This week Chicago kicked off its official remote learning plan with Google Classroom meetings, teacher office hours, assignment expectations, and even grades, which are due Friday.

Prior to Monday, schools had taken an ad-hoc approach, with some schools offering assignments and others not so much.

How’s the new plan going so far? With plans largely the purview of individual schools, the experience has varied widely as everyone copes with the unprecedented upheaval and disruption. We checked in with a handful of educators and families to see what’s working so far, what needs improvement, and where they see a silver lining.

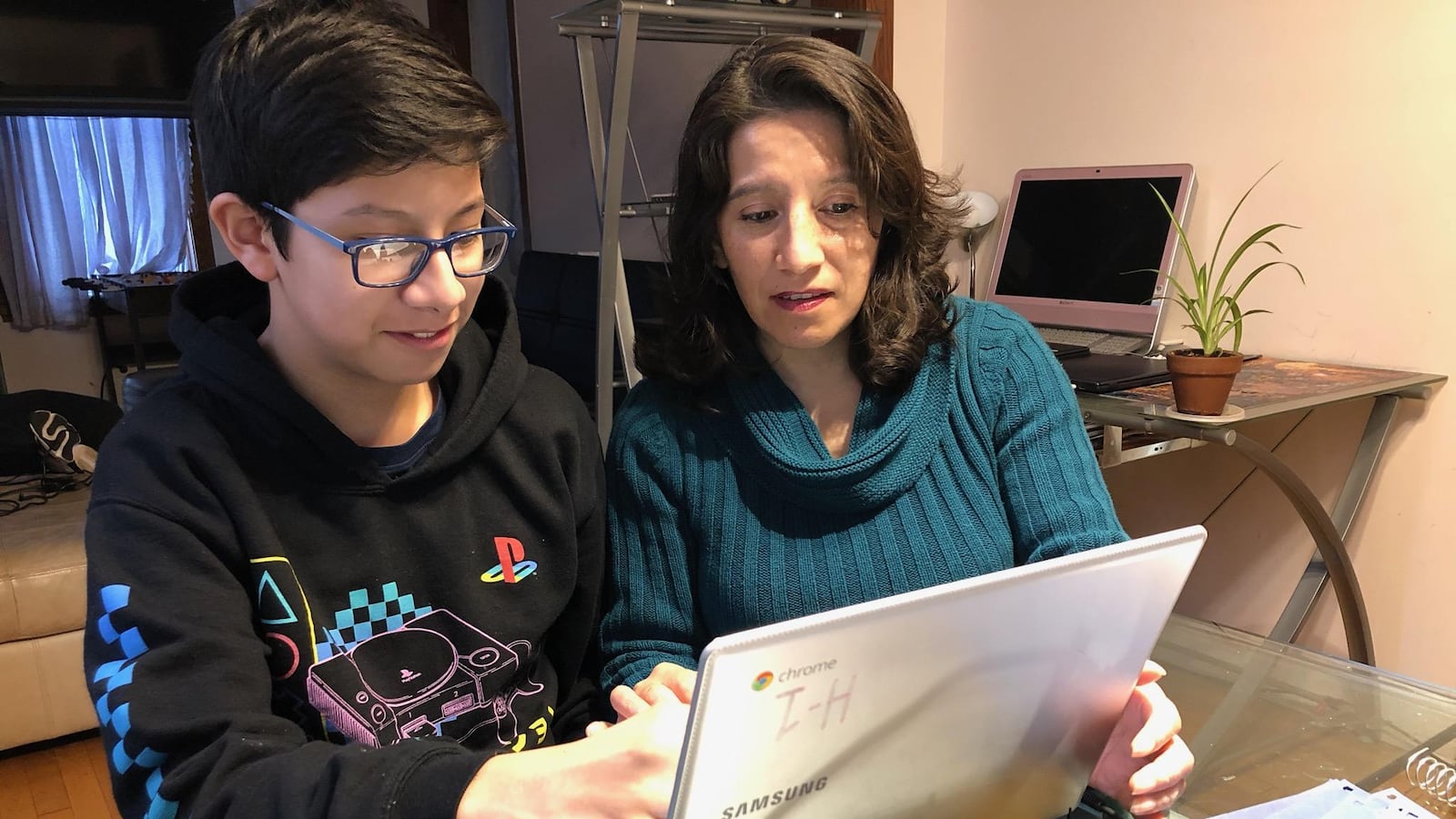

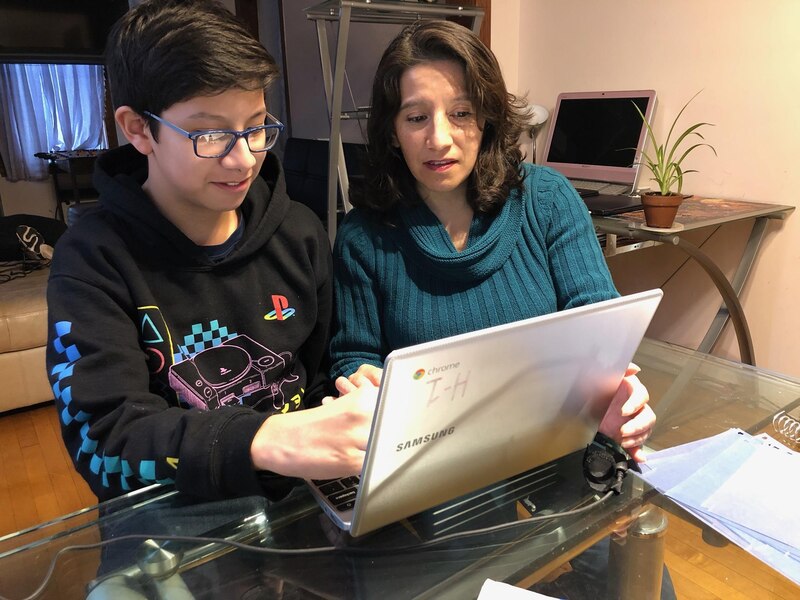

🔗Gabriela Oria, 46, parent, Madero Middle School

Remote learning got easier this week at Oria’s Little Village home, where Spanish is spoken day to day.

“I thought it would be complicated, but it’s been going well,” said Oria, a mom of two.

Oria’s daughter Jessica, a senior at the charter Muchin College Prep, helps her younger brother, Alex, with academic questions. Oria supervises the Madero Middle School seventh-grader as he adjusts to the new regimen of learning from home.

When school buildings across Illinois closed last month, Jessica’s Loop school barely seemed to miss a beat, Oria said. Muchin had a solid plan to shift learning online, and a largely self-sufficient Jessica forged ahead with her studies and college scholarship applications. One hurdle: She had to share her school-issued tablet with her brother.

Oria was determined to keep the academic momentum for Alex as well. But she says she felt daunted by the task of helping him with school work in English. It sometimes took days to hear back from teachers with questions on assignments. Once, she and Alex tried to Google the solution to a pre-algebra equation.

“Those are things I learned in Spanish, and so they are hard for me to explain,” Oria said.

Jessica added, “Before spring break, school for my brother was more like, ‘I have no idea what I’m doing.’”

But last week, the family picked up a Chromebook from Madero, part of a districtwide push to hand out 100,000 devices to students. This week brought much more structure to Alex’s school work — and ready access to his teachers, including regular office hours on Google Meet. Once again, teachers are doing the explaining, Oria says, and that’s a relief.

Oria says she would still love more guidance, in Spanish, about how to help out with school assignments. But overall, she said, “I think this is working.”

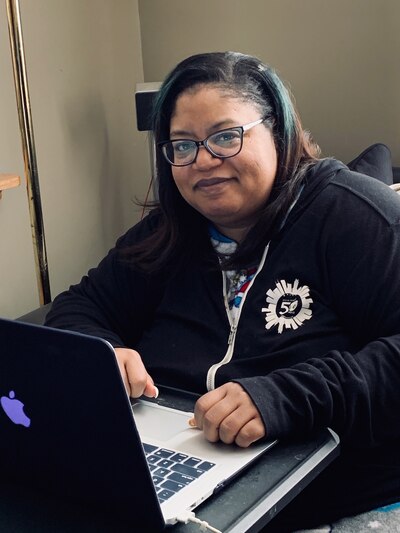

🔗Alyssa Rodriguez, 28, social worker, Rodolfo Lozano Bilingual & International Center Elementary and Wilma Rudolph Learning Center

Last week, in preparation for remote learning at Chicago schools, social worker Alyssa Rodriguez found herself putting together packets of worksheets and puzzles.

Some of the elementary and middle school students whom Rodriguez supports have cognitive needs that make it difficult to learn on screens, so Rodriguez and her classroom teacher colleagues create workarounds.

“This is hands-on learning that reinforces what we are learning in the classroom, and we will just update it weekly,” Rodriguez said. “It has been really cool to see how creative people have been.”

As a social worker assigned to two schools, Rodriguez is providing support to teachers and families as their needs arise, while creating both digital and paper lessons that offer students a break from routine, or a chance to check in on their feelings.

Two to three times a week she prepares a mental health activity for students. This week, she put together a “Wacky Wednesday” dance party, based on music from the “Trolls” film, and created videos where students can discuss how characters feel as a way to work on processing emotions.

“It’s about being creative and supportive and being ready to take on every kind of social-emotional wellness aspect that you can,” said Rodriguez, who has herself bought new houseplants to spruce up her home space during the significant increase in stay-at-home time.

The activities also have brought Rodriguez back to the roots of social work — not only helping students where their needs arise in schools, but assisting with broader requests.

She has helped families apply for unemployment benefits, and secure food and diapers.

Overall, Rodriguez said, this moment feels like an important time to be an educator.

“I really do think, at like a school level, every teacher and educator is giving their all,” she said. “I can say that I have never been prouder to be an educator.”

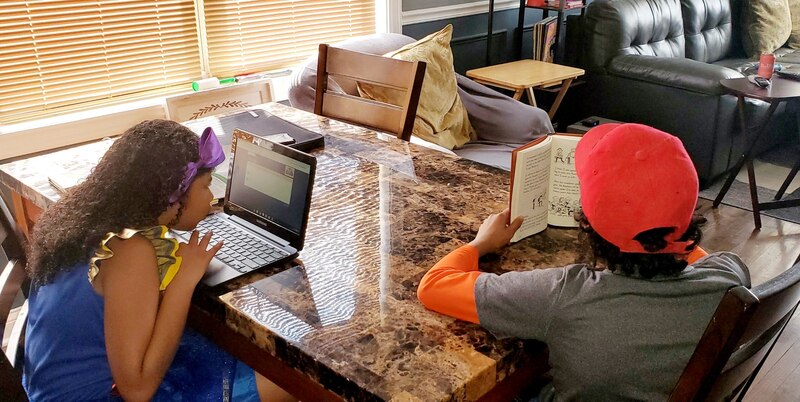

🔗Jody Acevedo, parent, children attend Nathan Hale Elementary and John F. Kennedy High School

For Jody Acevedo’s three children, remote learning was initially marked by fits and starts, and stress, as she juggled overseeing homework with her job as a TSA payroll scheduler. She’s temporarily able to work from home, but her job often requires 10-hour days.

“There is a whole different dynamic we’ve had to create here,” said Acevedo, whose husband works at a hospital. “I have to figure out a schedule, figure out which child to help, and it’s really hard to get on a routine.”

The routine changed on Monday. Acevedo picked up loaner Chromebooks for her 10- and 11-year-olds — a big assist, since the family had been sharing devices before. But the new remote learning push brought a slew of fresh passwords, sign-on links, hiccups, even dead ends. Some teachers have responded quickly to help troubleshoot; others haven’t.

“My son had one meeting and we couldn’t get in. We clicked on a Google Meet link, and it just kept going round and round and sending me back to his login,” Acevedo said.

Acevedo’s concerns now are twofold. She’s worried about her daughter, who has dysgraphia — a learning disability that affects her ability to write — and poor eyesight. The girl uses a special tool to help her read; the school didn’t send home the tool.

One teacher set up an audio function in a reading program to help her read the assigned texts, but math assignments have been beyond her reach. “They sent her home packets of math that asked her to multiply 54 times 23. She doesn’t even know how to multiply 5 times 5,” Acevedo said.

The mother is concerned, too, about a C that her high schooler received in an honors geometry class. With grades coming out Friday, the teenager isn’t sure he’s done enough to raise his grade. (Chicago policy says that grading can only improve a student’s standing, not penalize them.) They’ve emailed to ask but haven’t heard back.

What’s working? Virtual meetings at predictable times. Siblings helping each other. A math teacher who checks in with her fifth grade son often. And two athletic coaches from Kennedy who set up team meetings and who text encouraging messages about home workouts and nutrition.

“His coaches don’t want him to get out of shape. The check-ins are a good incentive,” Acevedo said.

🔗Mueze Bawany, 32, teacher, Roberto Clemente Community Academy

For Mueze Bawany, the first week of remote learning brought a mixture of heaviness and hilarity.

One student in his Tuesday live lesson on personal finance decided to multitask and play a video game, but forgot to turn off his sound. Another was heard yelling at his sibling.

“Alex, can you not try to multitask right now?”

“Oh s—, Bawany, you can see me?” came the answer.

The stories make him chuckle.

Other conversations with students this week were more difficult, with students who are worried their family won’t be able to pay rent or are watching a parent head to work at a low-paid cleaning job without sufficient protective equipment.

“My kids are different from others. They have a ton of obligations, they live in really difficult economic conditions,” Bawany said.

Two days a week, he holds a live financial literacy lesson with a quick PowerPoint, then questions and answers. Then students break into pods for discussion. Other days, he makes space for students to check in about their feelings about the big social changes.

So far this week, he’s heard from about half of the 130 students in his senior class either by email, through Google Suite or a Google Doc.

The transition hasn’t been easy. He’s been a little nervous at times, especially before his first live class, and students have said they are overwhelmed by the links and documents they are now expected to juggle.

“I’m not trying to pummel them with work right now,” he said. “This is new, and a lot of the kids are just grappling with this reality.”

But Bawany said he also recognizes the central role that school plays in offering young people a place to socialize, and learn about themselves as people, and wants to make sure he is creating opportunities for them to be themselves.

“It’s a complex, funny, and sometimes frustrating period,” he said, “but I’m loving it mainly because that’s the only way I can see the kiddos at the moment.”

🔗Marian Towns, 49, special education classroom assistant, North River Elementary School

Marian Towns is a special education classroom assistant who works in a predominantly Latino school where a majority of students are English language learners or in special education.

Towns instituted virtual office hours from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. where students can call, text or video chat with her via Google Hangouts or FaceTime. Her main concern is ensuring that all of her students receive the help they need.

“Although we’re doing Google Classroom, not being able to sit with them to help them understand what they’re learning is my concern right now. For a lot of my students, English is their second language and the learning materials are in English. Although they have Spanish translated materials, they still need to understand what they’re learning,” Towns said.

For students with Individualized Education Programs, the school instructed Towns to talk with students and parents over the phone, but she’s been having a hard time reaching parents. “During the school year, it’s always hard to find parents. Now they’re at home and we don’t know if they have the right numbers because some of them haven’t called back,” she said.

As families are picking up devices from schools, Towns’ principals have been explaining to parents how to use them and how to reach out to teachers. “If they need help they can call the school,” she said Plus, each staff member has a page on the school website. “Parents can ask questions on the website or get teacher phone numbers there.”

🔗Emily Feltes-Maslanka, principal, North-Grand High School

For Feltes-Maslanka, a two-day Chromebook distribution drive in front of her West Side school doubled as a chance to check in with her students face to face — albeit at a distance of six feet.

She peppered them with questions that ran the gamut: Had they figured out how to access school assignments and video classes through Google Meets? Did they have enough to eat at home?

“A lot of kids were saying unprompted, ‘I really miss school,’” Feltes-Maslanka said. “That was really endearing to me.”

This first week of formal remote instruction brought more structure to teaching and learning at North-Grand, along with the educator office hours the district required across the board. Some teachers “dabbled” in connecting with students via videoconferencing, to largely positive reviews from both educators and students.

Educators took on stepped-up remote learning with “passion, tenacity and grace,” Feltes-Maslanka said.

Overall, school staff engaged more than 90% of the campus’s almost 1,000 students, from responding to teacher emails to logging on to access assignments. Feltes-Maslanka and her team plan to redouble efforts to reach the remaining students next week, the start of spring quarter.

Then, on Wednesday and Thursday, North-Grand handed out more than 200 Chromebooks, with another 300 slated for distribution early next week. The school set up two lines in front of the building — one for school meals and one for the tablets — with bright tape marking six-foot intervals on the sidewalk.

“It’s been the highlight of my week seeing my students again,” Feltes-Maslanka said. “Students are making it work.”