After a 2018 investigation revealed systemic failures to protect its students from sexual abuse, Chicago restricted which technology platforms teachers could use to communicate with their students.

But now that the novel coronavirus-related school closure will stretch additional weeks, possibly longer, those restrictions are being tested. Some Chicago teachers want the district to grant them the expanded technology access they say is critical to reaching students.

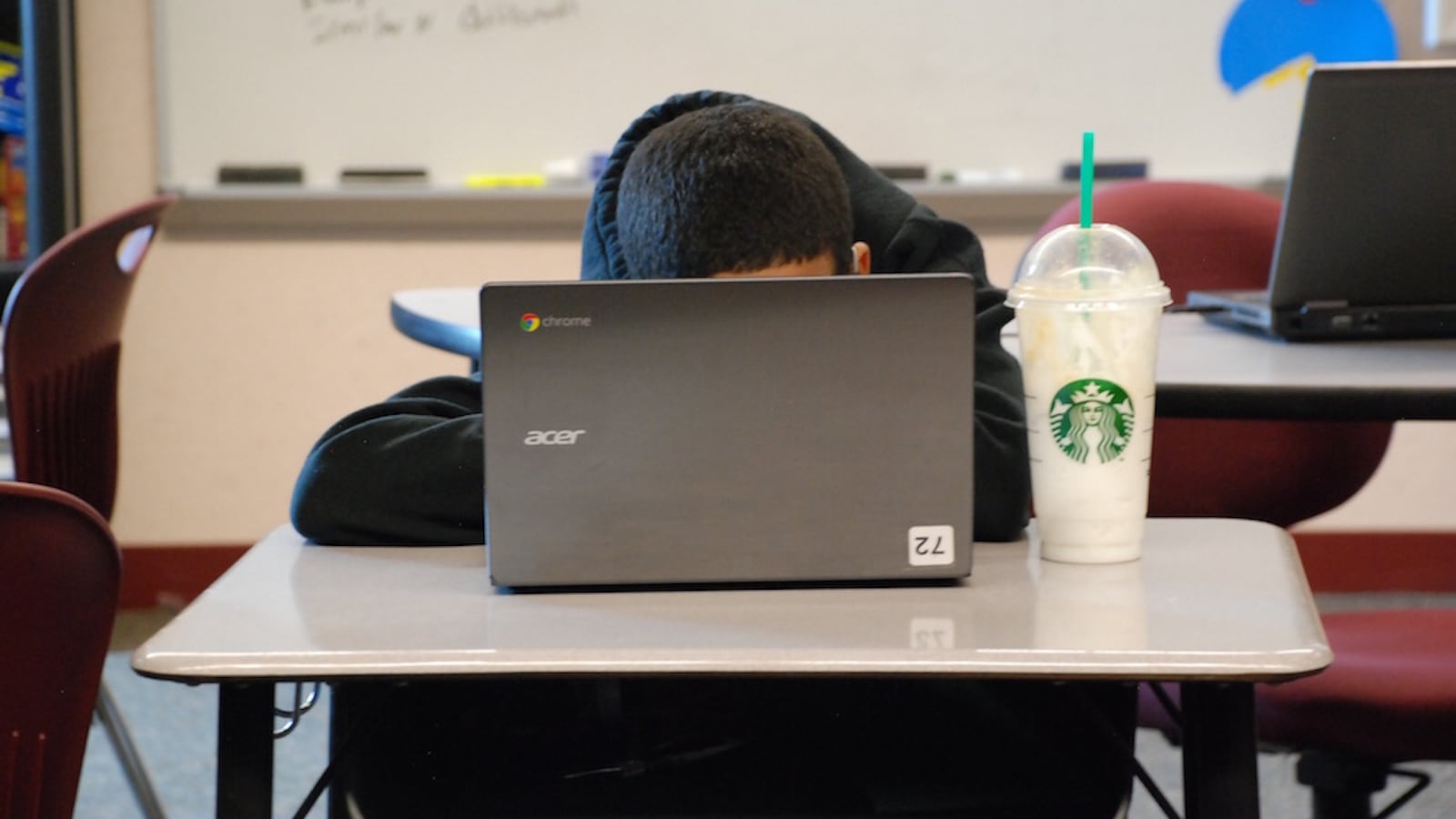

They say the need is pressing. With real-time interactions between students and teachers limited to email and text-based chatting — two-way video chats and phone calls are prohibited — their efforts to teach remotely are limited.

“I’ve been trying to find a way to interact with my students so I can help them — and it has been very difficult,” said Jeff Solin, a computer science teacher at the city’s largest public school campus, Lane Tech High School, who has taken his frustrations to Twitter. “Everything is fragmented, everyone is struggling, everyone is coming up with different resources, but so far, it’s just a way to keep kids busy with stuff.”

Their demands spotlight how the tech-based tools educators rely on — imperfect as those tools may be — have suddenly become their sole ways of communicating with students. They also spotlight how much policy goals now clash with the reality of access during quarantine. Chicago, which is under federal watch for failing to keep students safe from adult sexual abuse and has separately been criticized for its lapses in data privacy, put protections in place specifically around digital communications between teachers and students.

Protocols say students should only communicate with teachers using district-issued emails and prohibit most one-to-one communication, phone calls, and any usage of non-sanctioned communication tools — a list that includes the video platforms Zoom and Gotomeeting. The rules were put in place after the Chicago Tribune published a 2018 story that revealed systemic failures by the district to protect students from adult sexual abuse.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed everything.

Some teachers now say the new coronavirus gives the district good reason to quickly adjust its acceptable use policies for students and staff. One high school science teacher, who spoke anonymously to Chalkbeat because he feared retribution for discussing the issue, said that without two-way voice communication, it was impossible to tell if one of his students, a recent immigrant who missed the first quarter of his class, even understood a fundamental science concept he has been trying to build upon.

A district spokeswoman, Emily Bolton, said the issue is on administrators’ radar. Chicago is currently “evaluating an expanded list of approved technological resources” and it is working to make additional resources available. “We will be following up with principals, educators, and families with additional information next week,” she said.

Families, staff and students with questions can send emails to the command center at familyservices@cps.edu, she added.

Solin wants the Chicago Public Schools — the third largest system in the country and a customer of a suite of products under the banner of Google Classroom — to consider flipping the switch on Google Hangouts Meet, which teachers can use to talk to each other by video and voice streaming. Chicago Public Schools currently restricts Chicago students from using it with their district-issued emails.

He has also put forth other alternatives, such as the online video conversation platforms Go.To. Meeting or Zoom, which in recent days has lowered its restrictions on who can access its service and for how long and also allow users to record conversations and archive them so students could access them later.

“I have students who are stuck on their content from before schools closed, and I want to screenshare with them, I want to be able to talk to them, switch to an office hours or a tutoring one-on-one kind of setup,” says Solin.

But he also recognizes that no matter what he does, not every student will be reached due to access issues and limited device access in low-income homes. That problem that has crystallized for education policy makers in recent days as Chicago and other large urban districts spell out why they can’t issue districtwide e-learning policies while wealthier suburbs can.

“I realize I’m not going to be able to communicate with everyone — some of my students are caregivers in their family, some are working. I’m giving students new content to move forward on when ready and I will provide meaningful feedback on that content when appropriate; however I’m also trying to help my students catch up on material that they were struggling with before.”

The state’s mandated school closures, issued late last Friday, only gave Chicago educators about 72 hours to come up with ways to continue instruction. The district told them to focus on enrichment activities.

Sean Eichenser, who teaches English and language arts to middle school students at Smyser Elementary on the city’s Northwest Side, said he created a daily Google Calendar event — and he added a video conferencing link to it. All students have access to Google email, Google docs, the calendar, and several other tools. On Monday, the last day of schools, he showed his students how to access it and they even discussed the phone-in option for students whose only Internet-enabled device was a mobile phone.

But the district didn’t unlock student access on that particular product, so only the teacher could use video conferencing. The conversation was one way, and the chat function, which was new, did not engage students when he signed on for the first time on Tuesday, the first day of Chicago’s school closures. “Not having [a function that would allow] student response in the moment was a bummer. I’m not really interested in being a really, really boring YouTuber,” he said.

Eichenser decided to refine his approach. He kept the video link, so students still can watch him talk about “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and then he opened a Google Doc that he shared out on Google Classroom and gave students editing privileges.

The first day was a zoo. The eighth graders who logged in — about 30 of his 105 or so students — changed each other’s fonts, pasted pictures of Shrek, and deleted each other’s comments.

Eichenser said he waited and didn’t respond. Eventually, the newness wore off. “Eventually we were able to discuss Chapter 18 of To Kill a Mockingbird. The next day was completely uneventful on the doc.”

Still, he says, it’s not an ideal solution, and he would like to see the district relax its rules and allow for the full capability of Google Meet, or an equivalent video service, between students 13 or older and staff.

“I understand the concerns, I really do. But these are unprecedented times,” he said, adding that the district’s own use of social media to respond to parents and students online has impressed him.

Like Solin, he said his motivation isn’t grading or academic standards. “My biggest motivation is keeping our learning community together,” said Eichenser. “I asked them today (in the Google Doc) what music I should listen to since I can’t leave my house. They gave me a thousand suggestions.”