Legislators face tough decisions next session about whether to cover the loss of local tax revenues or force school districts to eat those cuts.

That was the key message for school districts out of revenue forecasts and economic reports given to the Legislative Council, Joint Budget Committee and other legislators today by legislative and executive branch economists.

While they said the national and state economies continue to improve, the December revenue forecasts were little changed from those issued in September.

Lawmakers also received forecasts of 2011-12 school enrollment and local property tax collections, reports that are made only in December.

Changes in local revenues are key to the funding picture for K-12, said Todd Herreid, fiscal director of the Legislative Council staff and a school finance expert.

Those local revenues, which come from property and vehicle taxes, are projected to drop by $143 million for the 2011-12 school year. Traditionally, the state covers losses in local revenue, but the tight state budget situation makes it an open question whether lawmakers will do that for next year.

It’s widely expected that state support of schools will be no better than flat next year. What’s called “total program funding” this year is about $5.4 billion, some $3.4 billion from the state and $2 billion from local taxes. The school finance bill passed by the 2010 legislature specifies that funding would stay level for two years.

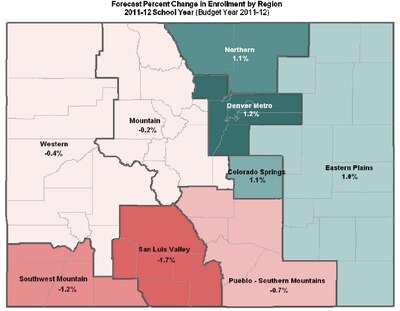

Flat funding is an effective cut for schools, because they don’t get money to cover additional costs created by enrollment growth and cost increases. The enrollment projections predict increases of just under 1 percent, about 7,000 students, in each of the next two school years.

But the drop in local revenues will force the state to come up with more money if total funding is to be kept at about $5.4 billion.

Projections cited by Herreid show the local share is expected to drop to $1.87 billion in 2011-12, forcing the state to come up with $3.56 billion to keep total funding level.

“That leaves the question where will that money be financed from,” Herreid said.

Lawmakers basically have only two places to get that money, the state’s main General Fund or the State Education Fund, which is restricted to educational uses.

The General Fund will be under pressure next year, among other reasons, because of the need to replace federal funds that helped cover Medicaid and higher education costs in the current 2010-11 budget.

The State Education Fund is used to cover some school aid and specific state education programs and has limited ability to take on additional burdens.

Herreid also said that lawmakers may have to tinker with current-year school aid because local tax collections have come in $23 million less than projected when school spending was set by lawmakers last spring.

He said lawmakers will have to figure out “how are you going to handle this $23 million?” The legislature can come up with the $23 million from somewhere in state revenues “or require school districts to take another $23 million” cutback in this school year.

Local revenues and school enrollment

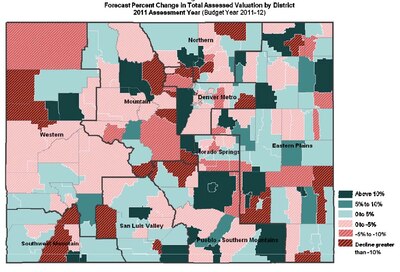

The Legislative Council report said, “Total assessed values for all property classes decreased 5.3 percent in 2010 to $92.6 billion, mostly due to the dramatic drop in oil and gas values. Assessed values are expected to decline another 6.9 percent in 2011 as a result of declining residential and commercial property values.”

Jason Schrock, a legislative staff economist, told the meeting that “The declines we’ve been hearing about are starting to show up now.” He was referring to the fact that tax assessments lag behind the actual declines in property values, so that the drop in real estates values that occurred in 2007 and 2008 are now being reflected in assessments – and will be reflected in lower school district revenues next year.

On enrollment, legislative researchers estimate K-12 student counts will increase .9 percent in 2011-12 (7,003 full-time equivalent students) and .9 percent in 2012-13 (7,439 FTE).

“Enrollment along the Front Range in the Colorado Springs, metro Denver and northern regions will experience the fastest growth,” the report said. “The Pueblo, southwest mountain and western regions will see enrollment declines,” as will the San Luis Valley and parts of the eastern plains.

(See bottom of this story for two maps showing enrollment changes by region and assessed valuation declines by district.)

The overall picture

“Our economy has already started to recover,” told Natalie Mullis, chief legislative economist, told lawmakers.

And, state revenues are growing – the Office of State Planning and Budgeting estimates that 2010-11 revenues will be 5.7 percent, about $370 million, higher than 2009-10 state income.

Yet Mullis said lawmakers may need to cover a shortfall of up to $1 billion when they craft the 2011-12 budget. That doesn’t mean current spending will have to be trimmed. It means that the cost of increased caseloads (such as schoolchildren and Medicaid patients) and federal stimulus dollars that disappear after next June 30 will have to be covered, or programs cut back, in order to end up with a balanced budget.

In November outgoing Gov. Bill Ritter submitted a balanced 2011-12 budget, but it used transfers of cash to the general fund, delays in payments and other devices to do that, along with some cuts.

Legislators may or may not go along with such ideas.

Lisa Esgar, deputy director of the Office of State Planning and Budgeting, said Monday that the Ritter plan needs further adjustments, and she expects the incoming Hickenlooper administration to submit a new budget balancing proposal by February.

Enrollment map

Valuation map

Do your homework

- Legislative Council revenue forecast (enrollment projections start on page 49; local revenue estimates begin on page 57)

- Office of State Planning and Budgeting forecast