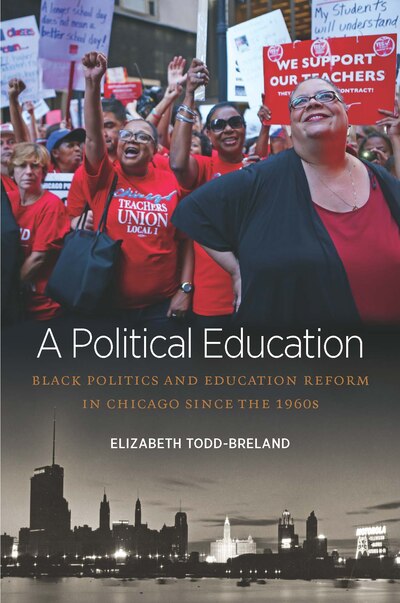

This fall marks 55 years since a massive student boycott to protest segregation in Chicago schools, and six years since a strike aimed at improving conditions for teachers. A new book by University of Illinois at Chicago historian Elizabeth Todd-Breland examines that history that unites those two events — and how that history relates to the racial politics of education policy change in Chicago. This excerpt is from the epilogue of “A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago Since the 1960s.”

In the fall of 1968, a black student boycotted Kenwood High School on the South Side of Chicago for several consecutive Mondays. She did not act alone but was part of a movement of tens of thousands of black students at high schools across the city.

These were not spontaneous walkouts. Her father drove her and her friends to and from organizing meetings where the students outlined their demands for more black teachers and administrators, the incorporation of black history into the curriculum, and improved facilities at predominantly black schools in the city. Her parents worried that she would be arrested but encouraged her and supported her activism. Collectively, these boycotts nearly shut down several predominantly black schools in the city and compelled the superintendent of schools to concede to a number of the students’ demands.

In 1968 this lone student’s voice would not necessarily have stood out among the many young voices of protest in the city. In the 2010s, however, it would be difficult to miss her. This high school student was Karen Lewis (née Jennings), future president of the Chicago Teachers Union and the face and voice of the 2012 Chicago teachers’ strike that once again brought the city’s education system to a halt and elicited concessions from previously intractable city authorities.

Karen Lewis’s political trajectory maps onto much of the history documented in this book. Her parents were black migrants to Chicago who became CPS teachers. While not on the front lines of black teacher organizing, her parents were part of a generation of black educators who struggled against racist barriers to certification and leveraged the hard-earned benefits of unionization for employment gains.

Lewis attended Kenwood, a high school born of desegregation debates during the mid-1960s and founded as an intentionally integrated school. But Lewis’s protests at Kenwood in 1968 were for Black Power, not integration.

When she first started teaching chemistry in CPS in the 1980s, Lewis admired [Chicago’s first black Mayor] Harold Washington and CTU President Jacqueline Vaughn as leaders and symbols of black political power, but she wasn’t particularly involved in the union. Lewis’s political trajectory underscores the permeability of different black political ideologies and the importance of understanding black political perspectives historically, intergenerationally, and relationally, rather than oppositionally and out of context.

Lewis benefited from the earlier struggles of black teachers, but the bulk of her teaching career during the 1990s and 2000s coincided with the decline in black teacher organizing. Lewis worked at two selective enrollment schools: majority-white Lane Technical High School on the North Side and majority-black King College Preparatory High School on the South Side. She supported the idea of using magnet and selective enrollment schools to promote integration but also acknowledged the failure of that strategy.

Mayor Richard M. Daley had brokered labor peace with the CTU while stratifying public schooling with new charter, selective enrollment, and magnet schools. In 2008, dismayed by increased privatization and attacks on public education, Lewis started attending reading groups, speaking out at Board of Education meetings, and working to restrict charter school expansion with a new CTU caucus, the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators. Lewis recalled that working with this group “reminded me of my student activism days in the sixties, so I felt like I was right back to where I started from. It was just like this full circle thing.”

The emergent Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators, initially organized by white leftist teachers, participated in citywide progressive coalitions and organized alongside parent and community groups across the city that were pushing back against school closings, the proliferation of charter schools, and issues related to racial and economic inequality that impacted CPS families, the majority of which were low-income black and Latinx families.

In 2010, CTU members voted to replace the by-then complacent CTU leadership with Karen Lewis and the other members of the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators. This signaled a renewed commitment to the type of community organizing forged by Lillie Peoples and other black educators during the 1960s and 1970s. The insurgency of the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators developed from the ground up with teachers, parents, and community members working together. Teachers were once again organizing in the communities where their students lived, fighting back against city education reform plans that disproportionately impacted black communities.

As a primary antagonist of the corporatist regime in the city, Lewis’s trajectory is firmly situated in Chicago’s long history of black protest politics and community organizing. However, running parallel to this history is the formidable history of more top-down autocratic political and corporate power.

Nationally, Republicans and Democrats have come together to support neoliberal education reform policies. These policies encouraged reforms that prioritized competition, privatization, school closings and “turnarounds,” charter school expansion, and a reliance on standardized testing. Democratic president Barack Obama, a Chicagoan and the first black president of the United States, ran on a platform of change in 2008. However, in the realm of education he largely advanced the policies of his predecessors, nationally and locally: Republican President George W. Bush’s 2002 No Child Left Behind law at the federal level and Democratic Mayor Richard M. Daley’s Renaissance 2010 education reform policies in Chicago.

Together these policies opened the door for high-stakes testing, school closings, and the expansion of “school choice” through charter schools. Obama appointed Arne Duncan, CPS CEO and Paul Vallas’s successor, to serve as the U.S. secretary of education, further elevating Chicago’s corporate-style education policies as a model for education reform efforts nationally.

Duncan oversaw Obama’s major education initiative, Race to the Top, which mirrored on the national level many of the policies that Daley and Duncan had administered in Chicago. Race to the Top required states looking for federal education funds to compete, and emphasized new standards and accountability measures, charter school expansion, and test-based assessment of teachers and schools. While Chicago policies and officials contributed to the Obama administration’s national political agenda, Obama administration officials also cycled back to Chicago—most significantly Rahm Emanuel, Obama’s White House chief of staff.

Buoyed by Obama’s blessing, Rahm Emanuel was elected mayor of Chicago in 2011. Emanuel furthered Mayor Daley’s Renaissance 2010 plans, embracing corporate education reform and “school choice” plans that opened new charter schools and “turned around,” consolidated, or closed more than 150 public schools, including the closure of approximately 50 schools in 2013— at the time the largest intentional mass closure of schools in recent U.S. history.

In engineering the school closures, Emanuel argued that the logic of corporate reorganization and the market necessitated right-sizing measures to remedy the city’s failing school system. However, Emanuel and his school officials toggled inconsistently between justifications for closing schools based on under-enrollment or “under-utilization” and closings because of academic underperformance.

As had been the case for decades, black students, parents, and communities were dissatisfied with the status quo in many of their under-resourced neighborhood schools. However, they questioned why the schools had to be closed instead of improved. The CTU and community members also questioned definitions of under-enrollment that assessed full utilization at over thirty students to a classroom. In accounts by city and school officials, the history and policies that displaced and depopulated black communities and produced under-enrolled schools were erased.

Adapted from A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago by Elizabeth Todd-Breland. Copyright © 2018 by Elizabeth Todd-Breland. Published by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher.