What happens when Mayor Rahm Emanuel headlines a pep rally in a sweltering, Northwest Side high-school gymnasium to promote a $12 million investment in vocational education?

Lots of HVAC jokes, for one thing. And some students fanning themselves with the signs they’d been given that read “Thank you” and “Mr. Mayor.”

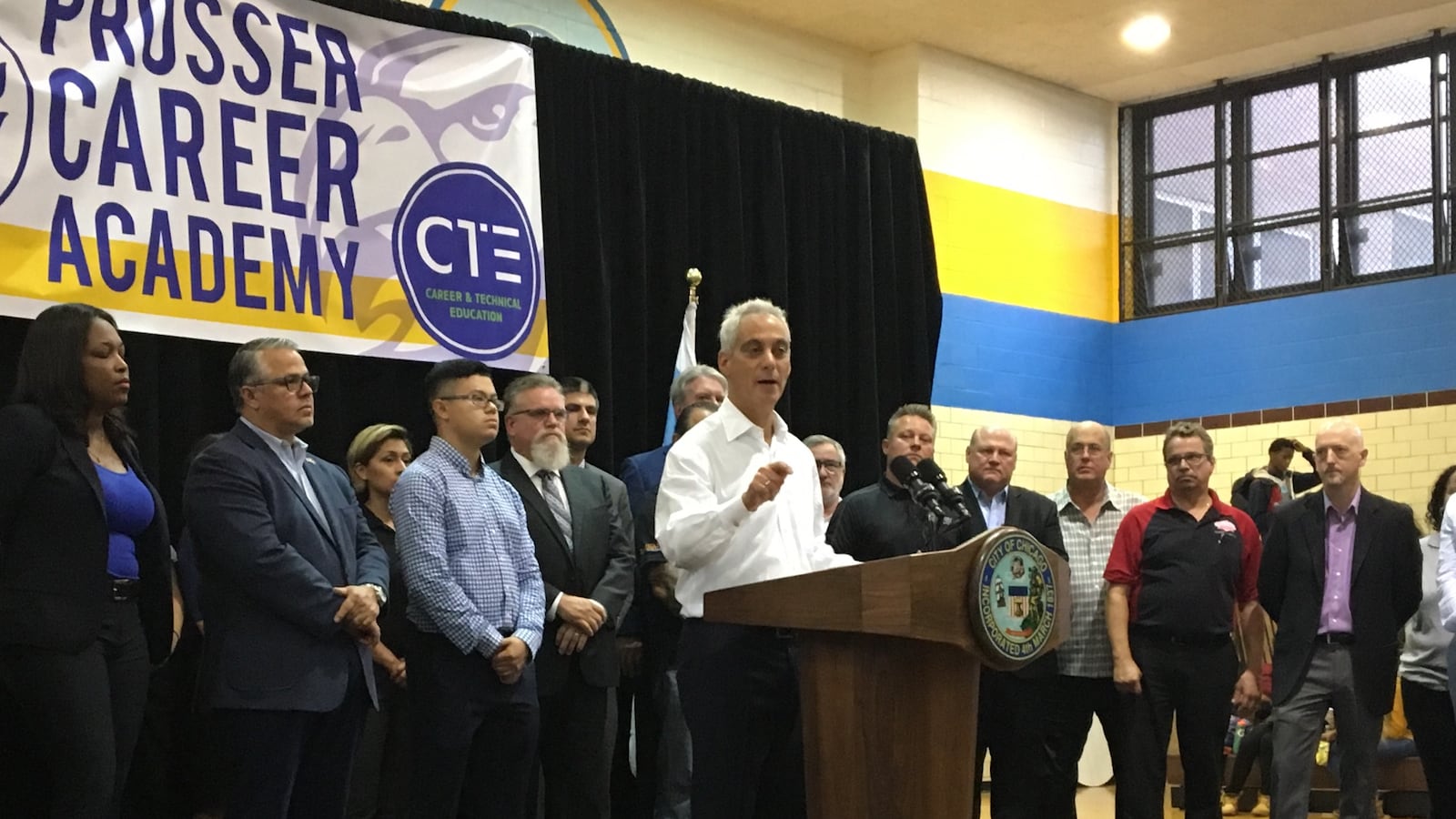

As he makes rounds in the city touting his accomplishments — after announcing Tuesday that he would not run for reelection in February — Emanuel was flanked Thursday morning by luminaries from Chicago Public Schools, area trade unions and employers such as ComEd. On Wednesday, he dropped in on a pre-kindergarten class to push his early-education initiative.

Thursday, there was also lots of enthusiasm about the city’s push to develop career and technical education curricula, to bolster economic opportunity in the neighborhoods.

Part of a $1 billion capital plan announced over the summer, the $12 million investment at Charles A. Prosser Career Academy will expand the school’s vocational training beyond its current emphasis on the hospitality industry to include construction trades including carpentry, electricity and, of course, HVAC.

Many welcome such initiatives as a long time coming. Vocational preparation has been deemphasized in favor of college-preparatory programs, said Charles LoVerde, a trustee of a training center run by the Laborers’ International Union of North America. He’s glad to see the investment.

The city’s current construction trades program launched in 2016 at Dunbar Career Academy High in predominantly black Bronzeville. Prosser makes access easier for West Side students, including the predominantly Latino residents of Belmont Cragin, where it is located.

“Dunbar is a great program, but my kids are not going to go to Dunbar because it’s just too far — it would take them two hours to get there,” said 36th Ward Alderman Gilbert Villegas, who pushed Emanuel to launch Prosser’s CTE program.

Access is important because CTE offerings are among the district’s most in-demand programs, according to a report released last month by the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Demand is not even across demographics, however, with vocational programs more popular among low-performing students, students from economically isolated elementary schools, and black students, according to the report.

Almost one in five seats at district high schools focus on vocational education. But Dunbar’s — and now Prosser’s — focus on the construction trades has Emanuel and Villegas excited, because Chicago’s construction boom means that jobs are readily available.

“There’s not a building trade in Chicago — a carpenter, an electrician, a bricklayer, a painter, an operating engineer — that has anybody left on the bench,” Emanuel told the crowd at Prosser.

Villegas sketched out an idealized, full-career path for a graduate of the new program — one that includes buying a home and raising a family in Belmont Cragin. “I see it as a pipeline that would extend our ability to maintain the Northwest Side as middle class,” Villegas said.

The investment in Prosser comes as part of a broader, national effort to invest in career-technical education. In July, Congress overwhelmingly reauthorized a national $1.1 billion program for job training and related programs.

The new program at Prosser not only will give more students access to training in the building trades, but also will provide proximity to some labor partners. The Laborers’ International Union of North America operates a training center less than a mile from Prosser, where students will have a chance to learn and also visit job sites, LoVerde said.

He said that college-track programs also have their place, but career education presents a clear path to a steady income.

“This gives [unions] a focused path to recruit and find students who are looking for a different path,” LoVerde said. “Becoming a career construction laborer is a job for life.”