Nick Polyak, superintendent of a school district in a northwest suburb near O’Hare Airport, went to Springfield around five years ago to push the state legislature to allow remote learning days after a cold winter forced school closures across the state.

“We were looking for flexibility to run e-learning days in lieu of traditional cancellations,” he said. “Learning can happen anywhere and any time. You don’t have to be in a physical building to have school.”

From 2015 to 2018, Polyak’s Leyden High School District and two others in Illinois rolled out pilot e-learning programs under the state school board’s watch. Since then, districts have continued to use e-learning days. During last year’s intense storm known as the polar vortex, Butler Elementary School District 53 in Oak Brook used e-learning. Polyak’s district used an e-learning day in a non-weather related emergency, after a student was stabbed at East Leyden High School in Franklin Park.

Could what these districts learned about what works, and what doesn’t, with remote learning suddenly be relevant as Illinois contemplates curtailing classes, as coronavirus cases spread?

The state’s top educators seem to think so. Last week, the Illinois State Board of Education suggested districts start considering e-learning programs. By the start of this week, with the number of Illinois coronavirus cases climbing and a handful of schools closing because of confirmed cases or exposure to confirmed cases, the board issued a stronger statement: “ISBE is advising every school district to develop an e-learning plan in preparation for the possibility of a school closure.”

However, many Illinois districts face challenges in designing a program. The state requires that all schools running e-learning programs ensure that every student has access to computers, and running remote learning requires internet access, which nearly 10% of Illinois residents don’t have.

Then there are school districts that have used e-learning days for a couple days throughout the year, but don’t have the systems in place to handle lengthy closures.

Leyden High School District has 3,500 students, mostly Latino and 56% low-income. Every student has access to Chromebooks. During e-learning days, teachers are required to upload their lesson plans for students by 9 a.m. Students are required to check in for each class by 1 p.m. using a Google form and upload their work to the district’s learning management system, Schoology — a program students use in classrooms.

What Polyak learned during the pilot was that students needed technology and reliable internet access and the district needed a concrete plan.

“We provide wi-fi hotspots to any child that doesn’t have regular internet access at home. Not only do students have a device, but every student is connected when they are away from school,” Polyak said.

Currently, Leyden is having conversations about possibly closing the district to limit the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19. If the school closes for more than a week or so, Polyak is concerned that the district would have to redesign its e-learning plan.

“Our plan was not designed to be used long term. It was more designed for a day or two here or there. We would have to do a little bit of work thinking through sustainability,” he said.

Both Polyak and Colleen Pacatte, superintendent of Gurnee Elementary School District 56 — another participant in the state’s pilot program — are concerned about the state’s five-day limit on e-learning days.

“The question would be if there seems to be mass closings going on, how is the state of Illinois going to react to that?” Pacatte said. “If it turns out to be widespread and shuts down a lot of school systems, we don’t know what the state is going to do in response as far as requiring days to be made up,” said Pacatte, since school closures in other parts of the world are starting to span weeks.

Pacatte also is concerned about teacher pay and how to afford paying teachers to staff remote learning days and any subsequent makeup days that might spill into the summer.

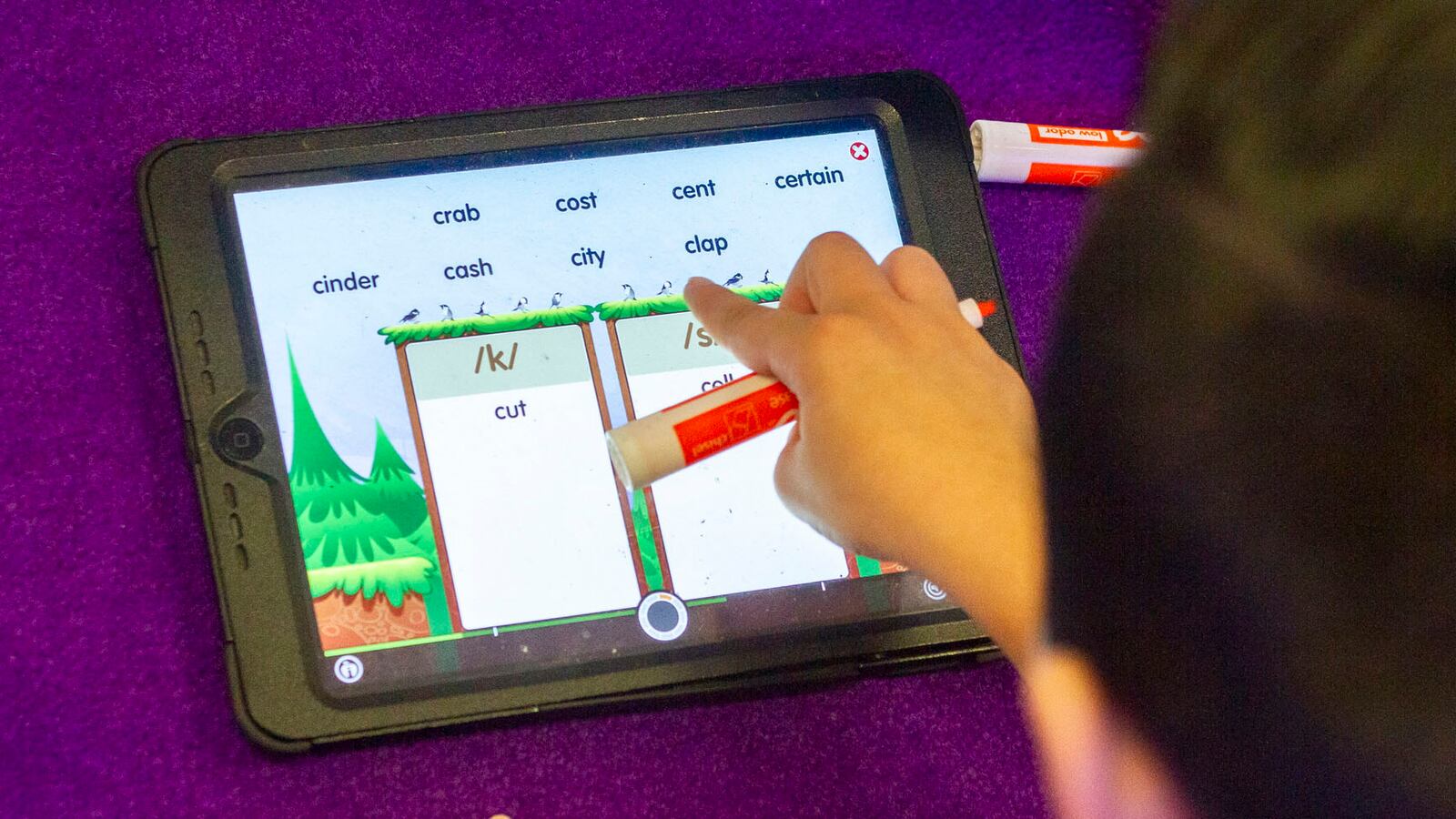

The Gurnee district serves 2,037 students and is majority Latino and 31% of the student population is low-income. Every student in Pacatte’s district has access to iPads and portable wi-fi units if needed. Teachers have their own webpages and have links to e-learning day activities attached to their websites. Students must submit completed work directly to their teacher.

Unlike Leyden’s school district full of teenagers, Pacatte has to worry about ensuring small children are taken care of during the day in case families cannot afford to miss work and cannot afford child care.

“E-learning, from my standpoint, is beneficial because we’re reaching in and checking on kids throughout the day and we’re giving them constructive things to work with while they’re home alone, possibly,” Pacatte said. “We’ve had kids reach out to teachers when they were feeling uncomfortable or afraid because they were home alone. We were able to get some support sent out to them in the form of safety checks and those kinds of things.”

The state’s school code has strict requirements for e-learning days. School boards have to adopt a resolution to utilize e-learning days in lieu of emergency days. Each district’s board of education must hold a public hearing on the school district’s initial proposal for an e-learning program or for renewal and their plan must be approved by the regional office of education.

For schools considering e-learning days in case of closure due to COVID-19, Polyak recommended that schools start immediately on their proposals and start communicating with educators.

“Partner with your teachers union and the support staff union. Involve your students and parents in the conversation because it affects everyone in the school’s community. The degree to which [school districts] can involve their stakeholders is very important,” he said.

On Monday, Loyola Academy, a private school in Wilmette, closed after a student had contact with a person who tested positive for COVID-19. The school instituted an e-learning day for students.

Meanwhile, Chicago Public Schools officials said on Tuesday that they did not have plans to close any additional schools, after a special education aide tested positive for coronavirus and forced closure of Vaughn Occupational High School. Still, schools chief Janice Jackson said her team was starting to put together an e-learning plan.