Parents sometimes flee Denver for suburban school districts. Jennifer Aguilar goes the opposite direction.

She drives 10 miles from her Littleton home to take her 4-year-old kindergartner to Gust Elementary in southwest Denver. It’s not that she dislikes Littleton’s schools. Her fourth-grader attends an elementary school there.

But Aguilar is willing to shop around. Her two older daughters attend Bear Creek High School in Jefferson County.

The discerning mom said she hunts for the best programs for each child, even if it means driving four daughters to schools in three districts: Denver, Littleton and Jefferson County.

The draw to Gust is advanced kindergarten, a program now in its seventh year in Denver Public Schools. The program is small but growing, with demand so high this year that Denver officials created two advanced kindergarten classrooms at the Center for Early Education in southeast Denver.

The program draws families who want a faster academic pace for their children and it helps retain some who might otherwise choose private schools or other districts.

Enrollment in advanced kindergarten has nearly doubled since its inception in 2004 when 111 children started in classes at four city schools, and nearly 50 children are on waiting lists.

459 applications, only 200 seats

This year, 200 students are in advanced kindergarten classrooms in eight schools throughout DPS. Another 48 children are on waiting lists, 46 of whom hoped to win spots at the Polaris Program at Ebert, Denver’s sought-after elementary school for gifted students.

Altogether, DPS received 459 applications for the 200 seats in the advanced kindergarten program this school year.

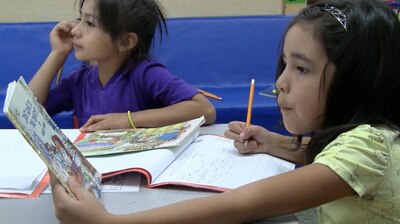

At Gust, gone are the days when kindergartners played and painted for a couple of hours. Many children arrive in Judy Pansini’s advanced kindergarten class already reading. She sends them soaring from there.

“It would be silly to review the alphabet when we already have children who are reading well,’’ Pansini said. “We see where they are and we move them up.”

By the end of the year, Pansini’s students could be reading at second-grade levels, writing their own short chapter books and doing complex addition and subtraction. Pansini remains flexible, seeking ways to stimulate each child’s individual talents.

“If I have some who are advanced in math, we can just send them to first grade for math,” she said.

Pansini’s room also boasts a Promethean smart board, a high-tech interactive device unusual in kindergarten. As the children arrive in the morning, they take their own attendance, finding and dragging their names on the large white board to show they’re ready to learn. Later, they use the board to practice letter formation, reading and math skills.

‘The kids are moving right along’

“I think it’s great,’’ said Aguilar, the mom who drives so far. “The kids are moving right along. They should be able to excel. They shouldn’t be held back for kids who don’t get it. Everybody’s different. It’s good they are accommodating these kids.”

Aguilar said her oldest two daughters, now 14 and 16, attended DPS schools when they were little and didn’t have the same option to excel that their sister, Anna, is getting. The older girls were sometimes bored in classes where struggling children demanded the most attention.

The mom raves about Pansini and the other teachers at Gust. She plans to keep driving Anna to Gust as long as she’s “excelling, enjoying herself and the teachers are on the ball.”

“We run all over the place but it’s worth it,’’ Aguilar said.

So far, data shows that children who attended advanced kindergarten scored better on end-of-the-year literacy tests than children who attended other DPS kindergarten programs. Those results applied to both low-income children and those from more affluent families.

This might be expected, since getting into DPS’ advanced kindergarten program is based on a child’s early exposure to reading and math skills.

But district data also shows that, as they progress through elementary school, the advanced kindergarten children seem to retain their advanced abilities. The second-highest achieving group of kindergartners over time were those who attended full-day tuition-based programs, where children from families who can afford to pay for kindergarten are mixed with those who need subsidies.

DPS data shows:

- Of children who started in advanced kindergarten in 2004, 98 percent were reading at or above targeted levels by the end of kindergarten. By the third grade, 94 percent of the advanced kindergarten alums still in DPS tested proficient or advanced on state reading exams.

- Among the children in advanced kindergarten in both 2004-05 and 2005-06, 179 stayed in DPS through grade 3. Of those, 25 percent qualified for federal lunch aid, an indicator of poverty. On state reading tests, 89 percent of those in poverty were reading at grade level compared to 96 percent of students from more affluent families.

- That 7-point gap by income among advanced kindergarten alums was smaller than the income gap for those attending other kindergarten programs. Among children who attended traditional full-day kindergarten in 2004-05 and 2005-06, 53 percent were reading at grade level in grade 3 compared to 88 percent from more affluent families.

- Children in advanced and traditional full-day kindergarten programs tend to stay in DPS. Between 88 and 89 percent of those students stuck with the district for first grade – by grade 5, 66 percent of advanced kindergarten and 65 percent of full-day kindergarten students were still in DPS.

DPS started the advanced kindergarten program because parents asked for it, said Barbara Neyrinck, program manager for DPS’ Gifted and Talented (GT) Department.

“Parents needed something more. The district felt that there were enough students to create a program where they didn’t have to repeat material they already knew,” Neyrinck said. “Originally, one was placed in each part of the city. We started with four classrooms and, very soon, expanded.”

Transitioning from advanced K

The program works especially well when children can funnel into advanced elementary school programs after kindergarten, such as International Baccalaureate and GT. Some of the schools with advanced kindergarten also have GT programs, including Archuleta, Edison, Gust and Polaris.

At Gust, Principal Jamie Roybal said the advanced kindergarten stimulates children and draws families to her school.

“It’s been phenomenal for us,” Roybal said. “It brings families who otherwise might not look at Gust. They come and visit and I’m always thrilled to see the surprise on their faces. They’re impressed with the programs we have. These are parents we would otherwise lose. We’re nestled up against Jefferson County, Englewood and Sheridan. So families have a lot of choices.”

State education funding follows the student so Roybal can accept children from outside Denver as long as they qualify. Denver residents receive priority.

“I’ve been thrilled because so many of our advanced kindergarten families are staying with us,” Roybal said. “They fit into our community and most go on to the GT magnet program.”

Gust has four kindergartens. One caters to Spanish-speaking children, one is advanced and the other two are traditional.

The advanced kindergarten children had homework over the summer and returned to school in August with completed packets. Those high expectations continue throughout the school year.

“It’s faster-paced, more in-depth. The students are able to read and write. They’re more focused. They have a little bit better idea of what it means to be a student. They’re reading and are eager to learn,” Roybal said. “They’re curious and have questions, questions, questions.”

She said her advanced kids start at least a year ahead. She’s tracking them to make sure that boost stays true through grade 5.

‘Advanced’ does not always mean ‘gifted’

For parents, the difference between DPS’ advanced kindergarten and gifted and talented programs can be confusing.

Entrance into advanced kindergarten does not guarantee that a child will qualify for the district’s GT program. The tests for advanced kindergarten measure what a child already knows about vocabulary, reading and math while GT tests assess a child’s potential to learn.

Neyrinck said about 60 percent of advanced kindergarten children qualify for GT each year.

At Polaris, students who qualify for the single advanced kindergarten class get to stay at the school all the way through grade 5, even if they never qualify for GT. Many parents clamor to get their children into the Polaris program since it’s one of the top-rated schools in Denver. That desire has boosted demand for advanced kindergarten testing dramatically.

Some parents choose advanced kindergarten programs at schools without GT programs and find that they’ve run into a dead end at the end of kindergarten. Families at Bill Roberts, Palmer and Stedman sometimes stay at their schools. Others, along with the parents from the Center for Early Education, have to spend their child’s kindergarten year strategizing about first-grade options.

“We always encourage parents to apply to both (regular choice programs and gifted programs),’’ Neyrinck said. “Finding the right school is a big shopping expedition. DPS has always prided itself on having options for students at the top. (Advanced) students need teachers who can challenge them and peers who understand them.”

She said DPS is in the midst of evaluating demand and capacity for various programs and may need to create more advanced offerings in future years.

Advanced kindergarten seems to be generating results at a low cost. The program is no more expensive than traditional kindergarten.

“It all has to do with the district being nimble and adapting to changing needs in the world,” said Cheryl Caldwell, DPS Director of Early Education, who has been studying advanced kindergarten and student outcomes over time.

“We’re looking at the exact needs of special populations regardless of whether they are at the high or low end and figuring out if we have programs to meet those needs.”