Among the leaflets union officials distributed at Chicago’s four-school charter strike picket line this week was one with a bold line at the top: “This is Elizabeth Shaw.”

Shaw is the CEO of Chicago International Charter School network, and her job history and the network’s organizational structure have emerged as top issues in the strike.

Unlike charter networks that run schools directly, Chicago International operates more like a contractor: It hires other organizations to run schools. The network oversees 14 schools run by five different charter management organizations, some of which subcontract management to a third operator.

The unusual structure makes the network an easy target for criticism that unions often levy at management during conflicts: that too much money is going to executives, while rank-and-file workers struggle.

That criticism has become a rallying cry for teachers at four schools on strike, operated by Civitas Education Partners, and for the Chicago Teachers Union, which is working with them as part of a broader push to organize charter schools.

“CICS has decided to put their management greed ahead of student needs,” said CICS Northtown high school teacher Jen Conant, who is among the 180 educators on strike for higher wages for teachers and paraprofessionals and smaller class sizes. “They would rather sacrifice our students than fund classroom resources or pay a living wage to the educators who support our students.”

The criticism also caught the attention of state lawmakers, who raised questions about the network at a hearing in Chicago Friday.

There’s “money in the boardroom but no money in the classroom,” said Rep. Emanuel Chris Welch, a Democrat from Chicago who said he was “not anti-charter” but is distressed that Chicago International is the second charter network to strike this winter. “We need to make sure they reverse that.”

Shaw says the network’s structure is designed to let schools flourish. (Chicago International declined to comment specifically about the flier.)

“The way that we think about CICS is as a container for innovative school models,” she said. “Rather than dictating what the academic model is, what the talent looks like, what the culture should be in our school from our offices at State and Adams, we believe that operators who are more proximate are better positioned to determine academic models.”

That approach represents a small-scale “portfolio model” like those in place in many cities. That’s the approach taken in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, where Shaw worked as an assistant superintendent of the Recovery School District before becoming an education consultant and, in 2016, joining Chicago International.

In Chicago International’s case, the approach is in part a vestige of having launched at a time when the number of charter schools was sharply limited. The network got what’s called a “replicating charter,” allowing it to open multiple schools without getting permission for each one.

Chicago International’s central office handles some aspects of human resources, facilities, and meals, while the five charter management organizations each run curriculum and staffing for a handful of schools.

Chicago International, a nonprofit group, receives funding for students enrolled in all of its schools and distributes that money to the schools, taking a cut for its own management costs. The individual operators — a mix of nonprofit and for-profit groups — also assess fees.

Teachers and the union argue that the fees leave little for the classroom and even less to pay teacher salaries. Teachers at the schools are paid significantly less than Chicago Public Schools teachers.

The network’s structure, Shaw points out, allows for economies of scale that save money — like $150,000 saved by consolidating small operational contracts, including a pest control specialist that visits all of the schools in the network.

“We’ve been really focused on finding these efficiencies,” said Shaw.

The network’s byzantine structure has meant that Civitas’ leaders, not Chicago International’s, have joined teachers and the union at the bargaining table.

“These extra layers of corporate status create several layers of liability separation,” said Pavlyn Jankov, a researcher with the Chicago Teachers Union. “It is an example of evading accountability.”

A 2017 study found that Chicago International students saw moderate declines in math and reading test scores compared with similar students in district schools.

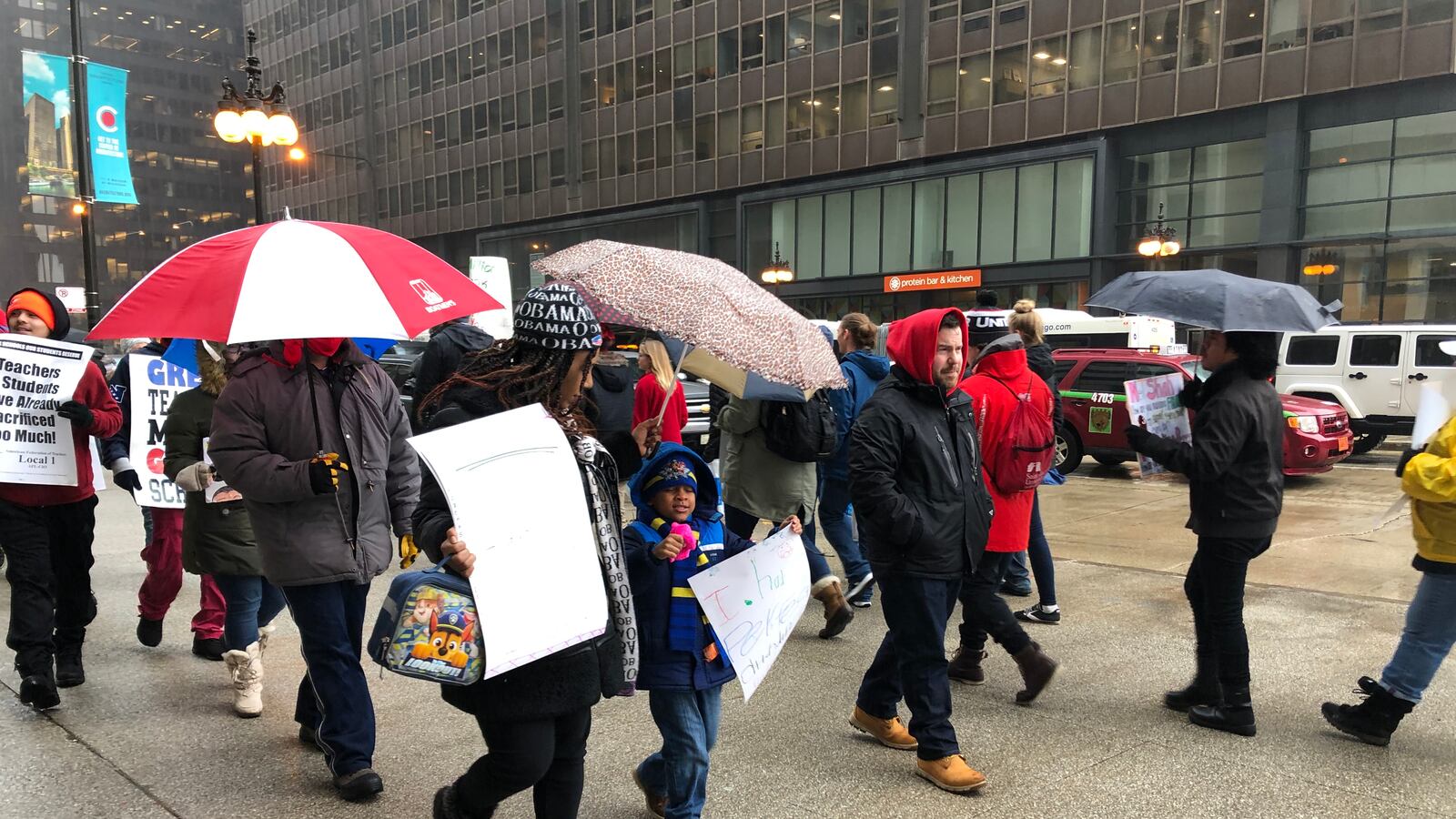

But one current parent who joined teachers on the picket line said the network is working for her child and she wants to see teachers rewarded.

Lakeisha Poole, whose son Isaiah is in first grade at CICS Wrightwood, said the strike had served as an awakening for her because it highlighted the charter network’s complex management structure and the fees paid toward administration that don’t go to the classroom.

Hugging her son’s teacher and shielding her son from the rain, Thursday, she said she was pleased by his recent academic progress. “It’s all from help from my son’s teacher,” Poole said. “These people put their all into our children.”