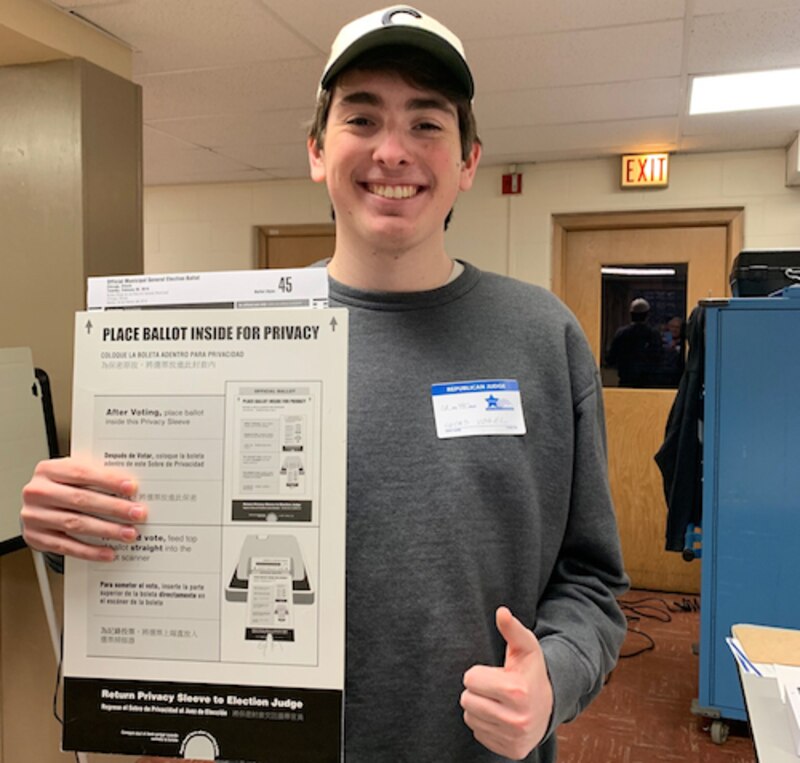

When Lucas Vogel made 18 in December, he knew that he still couldn’t drink, and that he didn’t want to join the military — but he was eager to finally vote.

So he did, casting a ballot for mayor on Feb. 26 along with other Chicagoans, including nearly 19,000 from age 18 to 24. Vogel bucked a trend, as only 15 percent of the youngest voters turned out last week — an improvement compared with the last time Chicagoans voted for mayor in 2015, but a huge fall-off from November, when the age group turned out at a rate of 40 percent to vote in congressional midterm elections and for Illinois governor.

“A lot of people think their vote doesn’t matter, that it’s not going to change anything, that things will always be this way,” said the senior at Jones College Prep High School in the Loop, who backed Toni Preckwinkle. “Sure, voting might not change the entire society or Chicagoland as a whole — but one vote can go a long way in the end.”

Related: How four Chicago educators mine a competitive and historic election for the classroom

Maybe the chilly weather or the crowded field of 14 mayoral contenders dissuaded other young voters, who may have felt underwhelmed by their options, overwhelmed by the decision, disillusioned with the process, unconvinced that their vote matters, or resigned to wait for an inevitable runoff election in April.

With slightly more than one-third of eligible voters casting a ballot in the February election, the low turnout of young voters is not surprising. Illinois also has lagged in preparing young voters. Although the state added a civics requirement to high school curriculum, that doesn’t go into full force until the class of 2020.

The state has stepped up the push for civic education. Beginning next school year, high schoolers will have to take a semester of civics to graduate. On Wednesday, a state House committee will review a bill introduced by Rep. Camille Y. Lilly, a Chicago Democrat, to amend the school code to require public elementary schools to include one semester of civics in their sixth, seventh or eighth grade curriculum.

A sampling of young people interviewed by Chalkbeat offered a window into the mindset of first-time young voters, and ways to spur young voter engagement, from fully embracing civics education to youth-led community organizing and even employing youth at the polls.

Vogel worked as a student election judge at his local precinct polling place, which he helped set up and manage on Election Day as part of a program with Mikva Challenge, a youth-focused civics advocacy organization. Vogel researched candidates’ positions and read media analysis of platforms to inform his vote for Preckwinkle, who he aligns with for her opposition to building a new police academy and her pledge to dismantle the city’s gang database.

“I had this quiet excitement at the polls,” Vogel said. “It was surreal putting the ballot through.”

Elsa Concepcion, a senior at Ombudsman West High School on the Near West Side, said she stays abreast of current issues, and works with the Community TV Network as a youth producer on a public access television show.

She said she began paying even more attention to politics and elections after a rash of school shootings in recent years, especially the February 2018 school shooting in Parkland, Florida, caused her to question gun-control policies and federal lawmakers. Her political awakening grew from a focus on Congress and the White House and evolved into scrutiny of local elected officials and issues like affordable housing, policing, economic development and education. Concepcion, who voted for Amara Enyia, doesn’t think schools teach enough about those issues — or about voting.

“I had to figure out how to register to vote for myself,” she said. “We’re taught about our [Founding Fathers], and why we have democracy, but we’re not taught about how to be civically engaged in our democracy. I think that’s a big curriculum change we need to make.”

With an eye toward the impending state requirement for civics, Chicago Public Schools has expanded its “Participate!” civics curriculum to 89 campuses, about half the public high schools in Chicago. The new state law mandating a semester of civics will require that it include discussions about controversial and current issues, lessons about government institutions, simulations of the democratic process and service learning.

As part of the curriculum, teachers receive training in media literacy, culturally responsive instruction, student-driven inquiry strategies, and race and equity. The idea is that that teachers should foster culturally relevant instruction and facilitate discussions to engage students about issues that touch their lives.

“If you talk to young people their demands are always that school be more relevant and connected to what they care about, and this is a clear place that connection lives,” said Jessica Marshall, one of the architects of the district’s civic education curriculum. “It’s really our job to open space for them to do it.”

Related: Chicago’s mayoral candidates differ on how they’d improve outcomes for students of color

Participate offers a yearlong instructional program teachers can choose to adopt in their classrooms.

“For young people participation isn’t just voting, especially since some kids can’t vote,” said Marshall, who left the district in September for graduate school after three years as director of the social science and civic engagement department.“It’s really about learning about other issues, and engaging with their broader community.”

A spokeswoman for the district emphasized that schools have the option to use Participate or create their own civics curriculum.

Related: Students quiz mayoral candidates about schools and police at Whitney Young High School forum

But some students, like the young activists with Good Kids Mad City, aren’t waiting on the school district. They are helping lead the civics conversation outside of school and educating other young people via outreach, research, and protests about issues.

One of those activists, Alycia Kamil Moaton, a senior at Kenwood Academy High School, voted late on Election Day. She said it was slow at the polling place, but that the election judges there were really excited to see her voting for the first time.

“It was a really powerful feeling to walk out and feel like I made some impact in my city by voting,” she said.

Moaton, who voted for Amara Enyia and praised her campaign for targeting youth, said her mentors at Good Kids Mad City, “didn’t let us go into the election absent-minded.” She said she attended multiple forums, and had to know who the candidates were and what their positions were because she had to teach others in her role of registering voters. The group’s members are mostly black youth. Enyia didn’t win, but Moaton is still inspired by prospect of the city’s next mayor being a black woman.

Moaton has a message for other young people who could didn’t vote but have the opportunity to weigh in on the April 2 runoff between Lori Lightfoot and Toni Preckwinkle.

“It’s better to vote for who you think is a better option, and for them to lose,” she said, “than for you to not vote at all.”