Illinois lags behind other states in preparing aspiring elementary teachers how to teach reading — and it isn’t improving, according to a report this week from the National Council on Teacher Quality.

The report awarded a D or F to 19 higher education programs — 43% of those the council evaluated in Illinois — on how well they prepare teachers in scientifically based reading instruction methods. The council gave 38% of the teaching programs an A or B, and 18% a C.

Nationally, more than half of traditional teacher-training programs earned an A or a B grade, up from 35% in 2013. Across the country this year, 39% of programs received a D or F score, a lower percentage than in Illinois.

“Not only does Illinois not do well, but there are no signs of improvement and that runs counter to what we’re seeing in many states,” said Kate Walsh, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality. “It’s extremely frustrating to see. Kids aren’t learning how to read and what is more damaging to your life than not learning that essential skill?”

Other states, including Colorado’s teacher preparation programs, also scored poorly in the report. Higher education officials have criticized the council’s methodology.

The study graded 44 undergraduate and graduate education programs across Illinois. It did not review 10 other programs, including the University of Chicago, that did not provide enough information about how they teach reading.

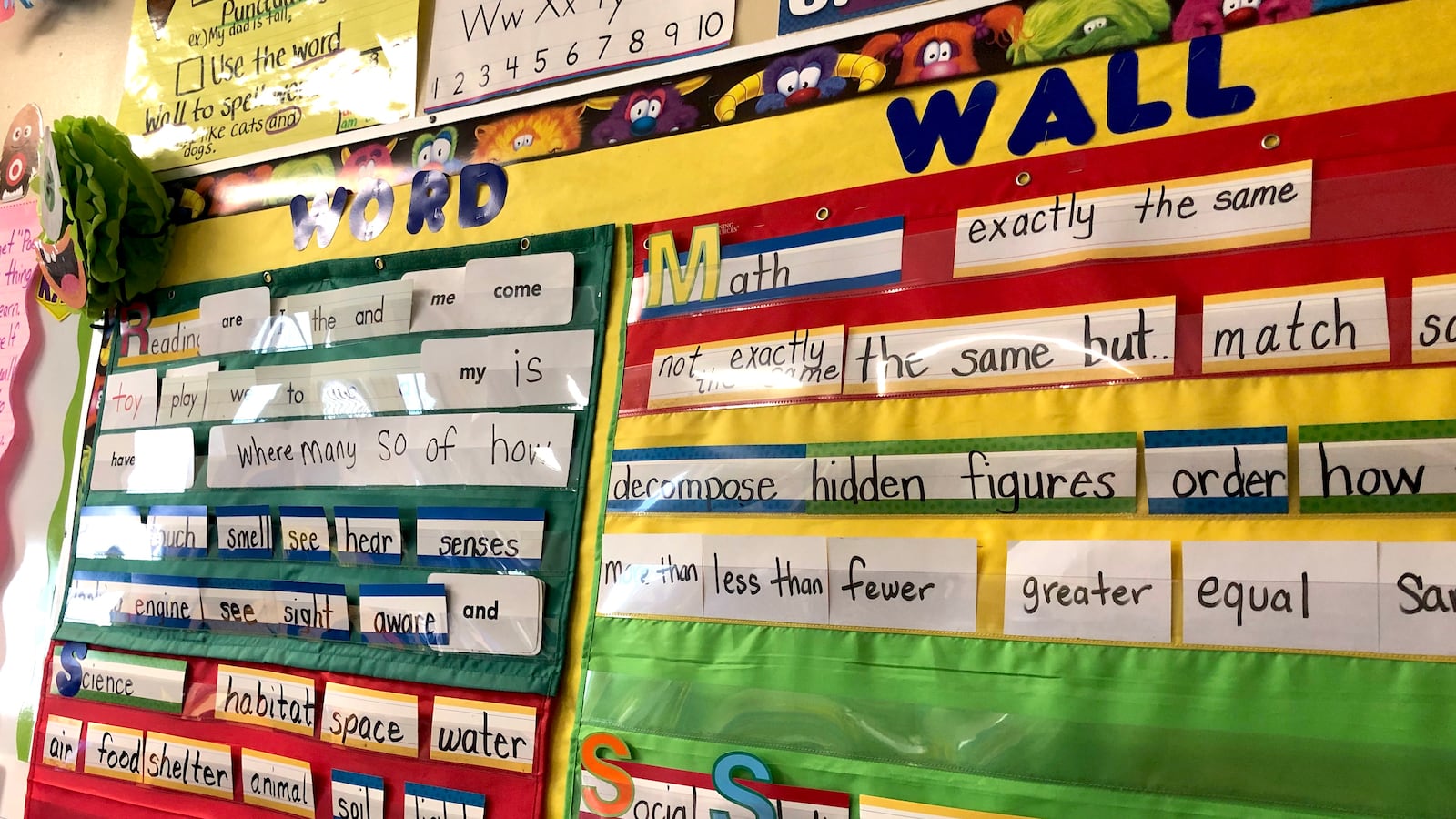

To determine the rating of each program, literacy experts review the topics, readings, assignments, practice opportunities, tests, and textbooks of required early reading courses to determine whether they effectively teach the science of reading. That method includes five components: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Walsh said that the science of reading method teaches 90% to 95% of kids to read.

The study also found that an increasing number of textbooks used in education programs reflect the science of reading.

Walsh said if the council doesn’t find the syllabus of a course clear during analysis, programs have multiple opportunities to submit additional materials and “correct courses and turn over additional materials” to improve their ratings.

Based on the findings, “there needs to be some on-the-ground work in the state,” such as programs investing in tools, including updated textbooks, to prepare teachers for success, Walsh said.

Higher education leaders have criticized the study for its methodology which they say doesn’t show the full picture.

University of St. Francis, a private university in Joliet, was assigned a D for its undergraduate education program. The university declined to provide the council access to syllabi or other materials, said John Gambro, dean of the college of education, calling the study “extremely flawed.” The D grade was based on evaluation of public materials, such as the education department website, he said.

“They draw conclusions based on information that isn’t there,” Gambro said about the council’s study. “The equivalent would be to judge a restaurant by their menu.”

Despite the failing grade, Gambro noted that St. Francis’ education programs are accredited by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education and approved by the Illinois State Board of Education. He added that the university uses the science of reading as the basis for its curriculum.

For a more accurate study, literacy experts might have spoken with faculty, observed students, and surveyed graduates, he said.

Northeastern University’s undergraduate program earned an A, but the graduate program received an F.

How Illinois prepares its teachers has been an ongoing conversation at the state level amid a teacher shortage. Last year, the state decided to jettison a basic skills test it previously required aspiring teachers to pass.

Becky Raymond, executive director of Chicago Citywide Literacy Coalition, said that the study brings attention to the dire issue of literacy in the city of Chicago. The coalition, which was founded in 2003 to improve the quality of adult literacy programs throughout the city, teaches reading to adults. A 2011 Southern Illinois University study showed that three in 10 adults in the city have low basic literacy skills.

Raymond hasn’t noticed a change in reading ability, and said that adult education programs also often struggle to find quality instructors.

“Retaining talent is an issue,” she said, adding that many other variables, in addition to teacher quality, influence a child’s educational attainment.