As a special education teacher whose daily work can range from teaching non-verbal students, or those with high-functioning autism, Kylene Young feels keenly the need for more school social work and special education supports.

But one of the most frustrating aspects of her job is actually a persistent bureaucratic inconvenience: having to clock in and out every day, despite all the extra hours she spends at home writing individual education plans or prepping assignments.

“It’s the No. 1 gripe teachers have, that we as professionals with salaries have to clock in and out every day,” said Young, who teaches at Westinghouse College Prep, a selective enrollment school in Garfield Park.

The first contract negotiations between the teachers union credited with helping spark the nationwide resurgence in teacher organizing and Chicago’s celebrated new mayor are being closely watched — perhaps by none more closely than their 20,000 teacher and clinician members.

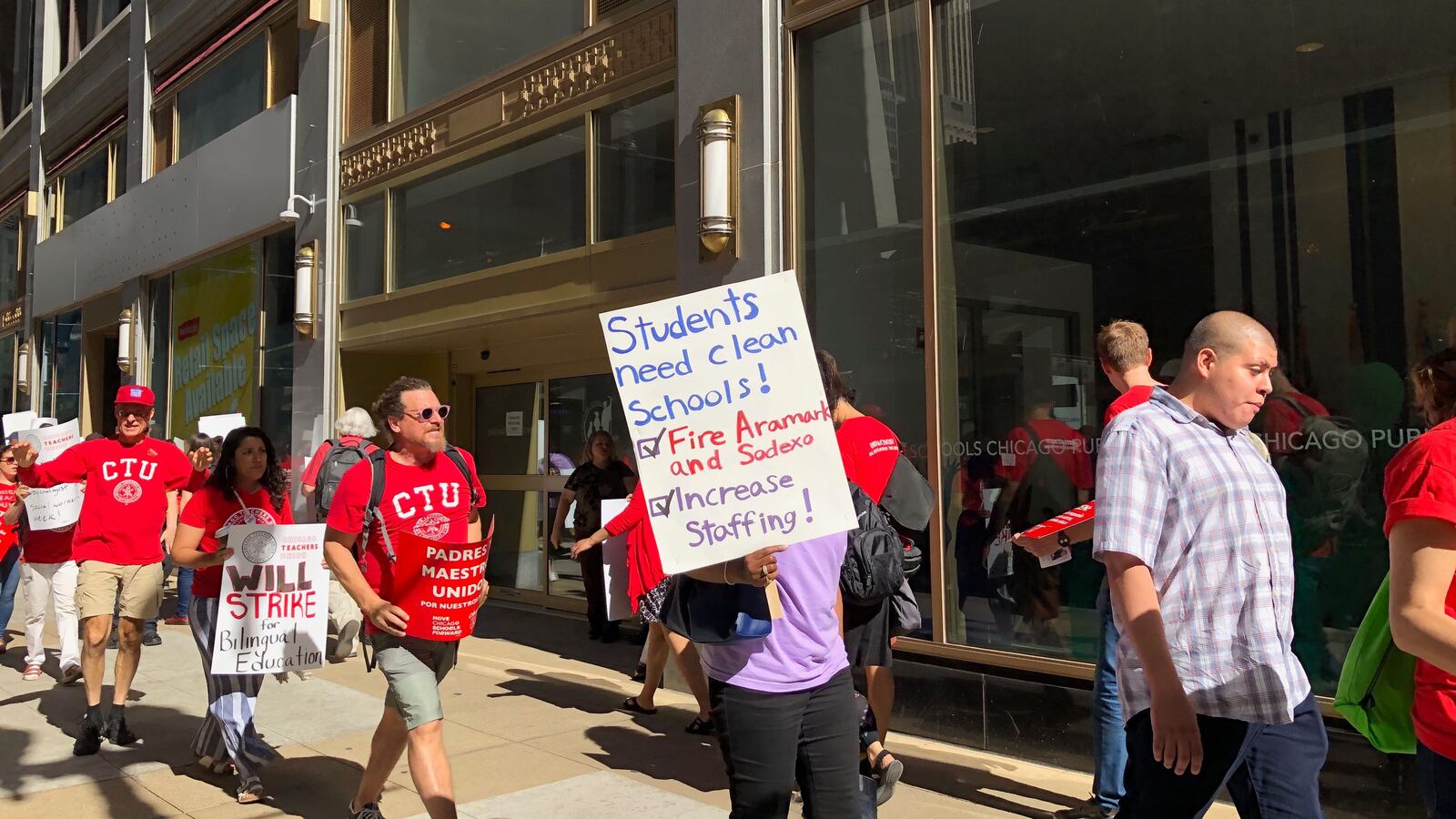

Last week the Chicago Teachers Union rejected Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s first offer on pay for teachers — a 14 percent pay raise over five years — and said it wasn’t enough. They also called again for more clinicians and social workers and an investment in support services such as trauma care. (Read more about Lightfoot’s first proposal here.)

But teachers, entering their second week without a contract, aren’t only watching for the bottom line. For them, the gains and losses of the next contract signed between the union and district officials could be the difference between burning out and staying on another year, between feeling respected and feeling like they are just low-wage workers, and clocking in and clocking out.

Several educators interviewed by Chalkbeat said they support the most well-publicized demands of the Chicago Teachers Union, which has a history of aggressive bargaining that helped set the tone for the wave of wildcat strikes that swept the nation in recent years.

Those demands were developed through a series of member surveys last summer, and include having a dedicated special education case manager in every school and hiring more nurses and social workers. But they also want changes that would help them feel less overworked: better mental health supports for educators themselves, additional prep time,, and less paperwork bureaucracy.

Young compared the paperwork necessary to get a student special education services, to earning a Ph.D. “We shouldn’t be forced to jump through hoops to get essential services for kids,” she said.

Special education services were severely cut under the auspices of former Chicago Public Schools CEO Forrest Claypool and are now only slowly trickling back as the district’s special education program sits under state supervision.

“I shouldn’t have to write a doctoral thesis on an IEP to get a kid services,” she said, referring to an individualized education program that details the educational goals of a student with disabilities, and the accommodations and services they are entitled to.

Patti Freckleton, a preschool special education teacher at Bateman Elementary, said paperwork was one of the most taxing issues for her, noting, “It can be really daunting and stressful, you are writing IEPs at home late at night.”

For some teachers, the lack of funding in their classroom feels only more acute when compared to the money spent on, for example, contracting Armark for janitorial services despite a record of poor performance.

At McKay Elementary in Chicago Lawn, where Valerie Morris teaches special education, she has to ignore rats and mice that scurry across her classroom floor for fear of scaring the children in her class. “Give us the tools that we can use in order to do the job, and for our children to feel like they are human,” said Morris, who has been at McKay for nearly two decades. “Who wants to see rodents in their school? You wouldn’t want that.”

Other issues bubbled up, too. Several teachers who spoke to Chalkbeat were unhappy with a recent rise in health insurance costs.

Teachers said they also want contract changes that give them more time for collaborating with other educators through dedicated professional development days, or extra prep time.

“We have only three or four days built into the school year,” said Leah Stephens, who teaches music at Sor Juana Elementary School. “I think that is something worth fighting for.”

A school’s union’s delegate is tasked with keeping other teachers at their schools apprised of contract negotiations. Major decisions, like whether or not to authorize a strike or approve individual contract provisions, are decided by the union’s House of Delegates, which is made up of representatives of schools and groups of specialized workers, such as social workers.

Most teachers interviewed said they get their contract updates primarily from union emails, but Lisa Love, a third and fifth grade special education teacher at Hawthorne Scholastic Academy notes that she’d like to hear more from the district, too.

As a member of a teacher advisory council to Chicago Public Schools CEO Janice Jackson, Caputo Love said she’s happy that the district has worked to highlight the perspectives of teachers through formal advisory groups. “I have been extremely pleased with some of the big steps CPS has done lately to involve teacher voice,” she said.

For this contract, the union is bargaining in a different political context than it did for its last two contracts, when they were negotiating opposite Rahm Emanuel. The former mayor’s longtime business ties and general disdain for the union (once swearing at its former president during negotiations) made him a formidable but easily caricatured enemy.

Chicago’s new mayor, Lori Lightfoot, ran on a more progressive platform. Several of the teachers Chalkbeat interviewed had voted for her, even though the union had endorsed her opponent, Toni Preckwinkle. Many teachers also have more trust in Janice Jackson than in previous district leaders. That makes the relationship between teachers and leadership less antagonistic than it was in the last two rounds of bargaining.

It has also made some teachers hopeful that they will get their contract demands without a strike, though most of them say they are ready to walk out.

“I think Mayor Lightfoot is going to give us some really key demands to make it really difficult for us to go out on strike. I don’t think it’s going to be enough,” said Emily Penn, a school social worker and union delegate. “If we don’t get the things we need to make our working conditions better, this job is not sustainable.”