During the summer, when the hallways of some Chicago schools are dark, Randolph Elementary School is ringing with children’s voices.

On a rainy morning, Principal Elizabeth Meyers listens to the giggles, the shouts, the sounds of summer. She watches her students paint a mural of dancing blue and red figures. This is a symbol of her philosophy — to give children a piece of the school, a voice in their community: a mural they will walk by everyday, a ceiling tile they decorated that will remain after they leave, a tangible stake in the building.

In a district where principal turnover presents a serious challenge to school communities, Chicago Public Schools is honing in on how to bolster leaders like Meyers by giving them the leadership training and autonomy to determine how to best serve their students.

Meyers just finished a 12-month program as a Chicago Principal Fellow, a partnership between the district and Northwestern University. She trained in leadership at the Kellogg School of Management, designed projects for her school, and met monthly with schools chief Janice Jackson to help shape district policies.

In thinking about strengthening students’ connection to school, Meyers came up with the idea of keeping the doors open year-round. This summer, she expanded and restructured summer school to include more enticing programs for more students.

The timing for the fellows program couldn’t be better, as Meyers’ enters her critical fifth year at Randolph, in a district where 68% of schools reported having more than one principal in five years, according to a 2017 survey from The Fund.

New national research from the Palo Alto-based Learning Policy Institute names a lack in three areas — professional development, decision-making authority, and constructive feedback — as three top factors pushing principals out of the profession.

Chicago Public Schools has launched several programs to address this challenge, giving high-performing principals more autonomy and steering them into fellowships and leadership development trainings like the one Meyers attended. That program does not come with money, but she has been savvy in finding other grant funding and support from nonprofit partners, patching together the resources for a summer program.

Building off of the skills she gained in her fellowship, Meyers identified a lack of summer activities for students as her focus, so she decided to redesign summer programming at her school. Located in Englewood on Chicago’s South Side, Randolph can fill the void for child care when school is out, she said.

“I want to change the narrative of what it means to go to a school in Englewood,” Meyers said. “There is greatness in the community, and that our kids have unique qualities that they can endure so much trauma and pain and still show up resilient.”

The district has a handful of programs for summer learning, such as a freshman connection class for students entering high school, a bridge program for struggling students, and Safe Haven programs at partner organizations offering craft classes and food. But not every Chicago school offers summer programs.

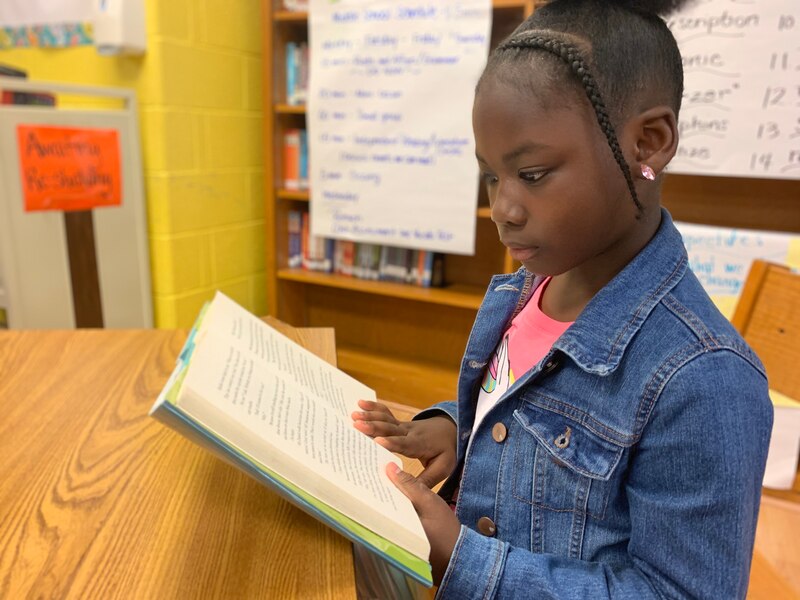

One of Meyers’ students, rising fourth grader D’Ashanti Johnson, is reading above grade-level and wouldn’t necessarily be a candidate for summer school focused on struggling students. But in the Randolph summer program, D’Ashanti gets to practice her reading with older students and explore her passion for cheer and art in the afternoon.

“I like the summer program because it helps me learn and it’s fun,” she said. “I love school because I like being challenged.”

Research demonstrates the importance of continued education during the summer to avoid the “summer slide,” a phenomenon that disproportionately affects low-income students. Without access to enrichment that promotes learning in one form or another, children fall behind over the summer and struggle to catch up when school starts.

This year, Meyers decided to divide the day into academics in the morning and enrichment in the afternoon. She wanted students to associate the program with summer fun rather than remediation or punishment. On Wednesdays, students go on excursions to the beach, the movies, or Chicago’s museums, sites some Englewood students have never seen despite living in the city their whole lives.

Randolph has bursts of orange, red, and yellow on the walls, creating a joyful and welcoming feel to the building. Meyers created a tradition where eighth grade students design and paint ceiling tiles before they continue to high school, leaving “a piece of themselves at Randolph.”

When Meyers walks into a classroom, rising first graders flock to her. Meyers greets each student by name, checking in with one boy to see if he’s doing better after a tough day the day before. She asks what they are learning — number sense, a key skill to succeed in first grade.

Their teacher, Janice Harper, holds up two fingers on each hand; a student mirrors her.

“Now put them together,” she says. “Count them up.”

Harper designed the curriculum herself with help from other educators, including the kindergarten and second grade teachers. She emphasized that Meyers gives her the autonomy and flexibility to cater to students’ individual needs, especially in the summer.

There are only 12 students in the room, and each teacher has an aide in the summer. Harper said she appreciates the extra support. It will be much more difficult when it’s just her and 30 students during the year.

“We get into the classroom and get to know the students,” she said. “The summer is a great time to offer more individualized instruction.”

Harper added that these students will be in her classroom next year, so they can hit the ground running in September.

In the afternoon, students close their books and finish one last math problem before transitioning to activities such as gardening, computer programming, sports, and mural painting.

In the afternoon, students close their books and finish one last math problem before transitioning to activities such as gardening, computer programming, sports, and mural painting. The enrichment is an extension of Randolph’s partnership with a nonprofit group as part of a district-led community schools initiative.

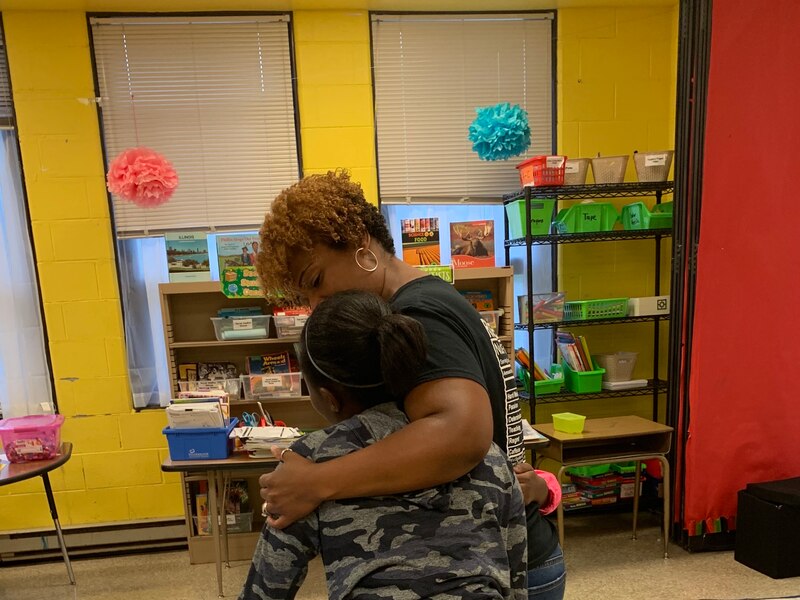

“This program is helping to build self-esteem,” Harper said. “Some of the students that I had the first week, they weren’t saying anything, they didn’t feel comfortable enough … Today, they’re all love, they want to share, they feel comfortable and confident.”

Meyers sees summer as a valuable time to engage students beyond academics. Enrichment activities help students find strengths outside of the classroom that translate when they return to school, she said.

“If you have students that aren’t as confident in academics, they need to have a place that they can shine,” Meyers said. “That’s why the enrichment is key.”

Meyers is excited and hopeful about the summer program. But in the fall, she wants to see results.