This story is part of a partnership between Chalkbeat and the nonprofit investigative news organization ProPublica. Using federal data from Miseducation, an interactive database built by ProPublica, we are publishing a series of stories exploring inequities in education at the local level.

It’s a Thursday morning at Roosevelt High School, and Gillian McLennan’s first-period class takes place where her students have wanted to be all week — in the kitchen.

Today, McLennan jokes, “is a bit of a gory day.”

Quartets of students wearing bonnets, aprons, and gloves stand around metal prep tables, threatening a whole chicken spread on a cutting board.

One 16-year-old junior works his boning knife carefully, making precise incisions between joints and flesh. “We are removing the entire leg,” he explains.

The student — his first name is Lan, and school officials asked that students’ full names not be published — lives in Albany Park on Chicago’s Northwest Side. He considered applying to North Side schools with better reputations and higher test scores, such as Lane Tech or Lake View.

But Lan ultimately landed at Roosevelt because he thought its popular culinary certification program offered more options. He could be a chef, go to college, or both.

Lan highly recommends Roosevelt for that reason — despite the bad things he’s heard people say about his school.

“I don’t think they know Roosevelt,” he said.

By one important measure, Roosevelt, where nearly 93 percent of students qualify for subsidized meals, looks like a school that might not offer the richest educational opportunities. Less than 10 percent of students there take Advanced Placement classes, the college-level courses that often mark the transcripts of students at schools with more affluence.

At the same time, far more students take AP courses at two other schools in Albany Park, one of the city’s most diverse neighborhoods. Those differences in educational opportunity are put in stark relief through a new interactive database from the news organization ProPublica built using federal education statistics.

Even as Chicago Public Schools has made some historic academic gains, the data show vast disparities in the kind of coursework available to students.

But as Lan’s experience illustrates — it’s vocational education that drew him to the neighborhood school — opportunity doesn’t hinge on just one class, on one measure.

This underscores a critical question confronting principals and top Chicago school administrators alike: What does opportunity look like? And what’s the right balance between classes that boost their schools’ reputations and those that serve their students’ varied needs?

A fresh look at data

In a starkly segregated city like Chicago, Albany Park appears more diverse. Nearly all-white as recently as the 1970s, the neighborhood has become a major port of entry for new immigrants and is now nearly half Latino, with residents who are Korean, Indian, Lebanese, African, German, and Eastern European too.

But even here, three high schools in the area that sit within 10 blocks of one another and share an El stop couldn’t be more different.

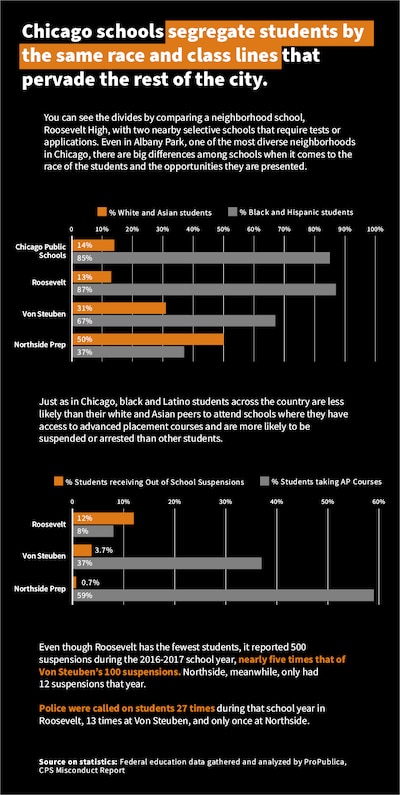

About half of the 1,100 students at Northside College Preparatory High School, a test-in school that is one of the top in the state, are white or Asian. Nearly 60 percent of Northside students take Advanced Placement classes, compared with the district average of 22 percent.

Blocks away sits the 1,800-student Von Steuben Metropolitan Science Center, a magnet high school with a citywide lottery to enter and a separate selective “scholars” program for those with a minimum 3.0 GPA. There, 37 percent of students take AP classes.

Chicago rates both Northside and Von Steuben Level 1-plus schools, its top rating. At both schools, few students are English language learners.

At neighboring Roosevelt High, there are no admissions requirements. Nearly 69 percent of students are Latino, and 28 percent are English language learners. Only 8 percent of the students take AP classes, and there’s no AP math courses or calculus offered.

Such contrasts extend systemwide. Even though the Chicago district is just 14 percent white and Asian, those students have disproportionate access to elite high schools, AP classes, International Baccalaureate programs, and even arts and music education in some neighborhoods.

What to do about those inequities at the school level is far from clear. At Roosevelt, Principal Dan Kramer is working to revitalize the neighborhood high school by improving safety and boosting achievement. He and his predecessors have made progress: Roosevelt is graduating more students than in recent years, up from 56 percent in 2011 to 66.5 percent this year. He is also growing a program that lets students take courses for college credit.

Roosevelt’s enrollment has dropped by more than 400 students since 2014. Two-thirds of its current students take vocational classes, formally dubbed career technical education.

Lan and some of his classmates say they want more courses on aviation mechanics, engineering, digital media, and nursing — classes that will secure them certifications, apprenticeships, and jobs.

Now Kramer, like principals at other underenrolled neighborhood schools, faces a tough decision. To attract and prepare more college-bound students, should the school invest in more AP classes? Or should it provide more career prep — like its popular culinary program that graduates students with kitchen experience and certifications that provide an entre to the food and hospitality industry?

“Pushing students into the AP classes for the sake of saying, ‘look how many kids I’ve got in AP classes’ — I think is really unfair to those students,” Kramer said, “for the sake of trying to make the school look good.”

One way Kramer hopes to attract more students is a pilot “scholars” program that steers high achievers to honors and AP classes. The program is in its first year.

No guarantee of equity

Nearby Von Steuben Metropolitan Science Center, which is considered a high-quality alternative to selective-enrollment high schools like Northside, has come up with its own way to attract students: an honors-level “scholars” program that requires a 3.0 GPA and an application with an essay. It split the school’s population into “scholars” and what students call the “regulars.”

In practice, the tiers mean that access to advanced coursework varies by race.

“It creates a sense that, if you’re a scholar, you deserve more, you’re smarter, you have all of these opportunities available to you, and if you’re a magnet school student, you’re just regular,” said Ashayla Freeman, 18, a senior who lives in Austin on the city’s West Side.

And, she said, while the student body is diverse, “I feel like in the scholars program you see that diversity less and less.”

At Von, 43 percent of the students who take AP courses are white or Asian — groups that together make up on 31 percent of the school. Overall, the school is 56 percent Latino and 11 percent black, but those groups make up just 46 percent and 8 percent, respectively, of AP enrollment.

Friends Jade Trejo Tello, 16, and Itzel Espino, 15, who are both Latino and live in Albany Park or neighborhoods nearby, have had divergent experiences at the school. Both applied for the honors track. Tello, who passed, takes all honors or AP classes and loves geometry and algebra.

Espino, meanwhile, didn’t get into the selective program. She’s still happy with her high school experience — she’s focused on keeping her grades up, so she can become a teacher — but feels that the selection criteria for the scholars program wasn’t entirely fair.

“I didn’t get the chance to be able to show myself, and I know some kids do have troubles that affect their school life and their grades,” she said. “We are not given a second chance to show ‘Oh, I can handle an honors class.’”

Messages seeking comment from Von Steuben leadership were not returned.

Declining enrollment

To have the budget to offer more courses for students like Espino, schools need to attract more students. But to attract more students, schools need a robust menu of courses. It can become a chicken-and-egg proposition.

To boost Roosevelt’s declining enrollment, Kramer has made the choice to market its vocational curriculum. “We’re meeting a demand,” Kramer said, emphasizing that many students have family members who work in child care, preschools, restaurants and health care — classic vocational education tracks.

“Families see there’s a lot of career opportunity without much investment in postsecondary education,” he said. “In working-class neighborhoods in Chicago there’s an appreciation that these are growth industry areas.”

But if a school like Roosevelt offers culinary courses but no AP math classes, that could limit students’ choices in other ways. Advanced courses can signal students’ readiness for college work, and passing scores can earn students college credits, though research isn’t conclusive on the benefits if students don’t pass the tests.

P. Zitlali Morales, an associate professor of curriculum and instruction in the College of Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago, argues that vocational courses should be available throughout the city— but it’s important to not allow that path to become an either/or choice for students.

“Right now, certain vocational opportunities are offered at certain schools for certain kids, and right now those are the kids who are English learners and also the children of immigrants,” she said.

For the first time, Chicago has hired someone whose job it is to wrestle with that and other tough questions of race and opportunity. Schools chief Janice Jackson has tasked new Chief Equity Officer Maurice Swinney with tackling the imbalance of opportunity districtwide for black and Latino students.

Jackson also has offered neighborhood high schools the chance to apply to offer specialized programs, including vocational offerings, arts programs, dual language certifications, or designations such as International Baccalaureate, magnet or gifted programs.

The competitive application lures principals with a pledge: Selected schools will also win money to cover the expenses of new teachers or certifications. It’s meant to help principals like Kramer to avoid having to make such stark choices about programming.

Kramer says he’s planning to propose applying for a dual-language academy. Students would have the opportunity to earn a prestigious seal of biliteracy, which will allow them to waive two years of a foreign language requirement at any Illinois public university.

Letters of intent are due Oct. 26. Kramer sounds almost giddy at the prospect.

This story is part of a partnership between Chalkbeat and the nonprofit investigative news organization ProPublica. Using federal data from Miseducation, an interactive database built by ProPublica, we are publishing a series of stories exploring inequities in education at the local level.