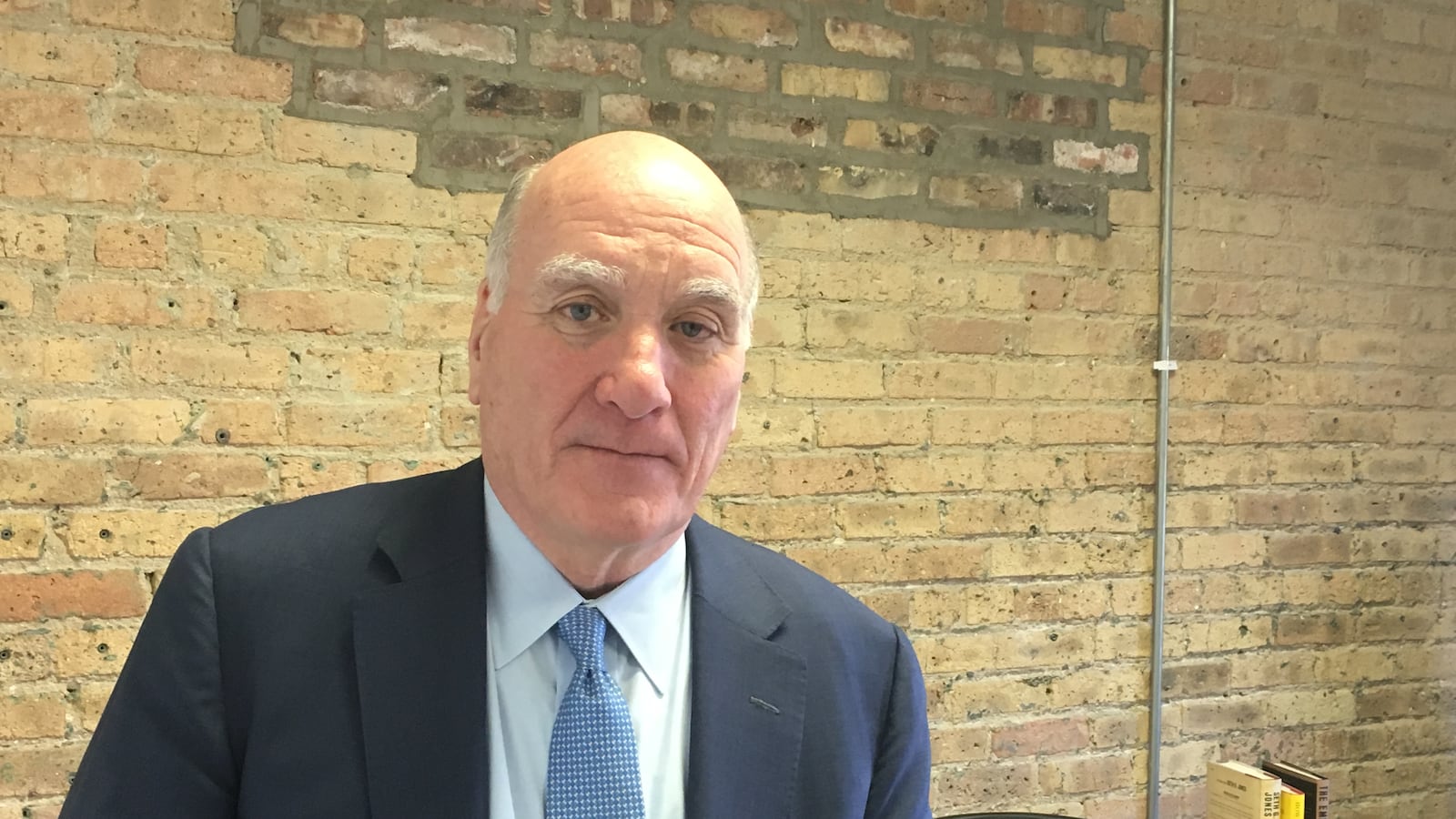

Bill Daley has a big idea.

The mayoral contender on Tuesday proposed merging the $6 billion Chicago Public Schools with the $723 million City Colleges of Chicago.

It’s one of the first disruptive education policy ideas that has surfaced so far in the crowded campaign to replace Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel. The proposal would create what Daley, who faces 14 opponents in the Feb. 26 election, is billing as a first-of-its-kind K-14 public school system.

The proposal, who would require a change to state law, builds on the the district’s Star Scholarship, which already allows Chicago graduates with GPAs of 3.0 or higher to attend city colleges for free. Daley’s plan, by contrast, would offer all graduates the option of two free years at one of the city’s seven community colleges.

Daley, a former banker who served previously as U.S. commerce secretary and White House Chief of Staff, is a brother of the former Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley, and a son of Richard J. Daley, one of the most powerful mayors in Chicago history.

During a press conference outside Malcolm X College Tuesday, Daley touted the merger plan as a way to prepare young city denizens for the labor market, and to help minimize college debt they accrue. Daley estimates Chicago would save $50 million from the merger. But combining two education agencies has some likely challenges — given that both the public school system and the city colleges are losing students, have a history of financial brinkmanship, scandal, and spotty records of student success.

Following the press conference, Chalkbeat Chicago sat down with Daley at his office in the West Loop to dig deeper into his proposal.

Where does the inspiration for this idea come from?

I’ve lived here my whole life, and we’ve seen the struggles of CPS. There’s been some improvement. You see the number of kids going to college increasing, but their graduation from college, four-year college, and preparation for life is really not what it needs to be in this new economy.

Related: Preckwinkle leading in union poll; voters also see Chicago schools on the wrong track

[In the past], we’ve kind of looked at [education] as three phases: grammar school, then high school, and then college, whether it’s a four-year or a two-year. It just seems to me that with the new world we’re in, that we ought to look at this as really K-14, for the point of getting people really ready for life, be that a four-year college or a job. Many jobs today, all you need is maybe two years of college.

The first community college in Chicago was created by CPS in 1911. So it began within that system. Maybe it’s time to put it back together, and have the mindset of the educators being a [K-14] program.

That would be a very big system, though, especially from a bureaucratic standpoint. How would the city manage it?

Well when you combine big systems, you should get efficiencies and effectiveness.

Both systems would bring some baggage to this new relationship. Why does marrying the two make sense?

They’d have baggage standing alone, too.

Obviously, a part of this has to be that it gets better.

I know there are a lot of challenges to [public education] and a lot of questions around it, but that we’ve got to stop doing things the way we’ve done it and think we’re going to get a different result.

I know there will be a lot of naysayers who say you shouldn’t do this, you can’t do this, but it just seems to me that in the 21st century, that we ought to be looking at some of these things very differently.

Both institutions have had their share of financial challenges. So how would the numbers work?

[Financial challenges] are going to be in existence if there’s two systems or one system. Hopefully, there would be some savings.

Where would savings come from?

If you have two widget companies and you put them together, and you have two accountants, you may be able to save on one of the accountants.

So maybe take some of the teachers in high school who are well-trained, and you won’t need as many teachers, possibly. You can look at skills of high school teachers and the city college teachers and professors, and see whether or not there are skills that can be shared between the two of them.

How would governance of this entity work?

You would pick a CEO, obviously, who had the ability to run a different [kind of school system], not just a K-12 or just a City College [system], but you’d get somebody who had the ability management-wise and the experience running a big agency. There are a lot of other big agencies — not only in government, but in the corporate world — that seem to provide pretty good leadership.

There would be a merged [school] board. You’d have some talents of people who know something about higher education, and some that know more about secondary or grammar school and management of a system.

How would the board be chosen for this K-14 system? Would it be elected, appointed by the mayor, or more of the hybrid approach you’ve backed?

I’m not a big believer that elected school boards produce any better system than a [mayoral] appointed one.

I put out a plan on the CPS school board. I’m against [a fully elected school board].

Related: On returning school control to voters, Chicago mayor candidates are split

I think the mayor should have some skin in the game — for the mayor to walk away and say “Oh, I’m sorry, I don’t have anything to do with this” [would be wrong]. And then [we would have] a bunch of people running, raising money, more politicians promising everything, thinking about if they can keep their jobs or win another election.

One of the other issues is non-citizens can’t participate in the election process. There are a lot of kids in the CPS system that are children of non-citizens. They should be able to participate. So what I laid out was developing through the local school councils a system where non-citizens can participate [in the school board selection process], and would end up selecting three people (out of seven total members) who would be put on the board. Basically, the mayor would have to accept them along with his appointments.