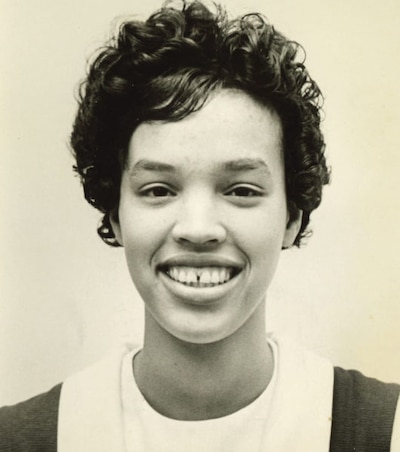

In the first six seconds of Toni Preckwinkle’s latest campaign commercial, scenes flash of the mayoral hopeful as an alderman in City Council chambers, as the poised captain of the county board, and as a smiling teacher greeting children entering a classroom.

A voiceover says, “Before she was alderman or county board president, to hundreds of CPS students, she was Mrs. Preckwinkle.”

“To Toni Preckwinkle,” the voice continues, “education isn’t just policy, it’s personal.”

Related: Who’s best for Chicago schools? A Chalkbeat voter guide to the 2019 mayor’s race

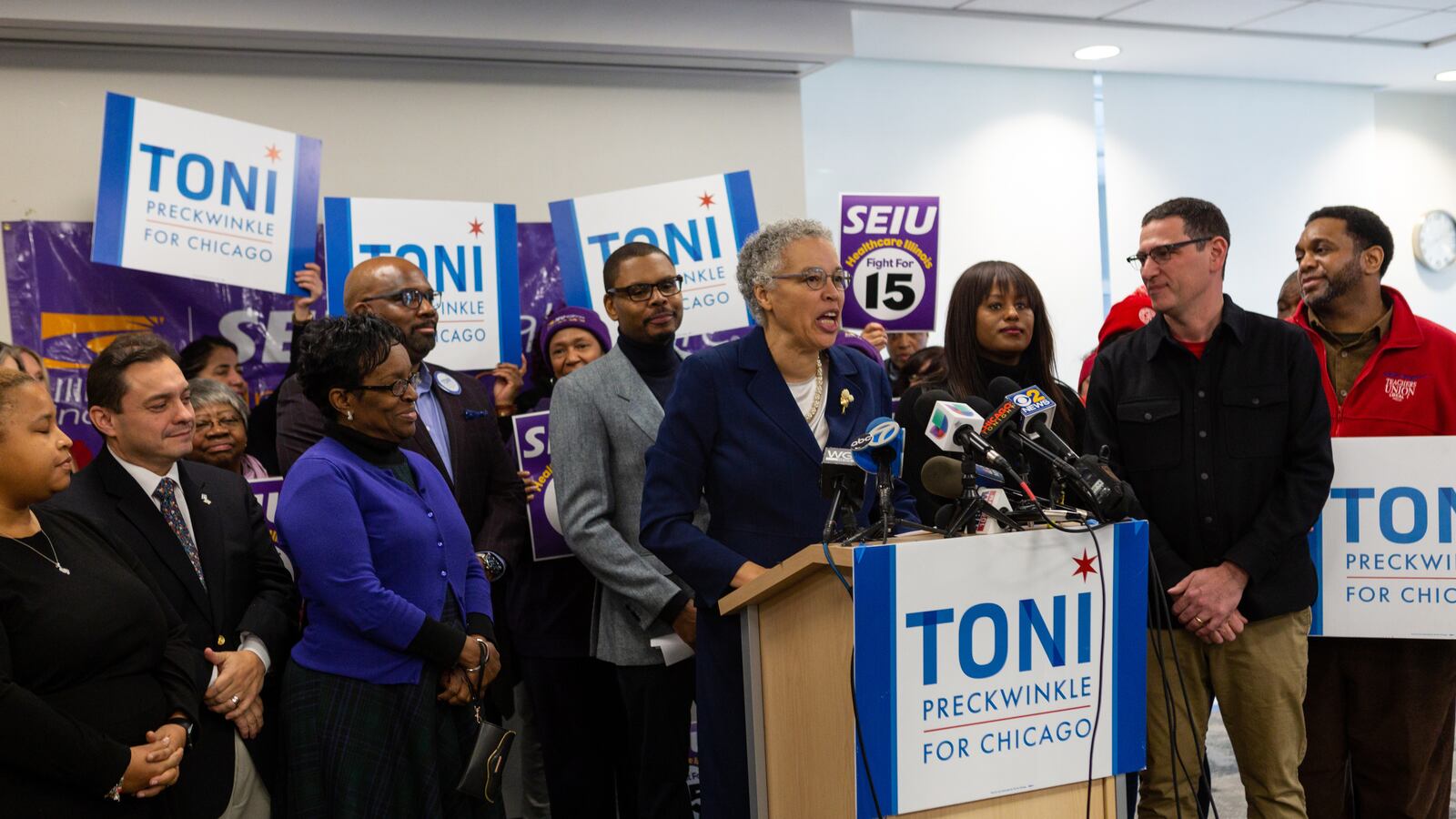

In the crowded and contentious race to be the city’s next mayor, Preckwinkle, who is endorsed by the Chicago Teachers Union, has leaned on her resume as a former public school teacher and longtime Democratic leader, painting herself as the person with the progressive bonafides, experience, and compassion that Chicago needs.

But closer scrutiny of her record shows that at least two of those selling points — her teaching record and her stance opposing new charter schools — are more complicated than her commercials and campaign advertisements suggest.

She taught only one year at a public school before switching to private and parochial schools. She also supported the opening of several charters in her ward during the district’s Renaissance 2010 plan, which aimed to close dozens of underperforming schools and replace them with new ones and quickened the proliferation of charter schools.

“I had schools that were under-resourced that weren’t doing well,” said Preckwinkle, who stressed that the charters she backed are performing well. “I tried to support all our public schools as best I could.”

On a day this week that that Preckwinkle faced scrutiny in the media over her brief tenure at public schools, Preckwinkle sat down with Chalkbeat in her Loop campaign office to revisit her teaching resume and record on schools, and explained why she thinks she’s the best choice for voters who care about the city’s schools.

Preckwinkle, 71, grew up in St. Paul, Minnesota, and moved to Chicago in 1965 to attend the University of Chicago, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in general studies in 1969. She taught history during the 1970-71 school year at Calumet High School, in the Auburn Gresham community on the South Side. That brief stint was the only time she spent in public schools. She later taught at private and parochial schools on the South Side, and at a Montessori school, finishing her teaching career at Aquinas High School, a Catholic school in South Shore, for the 1980-81 school year.

“I loved being a teacher,” said Preckwinkle, who also earned a master’s degree in teaching from U of C in 1977. “Young people are so energetic and enthusiastic and hopeful and optimistic, and it connects you to the future in an amazing way.”

Preckwinkle remembered her sole year at the school district as a tense time rife with labor unrest, and a contentious relationship between teachers and the district. Preckwinkle also recalled that “whenever it rained, water ran down the walls inside the building” at Calumet, which the district would close in 2006 and convert to two charter schools.

Preckwinkle, who worked on her first political campaign at the age of 16, always had her eyes on leadership and political office, she said. After working with various South Side community groups and in the city’s economic development department, she finally got her chance: After two unsuccessful campaigns for alderman, she ousted longtime incumbent Tim Evans (now a chief county judge) in 1991 to become 4th Ward alderman, an area on the South Side that includes the Hyde Park, Kenwood, Oakland, Grand Boulevard and Douglas communities.

Related: Chicago’s mayoral candidates differ on how they’d improve outcomes for students of color

Preckwinkle, who has two grandchildren in Chicago Public Schools, said she wielded her clout to improve the quality of schools and education in her ward. She advocated for an addition to Murray Language Academy in Hyde Park, and lobbied the district to convert former basketball powerhouse King High School into a selective-enrollment magnet high school, one of the first in a predominantly black community.

Preckwinkle also supported the opening of several charter schools in her ward amid Renaissance 2010, including two operated by the University of Chicago. She defended her stance, noting times were different. There were fewer charters than there are today, and less outcry that they were eroding enrollment in neighborhood schools — although criticism emerged from the teachers union and others soon after the Renaissance plan was announced in 2004.

She also defended the university as a non-profit, non-traditional charter operator that invests in the community and education research, and is not one of the big charter operators like Noble.

“Charter schools were envisioned initially as best-practice models for public schools,” Preckwinkle said. “But they were allowed to proliferate to such an extent that they became competitors to the neighborhood public schools, and that proved to be really challenging,” she said.

By 2010, Preckwinkle had embarked on a successful campaign to unseat Cook County Board President Todd Stroger, whose power had been weakened by scandal. During her tenure, she worked toward reducing the county jail population and restoring the county’s fiscal stability, even passing an unpopular soda tax that was later repealed.

As county board chief, she lobbied for laws that raised the age from 17 to 18 for detention in adult jail and narrowed the list of crimes that would allow juveniles to be tried as adults. She also backed a law for automatic expungements of juveniles’ criminal records for certain offenses, to remove barriers to employment and other opportunities that could be stifled by a background check.

Related: Here’s who Chicago mayoral candidates tap for education policy advice

Preckwinkle said as mayor she would continue efforts to keep youth out of the criminal justice system and address racial bias in policing, two issues that local youth activists have rallied around in recent years.

She supports scrapping the police department’s gang database, which critics allege often wrongly profiles people as gang members and overwhelmingly targets black and Latino youth. She also questions whether police should be in schools, and worries about interactions between officers and students contributing to the school-to-prison pipeline.

She recognizes the need for school security, but said if police are going to be in schools, they should be specially trained and barred from meting out school discipline.

“I was a teacher; kids fight, stuff get stolen, things happen, but these are all things we addressed in the school community,” she said. “Schools should handle discipline themselves. If somebody comes to school with a gun, that’s different, but if they are just fighting and doing some of the stupid things kids do, they shouldn’t be put in the criminal justice system for that.”

Related: Police reform could have a big impact on Chicago schools

Preckwinkle’s stance on police in schools, like her approach to politics, has been influenced by her time in the classroom. She says teaching high school history in the 1970s and ’80s was great prep work for politics.

“There’s complicated subject matter you have to translate into language that people can grasp. You’re engaging people, helping them understand why history is important,” Preckwinkle said. “And if you’re up in front of that classroom, it’s like a performance art. Well, a lot of politics is performance, too.”

Here’s a closer look at where Preckwinkle stands on other critical education issues.