Illinois’ controversial state charter commission could be on its way out after legislators passed a bill to abolish the body, which has the authority to greenlight charter schools rejected by their local districts.

The commission has caught the ire of district officials who argue that districts should have the final say on whether a school is open in their jurisdiction, and of education advocates who see it as a backdoor way to open new charters.

It oversees five Chicago charter schools that the city’s school board voted to close or never approved. Earlier this year, the commission also conditionally approved two new schools: one new school, and one school to remain open, this year.

The bill now heads to the governor’s desk, along with other legislation that would bring increased revenue to the state’s schools by changing the state’s tax structure, legalizing recreational marijuana, and giving the green light for a Chicago casino.

The bill would abolish the nine-person commission by July 1, 2020, transfer authorization of the commission’s nine charter schools to the state Board of Education, and also allow the board to levy a fee of 3 percent of the charter school’s revenue to help cover the cost of overseeing the schools. The commission helps schools obtain a license and funding to operate.

The biggest change would be for any network, nonprofit organization, or individual that wants to open a new school. If they are rejected by the district, they would appeal that decision to a judge, not the charter commission. It’s unclear what court would take on this responsibility.

Currently, charter schools being closed by their districts can appeal to the charter commission, but it’s unclear what the appeal process would be if the commission is abolished.

“We are extremely disappointed,” said Shenita Johnson, director of the commission. “With this vote, the General Assembly is making it more difficult for countless other families to access unique and quality educational options.”

It’s not the first time the future of the commission has been at risk. The only thing that blocked the legislature from severely weakening the commission last year was a veto by then-Gov. Bruce Rauner. The Senate then failed to override the veto.

The bill will hand authority to the state board, which oversaw charter appeals until the commission was created in 2011. “We thought the state board had limited capacity,” said Andrew Broy, director of the Illinois Network of Charter Schools, which lobbied against legislation that would abolish the commission.

Illinois’ new governor, J.B. Pritzker, said last fall during his campaign that he would support a moratorium on charter growth. Asked if he would curtail the authority of the charter commission, he demurred.

Rep. Emanuel Welch, one of the house sponsors of the bill, said he expects Gov. Pritzker to sign the legislation. “It’s a new day. I’m very excited that this bill passed both houses.”

The Republican governor of Tennessee recently wrestled with a similar question, and chose to back off of a proposal to bypass local school boards by creating a new state commission to authorize charter schools.

Since it was first created in 2011, the Illinois charter commission’s oversight has grown to support schools serving more than 4,000 students across the state, according to Johnson. In size of enrollment, that puts it in the top 25 percent of school districts in Illinois.

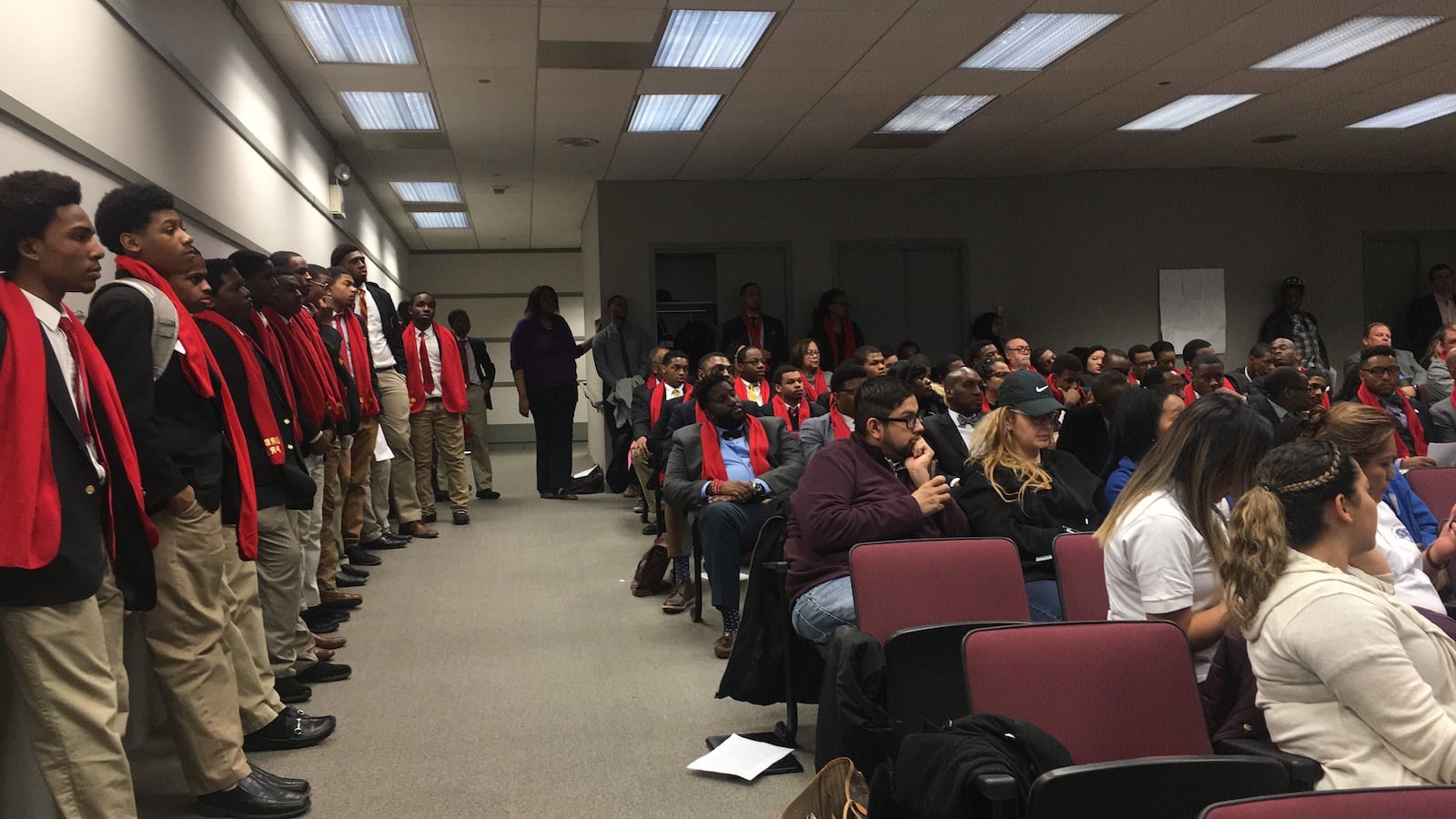

Earlier this year, the commission approved two schools: an all-male Chicago charter school the district was trying to close before their decision was overridden by the commission, and a new citywide school run by charter operator Intrinsic, which wants to replicate its high-rated campus.

Both schools must still meet several conditions before signing an agreement with the commission. If the bill is signed, the commission will not be able to make any agreements with the schools past July 2020.