Arianna Williams first heard about the Intrinsic charter network’s new high school while on a tour of a neighborhood school last winter. As an eighth grader moving to Chicago from Evanston, she was nervous about the complicated, competitive and often tense journey to find a high school that would be the right fit.

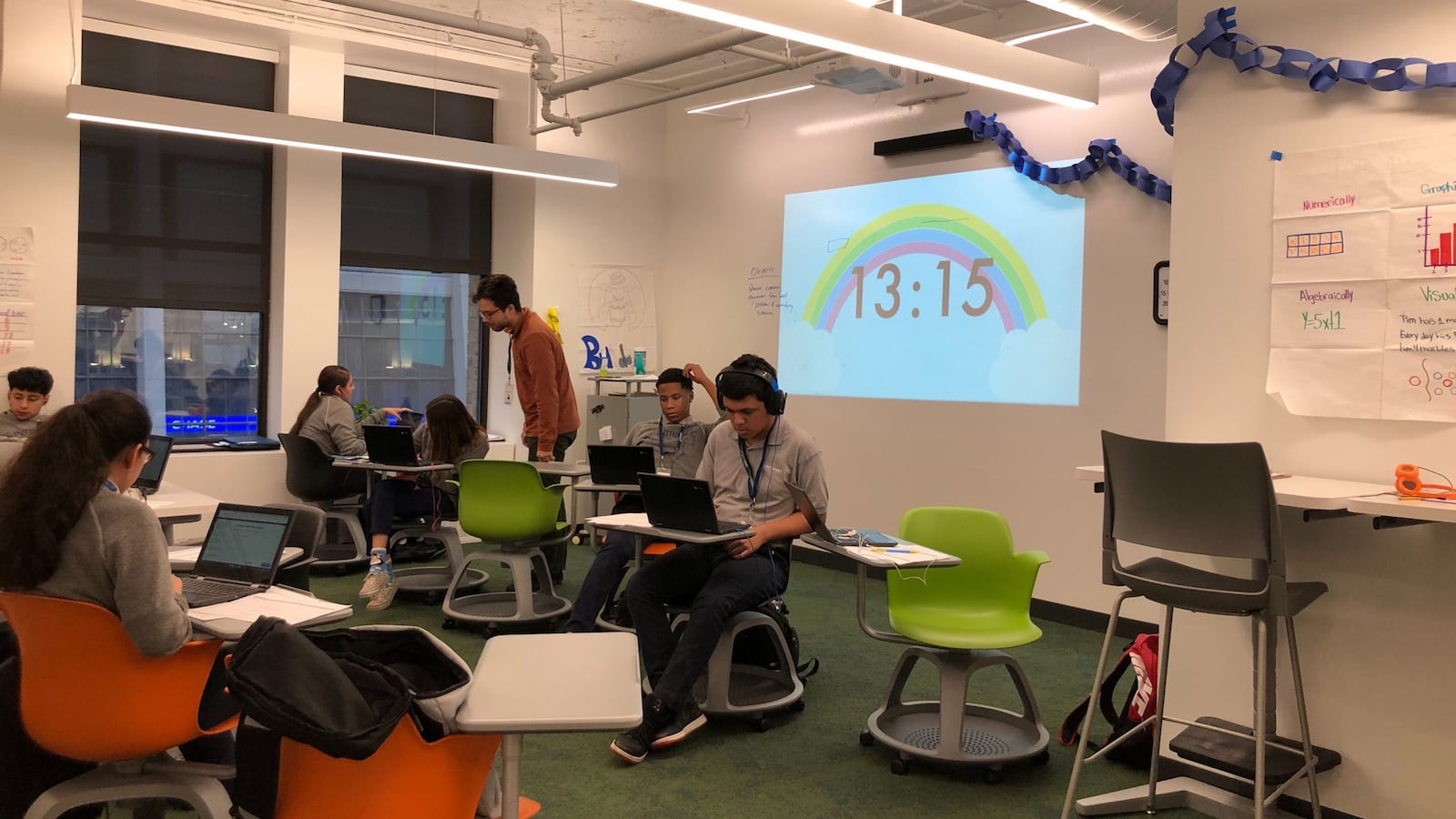

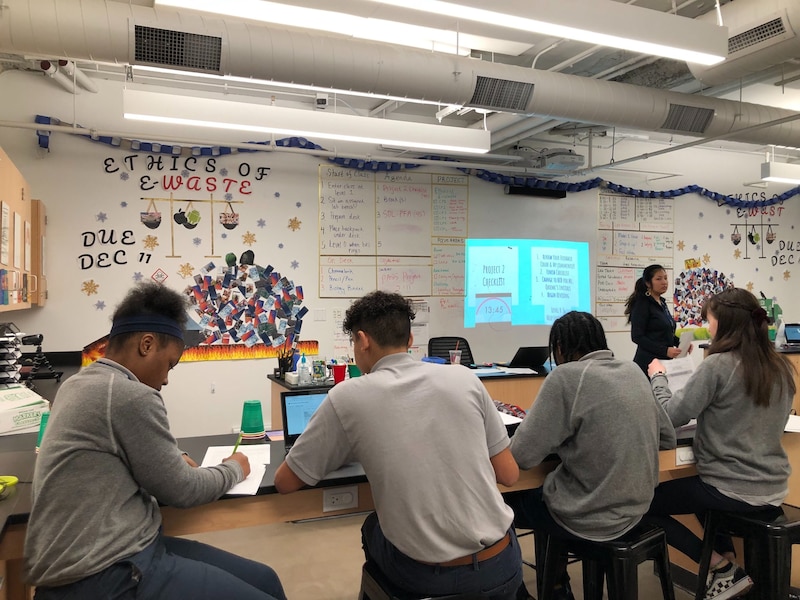

Other students were talking about Intrinsic’s school, Williams said, because it was new, located downtown, drew students from the entire city, and offered an intriguing model of personalized computer learning in rooms called “pods.”

Best of all, students could apply outside of Chicago’s GoCPS application system that asked high schoolers to rank a maximum number of schools, making it essentially an extra choice.

Williams applied, made it through the school’s lottery and, in the spring, received her acceptance email. “When I saw my name on there, I got kind of excited,” she said. “Everyone here I feel like has a great potential, and I’m kind of a believer in fate.”

And just like that, another Chicago high school student entered a charter school instead of a neighborhood school, chalking up another gain for the privately run but publicly funded schools in the ongoing tug-of-war to find and retain students.

Chicago Public Schools over the past decade has lost over 54,100 students, more than a 10% decline — due to the city’s shrinking population, declining birth rates, and slowing immigration. In the same period, Chicago’s charters have enrolled an additional 14,000 students, a 38% increase, in part by adding upward of 20 campuses.

Chalkbeat examined 10 years of enrollment data for the city’s charter campuses, not including options and alternative schools that serve students outside of traditional grade structures, and found that charters have grown as a percentage of the district’s portfolio. This school year, charters are educating 14% of the district’s 355,000 students, down from 15% five years ago but still larger than 9% a decade ago, according to district data. But the pace of growth has trended downward since 2015.

Even as the political enthusiasm for charters in Chicago has wound down, some schools are still finding ways to grow in a no-grow environment. They have turned to a mix of intensive recruitment, targeted new programs and, in some cases, finding authorizers outside of the Chicago school district altogether.

For 10 years, district policy, particularly driven by Mayor Richard M. Daley’s Renaissance 2010 initiative to open 100 new schools in place of struggling ones, fueled this growth. Charter backers say their schools offer an alternative to failing district schools. Critics, however, argue that charters siphon students and state money from district-run schools, which they say then must struggle harder to survive.

In recent years the political winds have shifted against charter schools. Both Illinois’ new governor and Chicago’s new mayor ran on charter-skeptical platforms. Facing language in the teachers contract that caps charter growth and grappling with districtwide declining enrollment and budget crises, more charter schools are closing than are opening this school year.

Charters face more barriers across the nation. California, New York City, and Alabama all have limited charters, forcing the industry to scramble for workarounds.

“We need to start fighting back against the attacks far more aggressively,” National Alliance for Public Charter Schools President Nina Rees said last summer.

Williams is attending one school that has bucked this trend. Nestled on the fourth floor of a building in the heart of Chicago’s Loop, Intrinsic’s new downtown campus opened its doors to its first freshman class this school year.

It almost didn’t. For Intrinsic, a network specializing in personalized learning and boasting a roster of big-name charter donors, opening the doors of a second campus wasn’t a bygone conclusion.

***

This time last year, the idea was fighting for its life. After failing to win approval from the Chicago Board of Education to open a second high school, the Intrinsic charter network — which already operated a 1,025-student high school in an imposing slate-gray building tucked amid bungalows in Belmont-Cragin — turned to the Illinois State Charter Commission. Intrinsic won its appeal, just befoe the state abolished the commission. (Beginning this summer, the state board will take over most of the responsibilities of the charter commission, but will not hear appeals for new charter schools rejected by their local districts.)

The new Loop school is serving 90 freshmen this year, with plans to expand to a second floor and more than triple the number of students next year.

“It’s important that this school, this downtown campus specifically, exists,” founder Melissa Zaikos, a former network chief in Chicago Public Schools with an MBA from Harvard Business School, told Chalkbeat. The school offers a high-quality and physically central alternative for students who may not have access to those, she said.

Zaikos said Intrinsic Downtown places students near community college and job opportunities that may not be available in their neighborhoods. “What we’re really trying to do is provide students both the academic preparation but also the sort of social capital required to make it through whatever their post-secondary plan is.”

Traditionally, charter schools in Chicago grew by applying to the district to expand their charter agreement or to open new campuses. Schools benefited from a welcoming environment for new networks, buoyed by philanthropy and broad support from both former mayor Rahm Emanuel and his predecessor, Richard J. Daley.

Zaikos saw promise in the flexibility offered by charter schools to use a more data-centered approach. She was also frustrated by the constantly changing policy directives coming from the five CEOs that helmed the school district in the decade-plus she was with the district.

Zaikos, in partnership with Tim Ligue, a former district network leader with an MBA from the University of Chicago, decided to try their hand at opening a school. The first Intrinsic opened its doors, with a plan to serve seventh to 12th grades, in 2013.

“The idea of having a legal agreement that independently allowed us all the freedom to create a school that we knew wouldn’t change was the intention of starting a charter,” Zaikos said.

This school year Intrinsic’s original school has more than 1,000 students, of whom the majority are Latino and 87% are considered low income. The school has a Level 1 rating.

For the second year in a row, the Chicago school board has not approved any new charter applications, and the requests have mostly dried up as well. This year, no new charter schools applied to open in Chicago. In 2013 by comparison, nine schools, including Intrinsic, submitted proposals to open new charter schools to the district.

Intrinsic appealed to the state charter commission, which approved Intrinsic’s new school last March.

Intrinsic drew support from a wide and varied philanthropic community, which has also helped plan a facilities expansion. Partners and investors named on Intrinsic’s website include education mainstays like the Walton Family Foundation and the Charter School Growth Fund as well as the software development company TradeHelm. (The Walton Family Foundation is also a funder of Chalkbeat.) Intrinsic also receives support from Leap Innovations, which has helped make Chicago the epicenter of personalized learning and an important frontier for some education reformers.

“The majority of the people supporting us have known us through the years,” Zaikos said. “It doesn’t feel like that’s changed.”

By offering a personalized learning model — a heavily computer-based method of learning that has some big-name adherents but little independent research backing — Intrinsic occupies a niche and can claim it offers a unique student experience.

Arianna Williams, previously unfamiliar with personalized learning, said she has appreciated being able to advance beyond her classmates in areas like math, but get extra help with subjects she struggles in, like biology.

“I feel like there’s a lot of individual work if you need it,” she said. “And being able to have that was amazing.”

On the recruitment end, the network has pulled students from the waiting list for its Belmont campus and relied heavily on word-of-mouth.

“The main source, really, is the kids we have,” said Ligue, who is now principal of the downtown campus.

“Everybody that is talking about the school has experienced the school,” Zaikos said.

Many of those testifying at the charter commission appeals hearing were parents of Intrinsic students.

“I’d like to see another school open because my daughter will be going into high school,” mother Nancy Jimenez said. “The opportunities that the school has given the children… allow the kids to thrive.”

Intrinsic can recruit from all around the city, providing a broader base of students to target than traditional neighborhood high schools that generally draw from families in their attendance zones. For Ligue, having a student body that represented the diversity of the city was essential.

“The one thing I want to be sure about downtown is we have a diverse school. I’m like, all right, what neighborhoods do we need to serve? Where are we not hitting? How can we get there?”

The network invests in building a parent community, with parent advisory committees at each campus and advisers who communicate with parents through weekly updates. Intrinsic also holds regular student-led conferences. It’s another way to ensure that generations of families will see their school as an option.

To be sure, other networks have used similar strategies to continue growing, or maintain enrollment, in an increasingly hostile climate. Noble, the city’s largest network, has a recruitment and outreach team for its 15 schools. Acero, formerly UNO, invested heavily in building connections with local lawmakers and relied on its political muscle and aggressive borrowing to fuel its growth. And Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s capital plan promised another Chicago charter school $31 million for capital improvements last summer.

Some efforts at student recruitment have run afoul of accepted practice. A new report by the district’s inspector general said one unnamed charter network improperly obtained nearly 114,000 lines of student data from a district employee, including mailing addresses, and used it for three years to try to recruit students.

But Intrinsic’s particular combination of niche program offerings, vigorous recruitment, philanthropic support, and pure hustle has contributed to its survival, and also its growth.

***

Arianna Williams enjoyed her first semester at Intrinsic’s downtown campus. Her mother was worried that going to a small, unusual school would keep her from having a “normal” high school experience.

But Williams said the school has created an engaging culture. Students took part in a contest to come up with the school’s chant, and were told they could create any type of club they want.

Zaikos and Ligue said they decided to require students to wear uniforms, to help people downtown read them as students. The school also has a strict demerit code — three infractions, which could include forgetting to bring a school ID or wear a belt, equal a detention.

That was a concern for Williams, but she has been organized enough to avoid having any detentions so far, she said.

Now, it’s about doing the work to bridge some of the divides the city creates. That includes introducing cultural touchstones like a favorite chicken joint that South Siders hold holy, to classmates from other neighborhoods. “If you’re from the North Side, you might not understand, like, leaving after school to go to Harold’s [Fried Chicken] or Uncle Remus or something like that, so I feel that there’s that kind of disconnect of meeting places.”

But just like the Loop proves to be a draw for school, it is becoming a place where students hang out.

“Everyone always ends up meeting downtown anyway,” Williams said. “We don’t hold like any petty drama.”

Catherine Henderson contributed reporting.