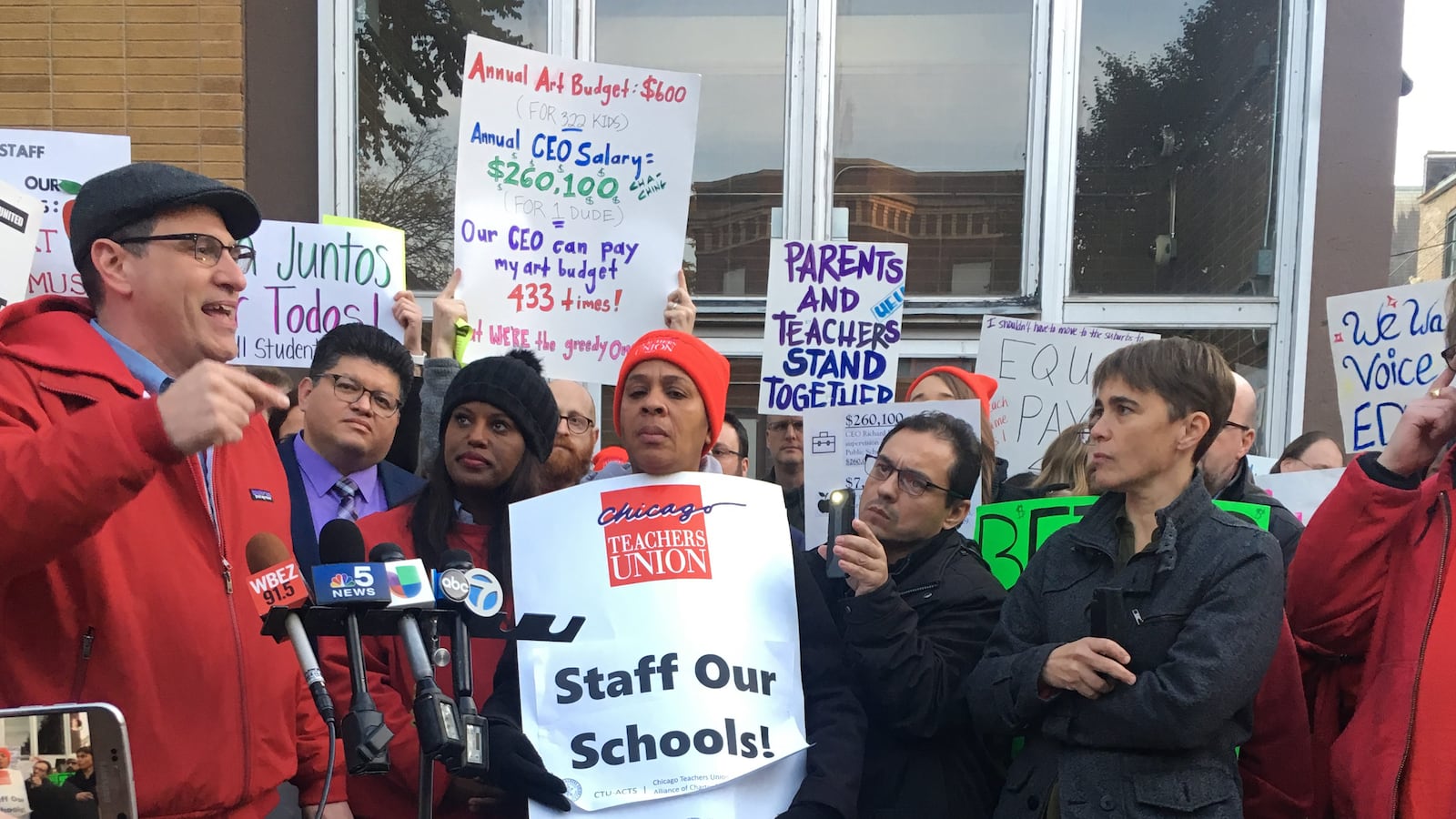

Some 500 unionized teachers joined in the nation’s first charter strike last week, and succeeded in negotiating wage increases, smaller class sizes and a shorter school day. Their gains could foreshadow next year’s citywide contract negotiations — between the Chicago Teachers Union, with its contract expiring in June, and Chicago Public Schools.

“The issue of class size is going to be huge,” said Chris Geovanis, the union’s director of communications. “It is a critically important issue in every school.”

Unlike their counterparts in charters, though, teachers who work at district-run schools can’t technically go on strike to push through a cap on the number of students per class. That’s because the Illinois Education Labor Relations Act defines what issues non-charter public school teachers can bargain over, and what issues can lead to a strike.

An impasse on issues of compensation or those related to working conditions, such as length of the school day or teacher evaluations, could precipitate a strike. But disagreements over class sizes or school closures, among other issues, cannot be the basis for a strike.

The number of students per class has long been a point of contention among both district and charter school teachers.

Educators at Acero had hopes of pushing the network to limit class sizes to 24-28 students, depending on the grade. However, as Acero teachers capped their fourth day on the picket line, they reached an agreement with the charter operator on a cap of 30 students — down from the current cap of 32 students.

Andy Crooks, a special education apprentice, also known as a teacher’s aide, at Acero’s Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz school and a member of the teachers bargaining team, said that even having two fewer students in a classroom would make a huge difference.

“You really do get a lot more time with your students,” Crooks said. “And if you are thinking about kindergarten in particular, two less 5-year-olds really can help set the tone of the classroom.”

In district-run schools, classes are capped at 28 students in kindergarten through third grade, and at 31 students in fourth through sixth grade. But a survey by the advocacy group Parents 4 Teachers, which supports educators taking on inequality, found that during the 2017-2018 school year, 21 percent of K-8 classrooms had more students than district guidelines allowed. In 18 elementary school classrooms, there were 40 or more students.

The issue came up at last week’s Board of Education meeting, at which Ivette Hernandez, a parent of a first-grader at Virgil Grissom Elementary School in the city’s Hegewisch neighborhood, said her son’s classes have had more than 30 students in them. When the children are so young and active — and when they come into classrooms at so many different skill levels — “the teachers can’t handle 30 kids in one class,” she told the board.

Alderman Sue Garza, a former counselor, accompanied Hernandez. She also spoke before the board about classroom overcrowding — worrying aloud that, in some grades at one school in particular, the number of students exceeded the building’s fire codes. (Board chair Frank Clark said a district team would visit the school to ensure compliance fire safety policies.)

While the Chicago Teachers Union aren’t technically allowed to strike over class sizes, the union does have a history of pushing the envelope when it comes to bargaining.

Back in 2012, when the Chicago Teachers Union last went on strike, they ended up being able to secure the first limit on class sizes in 20 years because the district permitted the union to bargain over class size.

They also led a bargaining campaign that included discussion over racial disparities in Chicago education and school closures, arguing that these trends impacted the working conditions of teachers.

“Even if you can’t force an employer to bargain over an issue, you can push them to bargain over the impact of an issue,” Bob Bruno, a labor professor at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, explained.

The Chicago Teachers Union also emerged from its 2012 negotiations with guarantees of additional “wraparound services,” such as access to onsite social workers and school counselors.