As the acrimonious teacher strike against Acero charter schools wound down its fourth day, both sides ratcheted up pressure, neither giving any indication of backing down.

The charter network sought a court order to halt the strike, and filed a federal complaint claiming that the strike was illegal.

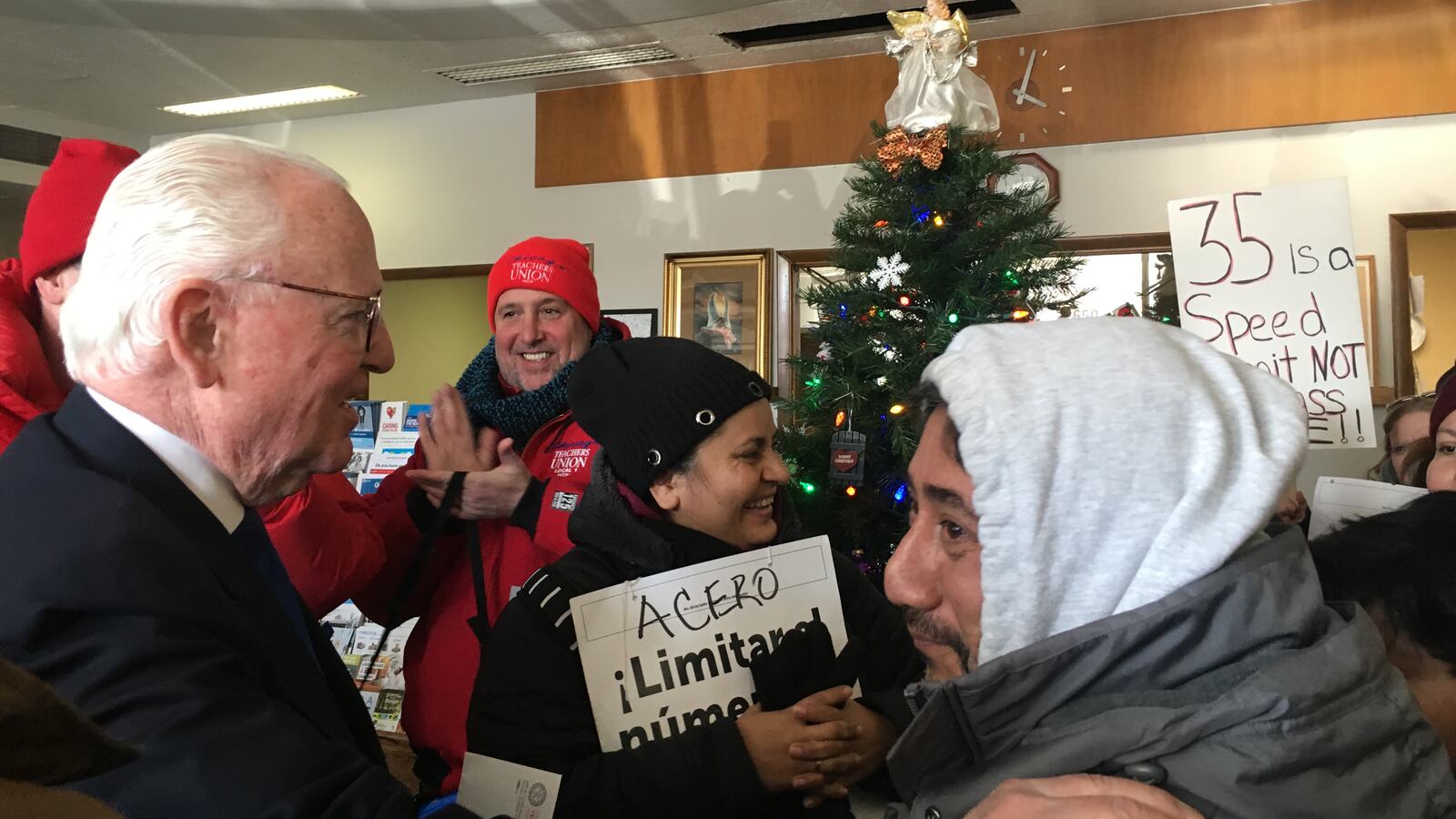

Meanwhile, powerful Alderman Ed Burke, who represents areas heavy with Acero schools, addressed strikers who had marched into his office Friday.

“My heart is with you,” Burke told them. He promised to speak with Acero CEO Richard Rodriguez in an effort to end the strike before Monday, according to both Burke’s office and Acero.

Some 30 teachers and parents wedged into the foyer of Burke’s office between a lit-up Christmas tree and a statute of a horse wearing a green beanie labeled “Ald. Ed Burke.”

They demanded that he use his clout to pressure Rodriguez to agree to teachers’ contract demands, among them smaller class sizes and better compensation for teachers and paraprofessionals. Later Friday, Acero issued a statement confirming that the two, political allies, had met. The network did not explain the content or nature of the discussion.

About 500 teachers have been striking since Tuesday, with 7,500 students out of school. Seven of Acero’s 15 schools are in Burke’s ward.

Acero filed an unfair labor practices complaint against the Chicago Teachers Union and is appealing to the National Labor Relations Board to halt the strike. The charter management organization also sought a temporary restraining order to force teachers back to work. You can read the NLRB complaint below.

In response, CTU President Jesse Sharkey said in a press release, “Acero’s management is desperate and our pressure is working.” He insisted that the strike is a legal protest over wages and working conditions.

In response to strikers’ accusations that Rodriguez is uninvolved in the negotiations, Acero also issued a statement insisting that Rodriguez had met with management negotiators throughout the talks. Union officials have complained of Rodriguez being absent from the bargaining table.

Acero’s roots

Acero, once the nation’s largest Hispanic charter school operator, sprang from a community organizing tool to build Latino political power on Chicago’s Southwest side.

The history of Acero illustrates how charter schools in Chicago are intertwined in local politics, and how their growth would have been impossible without political support.

The United Neighborhood Organization was founded in 1984 by a Jesuit priest who recognized the struggle of immigrants in Chicago’s fast-growing Mexican-American community. Soon a South Side community organizer named Danny Solis joined and turned the organization’s focus first to local school politics and eventually to citywide influence.

Over the years, UNO’s power in neighborhoods grew as it nurtured local leaders like Juan Rangel, who eventually became CEO of the network. Both Rangel and Solis also ran for aldermanic positions, with Solis eventually winning an appointment in 1995 as alderman of the 25th ward, which encompassed the Pilsen neighborhood.

Rangel, meanwhile, had worked his way to the head of UNO just as then-Mayor Richard Daley and his school leadership team were ushering in an era of school choice in Chicago, and looking for community groups to take up the mantle.

“When charters emerged, UNO was one of the first entries into the charter market,” said Stephanie Farmer, a professor of sociology at Roosevelt University who researches charter school finance. “They did work their political connections to get state funding.”

UNO first proposed two charter schools in 1997. Two decades later, it runs 15 schools spread across both the Southwest and Northwest sides of the city.

Enter Ed Burke. Halfway through an ambitious construction project for a new campus, UNO ran out of money and was forced to turn to its political allies, among them Burke, who helped the network get a $65 million low-interest loan from bankers. Several years later, Rangel supported Burke’s brother in his run for an Illinois House seat.

Farmer called this a clear example of the benefits of political patronage, without which Acero could not have grown as much as it has.

“They became patronage benefactors. It was both a way for UNO to build political power and then also a way for Burke to solidify his relations with the Latino political machine,” she said. “They were the only [charter school] who got as much state money as they did for the buildings.”

Rangel’s tenure at UNO ended abruptly and in disgrace. Accused of nepotism and misusing public funds, and under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission, he quit.

The charter school arm of UNO formally separated from the organization in 2013 and, in 2015, renamed itself the UNO Charter School Network (UCSN). In 2017, it rebranded itself as Acero in an effort to distance itself from Rangel’s misdeeds.

Today, charters in Chicago face a harsher climate than they did during Acero’s initial expansion.

Chicago Public Schools recommended this week that the school board deny all new charter applications for the next school year, bending to the political tide rising against the independently operated public schools. And the state’s new governor, Democratic businessman J.B. Pritzker, said while campaigning that he supported a moratorium on new charters.

But Burke’s ability to call Acero’s CEO and encourage him to come to an agreement shows that politics may still play a significant role in the charter industry.

It also shows a more critical turn both toward machine politics and education in Chicago, Farmer said, “The strikers are highlighting that Burke’s machine doesn’t work for the ward’s children.”