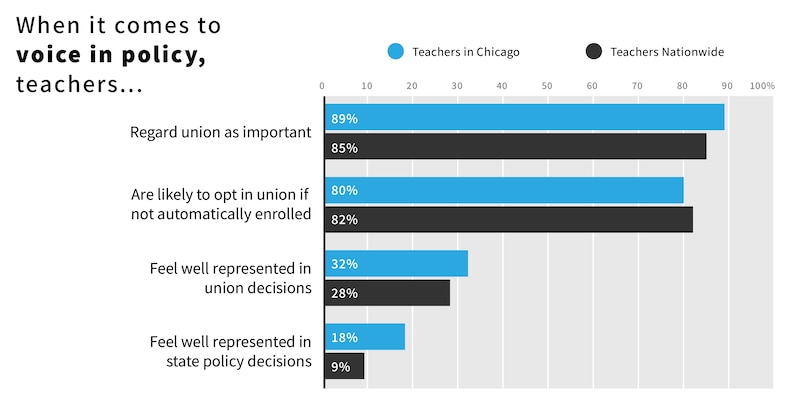

Chicago teachers and teachers nationwide overwhelmingly believe in their unions, 89 percent and 85 percent respectively, and would opt in their union if not automatically enrolled, 80 percent and 82 percent respectively. But only 32 percent in Chicago and 28 percent nationally feel well represented by their unions.

Moore said that this finding is especially important to consider in light of the Janus Supreme Court case in late June, which ruled that members can choose whether or not they pay union dues. “It’s more important than ever that unions are being democratic and listening to all the perspectives of their members,” she said.

But only 18 percent in Chicago feel greatly represented at the state level. The report states that nationwide, “the further teachers are from the decision-making body, the less represented they feel.” This is also true of Chicago teachers.

Kallie Jones, a first-grade teacher at McDowell Elementary School in Calumet Heights and one of the teachers who helped draft the survey questions, said that policymakers need to start with “actually going out and talking to teachers. They need to ask what we want, not guess what we want.”

Moore said that policymakers also should let teachers draft legislation on education policy. For example, she added, E4E-Chicago teachers helped draft two state resolutions that passed this year: HR0795, which urges the state to prioritize school climate and culture and HJR0115, which urges the U.S. Department of Education to sustain an equitable school discipline guidance.

“That was incredibly impactful,” she said. “Teachers continue to want the opportunity to be heard beyond their classroom.”

***

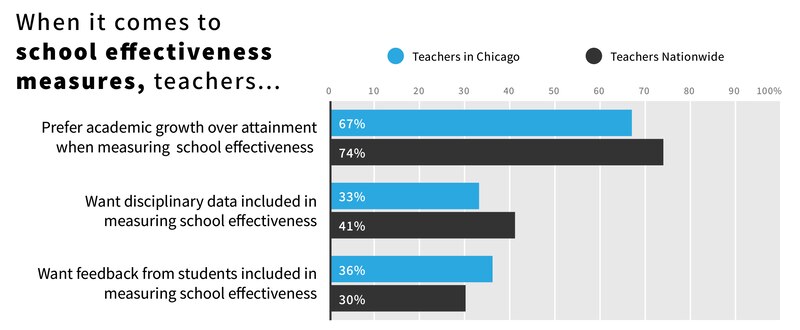

On ways to measure school effectiveness, 67 percent of Chicago teachers prefer using academic growth, compared with 74 percent of teachers nationwide. Both locally and nationally, teachers also want school culture and climate, such as disciplinary data and feedback from students, included in measures of school effectiveness.

Moore said that using growth and non-academic measures of school culture and climate “is something we’re seeing our state take major steps towards.”

Moore noted that in Illinois’ Every Student Succeeds Acts plan, academic indicators make up 75 percent of a school’s rating. Half of the academic measure for elementary schools is based on academic growth. The remaining 25 percent of the a school’s rating is focused on non-academic indicators, which include a measure of school climate and culture.

***

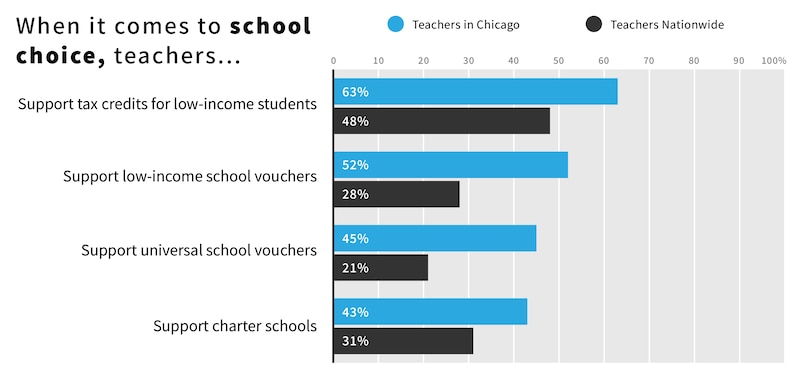

40 percent of Chicago teachers support school choice in the form of universal school vouchers, compared with 21 percent of teachers nationwide. But Chicago teachers condition their support on charter schools being equally accessible and not shifting funds away from district schools.

Read more about the national findings here and the summary of Chicago findings here. Detailed findings about opinons on unions from Chicago teachers are here and from teachers nationwide are here.

Editor’s note: This article was updated to reflect the fact that the percentage of teachers nationwide who would opt into unions if not automatically enrolled, according to survey results, is 82 percent, not 60 percent.