At a forum designed to explore solutions to putting top-rated schools and programs within reach of all Chicago students, residents of Greater Grand Crossing pushed Chicago Public Schools to help dispel stigmas they say makes their campuses a tough pitch to prospective families.

Nearly 100 residents, educators and school district leaders convened Thursday at Chicago Vocational Career Academy High School to review a district report on enrollment trends, school quality options, parent choice and program variety.

Known as the Annual Regional Analysis, it has spurred conversations about school quality, barriers to education equity — and fears of painful decisions to come amid an ongoing enrollment crisis. The school district presented hard numbers behind the problematic trend of shrinking neighborhood schools.

In a part of the city where students have one of the city’s longest commutes to school, district officials reviewed evidence of a troubling dynamic: students skipping over their neighborhood school and traveling long distances for other options.

The district’s chief school development officer, Hal Woods, drew from the report’s data about school quality, enrollment trends, choice patterns and programs, and reviewed data on the Greater Stony Island region, one of 16 planning areas defined by the city.

The region includes 10 communities in addition to Greater Grand Crossing, including South Shore, South Chicago, Chatham, Avalon Park, and Roseland. While clusters of middle class and affluent residents live in the area, most neighborhoods in the region have lower median household incomes.

As of last school year, when the analysis was compiled, the Greater Stony Island Region had about 24,000 students, most of them black, at nearly 50 schools.

Like in other parts of the city, many of the schools with neighborhood attendance boundaries suffer from underenrollment, bad reputations, a lack of of high-demand programs and low school quality ratings. But plenty of families are also skipping over top-rated schools.

Attendees Thursday representing neighborhood schools said they don’t have shiny new buildings, or the finances or resources to wage a robust marketing campaign as many charter schools do. They sought district support to combat bad reputations and to inform other parents – beyond school ratings – about the good things happening on their campuses.

“Are students choosing schools in their region? I think this is a really critical slide to look at for folks in this room,” Woods said, lingering on a chart showing average commute times for students across the city.

Local elementary school students commute an average of 2.6 miles, the farthest of any region in the city. At the high school level, Greater Stony Island is tied with the Far Southwest Side region for the longest student commutes, an average of 5 miles compared with the citywide average of 3.6 miles.

In the past four years, the region has lost at least 2,600 district students – or 10 percent of its student population compared with a 6 percent drop citywide. The region had more than 4,200 unfilled, top-rated elementary school seats, but there are only about 450 unfilled Level 1 high school seats.

Of the four high schools in the area with neighborhood attendance boundaries, only Chicago Vocational is in good standing, according to the district’s school rating system. The other three neighborhood schools, including Harlan Community Academy High School and Hirsch Metropolitan High School, all suffer from low ratings and dwindling enrollment.

Meanwhile, the only schools in good standing or building enrollment are charter schools like Gary Comer College Prep with the Noble Network, or South Shore High School, a district-run selective enrollment school, and all draw attendance from across the city. Some attendees accused the schools of siphoning students from neighborhood schools with attendance boundaries.

But nearly two in three high school students leave the region altogether, “which is the high for all ARA regions,” Woods said.

In small discussion groups, attendees questioned how well school ratings actually convey quality, emphasizing that economic development, safety of the school neighborhood and the climate inside also factor into parents’ decisions.

Many said that the district should help schools suffering from stigma communicate their accomplishments and benefits, whether via social media, websites or billboards.

“We have wonderful things to offer — how are we going to market that at CPS?” said Wenda Royal, community school resource coordinator at South Shore Fine Arts Academy, speaking for a group of participants.

“There’s perceptions of schools that go back 10, 15, 25 or more years, that are no longer accurate,” Woods agreed.

Sherretha Richardson, a parent of three district students at Carnegie, Kenwood and Bouchett who lives in the East Side community, said marketing is especially important for schools whose ratings might not reflect a school’s successes.

“You look at Chicago Vocational, and you see a Level 2-plus. But you have Level 1-plus administration and teachers as far as their effort, their energy,” she said.

She said the district has to do a better job of engaging parents with technology.

“This meeting here, for the parents that couldn’t come out, there should have been a webinar, they should have had it on the internet, where the parents could have chimed in and actually heard what was going on,” she said.

District CEO Janice Jackson was paying attention.

“One of my commitments is really to restore the credibility and the integrity of our school system, and it starts with sharing more information, and that’s what this event is about tonight,” Jackson said in opening remarks.

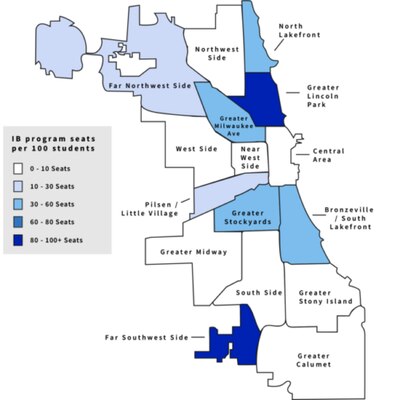

She’s begun an initiative that allows schools to request programs like the International Baccalaureate on their campuses. The alternative, she said, “is what has occurred for too long, which is the people in charge, me, my team, sit around a conference table, look at a map, look at data, and make decisions about who should get what.”

“What I say to some of the people who have a problem with this is that you can demand community engagement, but you cannot tell me how to engage the community,” she said. “And I think this is the right approach, I think this is what we need to do to make sure everybody feels like they have a fair shot.”