Daniela Rendon knew she wanted to be a teacher after her junior year, when she met Nancy Guzman, her Spanish instructor at Chicago’s Back of the Yards College Preparatory High School.

Guzman taught Rendon not only to regard her native Spanish as an asset and not a deficit, but also to think critically about history and stereotypes. And Guzman served as an important role model.

“I found someone who I connect to,” Rendon said.

Connections like those matter — but don’t happen often enough in Illinois, where 52 percent of pupils are students of color, and 83 percent of teachers are white, according to new data from the state education board’s Illinois School Report Card. The disparity concerns academics and educators, who say that students benefit when they can identify with a teacher of the same race or ethnicity.

Back of the Yards, a top-rated South Side high school with a student body that’s 91 percent Latino, does better than many schools in narrowing that disparity. But its future depends on bolstering better-than-the-district averages of non-white teachers. Currently, its faculty is about one-quarter Latino, a bigger proportion than in the district as a whole, but the school’s principal, Patricia Brekke, estimates her staff is still about 70 percent white. For her, recruiting native Spanish speaking educators is an essential ingredient in plans to build a dual language program at Back of the Yards — one that would prepare her students to compete in an economy where fluency in Spanish is increasingly valuable.

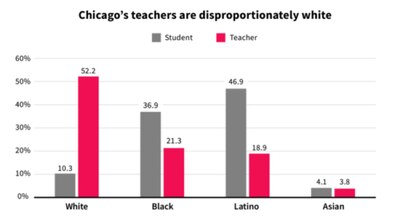

In Chicago Public Schools, where 9 in 10 are students of color, 52 percent of teachers are white. Chicago’s teaching ranks — which are 19 percent Latino and 21 percent black — are the most diverse among the state’s 10 biggest school districts, but they still have a long way to go for faculty to better match up to students.

Research suggests that students show up to class more often, test better and are more likely to graduate when they have teachers from the same ethnic group.

The Illinois School Report Card doesn’t list teacher ethnicity as the school level, but state education board spokeswoman Jackie Matthews wrote that the state will consider adding that to future report cards.

The benefits of diverse teacher workforces

Studies show that having teachers of color benefits all students, who can see adults of color in authority positions, not just stereotypical negative characterizations often portrayed in the media. Research also shows better academic and social-emotional outcomes for students of color, a higher likelihood that they receive culturally responsive education, and reduced likelihood of being stereotyped or suffering implicit bias when they have a teacher from a similar cultural background.

Another aspect is retention.

“Teaches of color are more likely to work and remain in hard-to-staff schools than white teachers,” said Rebecca Vonderlack-Navarro, manager of education policy and research at the Latino Policy Forum. “When people come from the community and understand it, it’s not like this cultural shock. It sounds like they really have an ability to see things from an asset based lens, a strength-based perspective.”

Matt Lyons, chief talent officer at Chicago Public Schools, said the district wants all students in Chicago to have access to a teaching workforce as diverse as the city itself. But he acknowledged the district faces major challenges in shifting racial balances, the biggest being that fewer people are training to be educators.

“We’re fighting for a larger and larger share of a shrinking pie,” Lyons said.

Numbers from teacher prep programs support his observation.

About three in four teacher candidates in the state identifies as white — a proportion that has remained constant for a while. At the same time, the percentage of students of color in Illinois has grown from 46 percent to 52 percent since 2008.

Pipeline problems and solutions

The district touts several tactics for boosting the number of Latino and black teachers. Chief among them is a teacher residency program launched last year with National Louis University and Relay Chicago that recruits heavily from paraprofessionals — who tend to be a more diverse group than new teacher candidates. The district also is relaunching teaching academies at high schools that prepare students to pursue an education degree.

It’s looking to private partnerships, too, by contracting with nonprofits such as Golden Apple and Grow Your Own Illinois to help build a pipeline of teacher candidates of color.

Robert Muller, dean of the National College of Education at National Louis University, has sought to help the school district diversify its student body in part by helping train teacher aides and paraprofessionals to become teachers. But, he said, the pipeline needs work.

“I would hypothesize we have a pipeline that is leaky in a bunch of different places,” he said. “It’s not just getting folks in the pipeline but keeping them there.”

Working harder to retain teachers in their early years by providing more mentoring and support and improving work conditions would both reduce the teacher shortage and increase diversity, Muller said.

The state board of education is working with other states to diversify teacher demographics and ensure teachers of all races practices culturally responsive teaching, according to spokeswoman Matthews. She also said the state assists teacher prep programs in developing recruitment and retention plans for diverse educators.

This month the state approved to fortify and broaden its teaching workforce, by stepping up mentoring, creating more paths to a credential and eliminating a basic-skills test for mid-career candidates.

Elizabeth Todd-Breland, an assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago also suggested that the district give its own graduates hiring preference, and said the district needs a drastic plan to reverse the steep decline in black teachers since 2000 and boost the numbers of Latino teachers. Nearly half of all district students are Latino.

Vonderlack-Navarro recommended recruiting district students who receive the seal of biliteracy, among other strategies for building a strong pipeline of Latino teachers.

“We need to be thinking about this at all levels,” she said. “If the teacher workforce is going to reflect the student body, we need a minimum of about 5,000 more Latino teachers.”

But she and other experts emphasized the importance of improving the conditions and narrative around the teaching profession, and connecting students with the idea of teaching as early as high school.

“I just want my kids to feel comfortable”

At Back of the Yards, Guzman recalls how, as a high school student, she too aspired to be a teacher, like her protege Daniela Rendon. But that was because Guzman lacked any connection with the mostly white teachers at her Little Village school, not because of a special bond with a teacher. She wanted to come back as an educator in Latino communities like the one where she grew up.

“I just want my kids to feel comfortable, I want them to feel connected and for them to see that whatever we are doing in class is relevant,” she said.

Guzman and other Back of the Yards teachers are working to build a dual language program with at least 50 freshmen next fall, adding similar numbers in each of the three following years. The initiative could help Back of the Yards compete for students with other high-demand schools.

Graduates of the program would hopefully leave Back of the Yards with the State Seal of Biliteracy on their diploma. The seal certifies attainment of a high level of proficiency in one or more languages in addition to English, and provides a credential to entice both employers and universities.

Principal Patricia Brekke has identified seven of 14 teachers she’ll eventually need, including Guzman. Amid an acute teacher shortage, she faces the challenge of ensuring the teachers have special language certifications and coursework. The school district has been supportive and is connecting her with universities producing likely candidates. The principal said she’s going to continue to recruit bilingual teachers, preferably Latino, “so that students receive instruction from native speakers.”

She’s also staying close to graduates at the predominantly Latino school who say they want to be teachers.

“They are coming back to say this teacher made such an impact on me, I want to be a math teacher, and I say — come back and be a math teacher here,” Brekke said.

“We want kids to be whatever they want to be,” she said. “But if they want to be educators, they should come back and do that service in communities where they feel like there was a profound impact made on their lives.

“So we keep talking about what that looks like, to come back home.”